7 de septiembre 2022

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Three young Nicaraguans transform forgotten memories of their country into digital archives, available for anyone to see on Instagram

The revolution was televised. It was also photographed. The popular uprising that toppled the Somoza dynasty in 1979 and the subsequent counterrevolutionary war against the Sandinista government in the 1980s had a magnetic effect on photojournalists from around the world. They produced unnerving photographs of a complex, turbulent and violent era of Nicaraguan history— and their images were seen around the world.

But there were countless other images that nobody ever saw. Forgotten family photographs that remained tucked away in dusty drawers and yellowed albums. Pictures that captured images of a private Nicaraguan history that —until recently — remained hidden from public view.

Now, three young Nicaraguans living abroad are proving that history never dies — even if it’s forgotten for a moment. By digging through old albums filled with family photos, letters, and postcards, they are piecing together forgotten bits of our collective history and putting them in digital archives that are available on Instagram.

Curiously enough, these digital collections of historic photographs are growing in popularity in a country that always seems to be looking towards its past for clues about the future. What started as personal photo archives have become a series of online communities of Nicaraguans who want to build a collective experience by contributing photographs of their own.

Confidencial recently spoke to these three young Nicaraguans — Gabrielle Garcia Steib, of the Instagram page Imagenes de Nicaragua; Gustavo Ayón, creator of Atlas.Chacuatl; and an Instagrammer known only as “El Desertor,” of the page eldesertor_— to find out how they are, in the words of Ayón, “reimagining Nicaragua and rescuing the untold stories.”

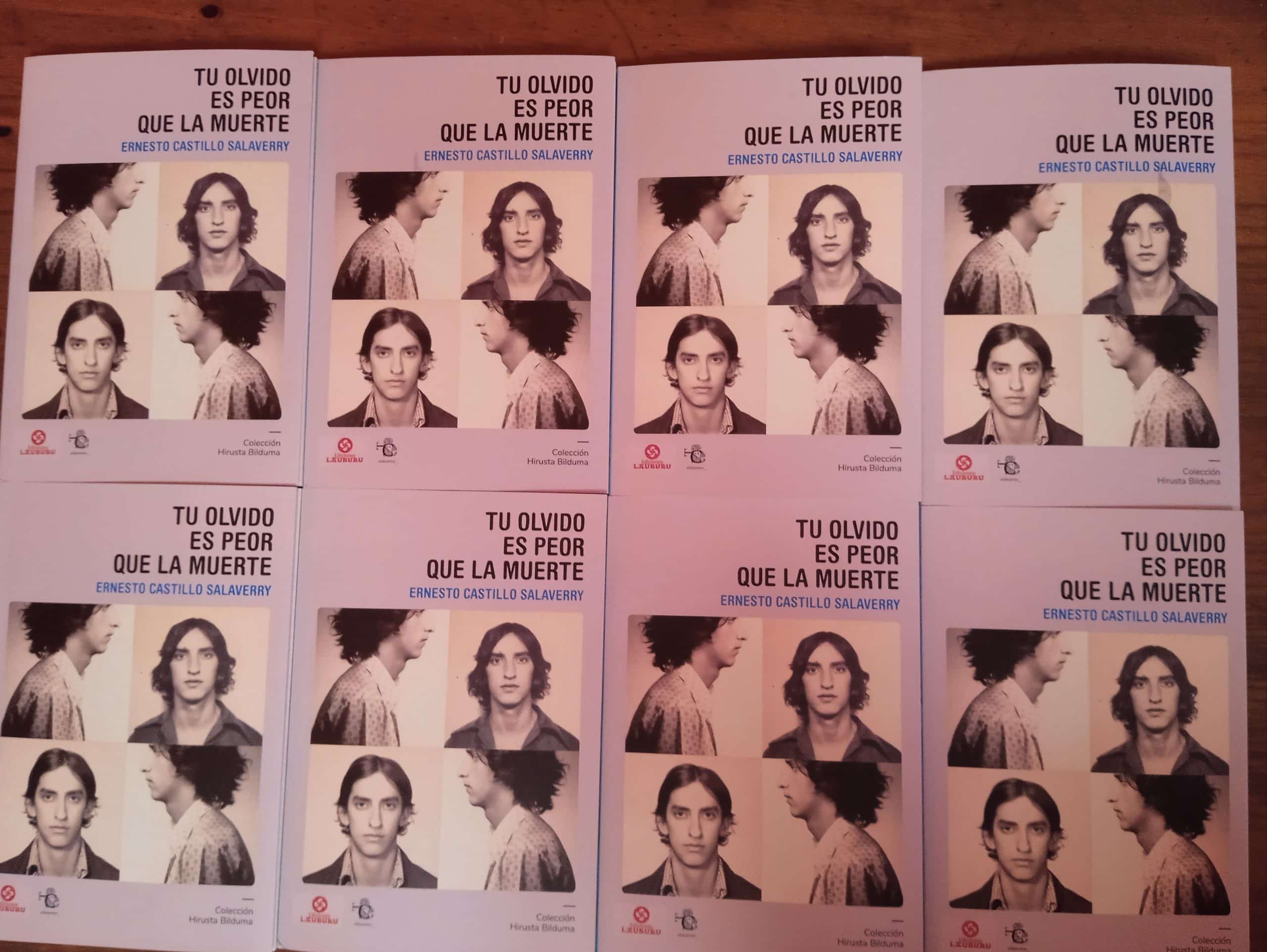

Tu olvido es peor que la muerte, a posthumous anthology of the work left by Ernesto Castillo Salaverry. Photo: Courtesy of Eldesertor_

With over 1,000 publications and much more material that he has yet to share, El Desertor’s Instagram page is an impressive collection of manuscripts, poems, and rare editions of books printed in Nicaragua.

The person behind this page, who asked to be identified only by the name of his account, which means “the deserter,” is an editor who has dedicated extensive research to find these hidden gems. In doing so, he says, he’s preserving a part of Nicaraguan history that is scattered and inaccessible to most.

“The literature of Nicaragua is kind of like a cloister. There are many things that stay within the world of writers, researchers, and academics. So the idea of El Desertor was born to share those things that are within the archives and personal collections. I wanted to give it that name to go against that cloister-like attitude of keeping this content and literature a bit secret, and above all, it’s (about) the issue of liberating it,” says the 26-year-old.

“The thing that has been wonderful for me is that certain writers have approached the page and have shared things from their personal archives with me. Daisy Zamora has sent me photos from the ministry of culture, and photos with Ernesto Cardenal, which are not photos by journalists, they are not photos from magazines. Those are photos from her family album with these figures. Many people have shared that with me. Close relatives of poets and writers, who find a photo in their family archives and have sent it to me. So that is interesting because they are not anywhere else.”

El Desertor goes beyond Instagram. The mysterious publisher also organizes online workshops and publishes books as well, including Tu olvido es peor que la muerte.

“The book is about Ernesto Castillo Salaverry, a 21-year-old man who was killed in the insurrection of Leon in 1978. He was my uncle,” El Desertor explains.

He describes the process of putting the book together as complicated. “It's looking through drawers, finding pictures, and taking something out of the past that not everyone is willing to see, for better or worse,” he says. Even so, the book was very well received in Latin America, and some of the poems that were written by his fallen uncle more than 40 years ago are still relevant today.

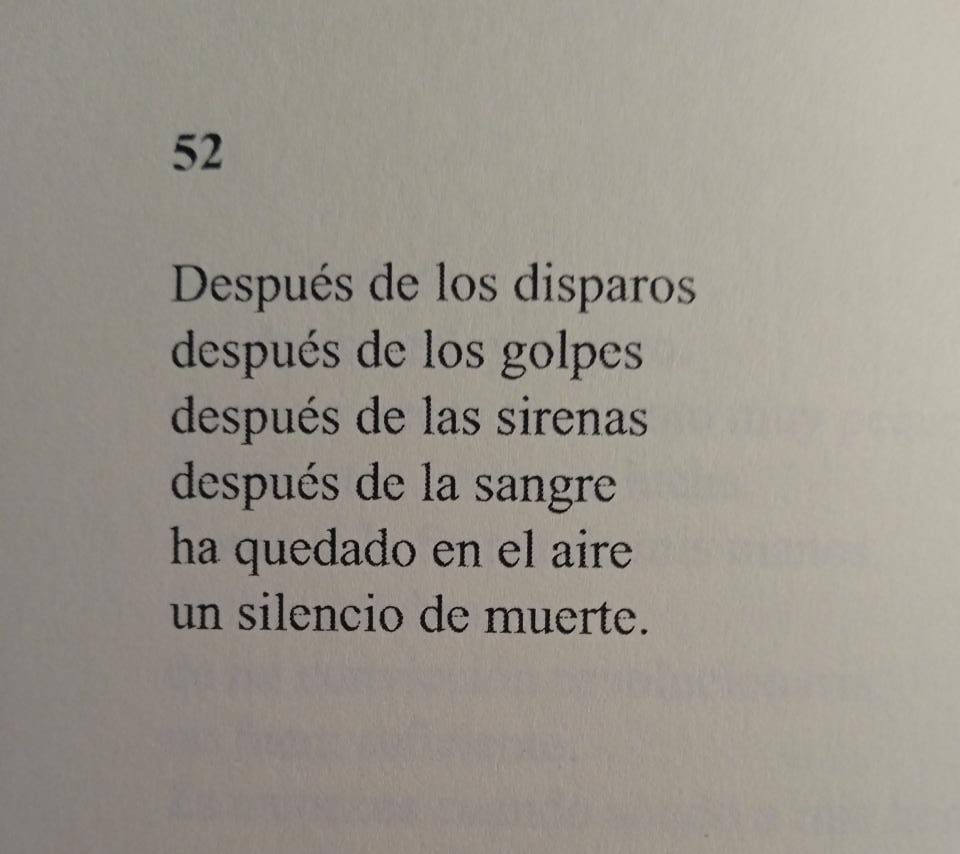

A poem written by Ernesto Castillo Salaverry more than 40 years ago. Photo: courtesy of eldesertor_

El Desertor was also inspired by his grandfather, who owned a subversive bookstore in León in the 1960s and ‘70s. When his grandfather’s collection of books was no longer enough to satisfy his curiosity, El Desertor began browsing through the Roberto Huembes market in Managua. “I started talking to the vendors who sell textbooks, bibles, but also Nicaraguan literature. It's very hidden, but there are book stalls where you can find gems. Sometimes you leave with something interesting printed in Nicaragua before the 60s,” he says.

During online workshops, he shares his knowledge of literature, and even tips on how to find hidden treasures in the chaotic environment of a Managua market. “I give people a little guide to go bargaining, what to look for, what to see,” he explains. Other people have begun dusting out their own closets at home and sending El Desertor their discoveries, making the collaboration of other people fundamental for this archive.

Gustavo Ayón is a Barcelona-based investigator and photographer, and the creator behind atlas.chacuatl. In Nicaraguan Spanish, a chacuatol is a jumble or a pile of things without order. It’s a suitable name for Gustavo’s archive, which at first glance appears to be a mix of anything that he finds interesting but actually is much deeper than that.

Ayón has spent hours doing deep dives into different archives of historical material on Nicaragua that can be found on the internet. He collects material from universities in the United States, the personal archives of different photojournalists, documentaries, and museums.

For Ayón, it’s important to highlight the stories about Nicaragua that are often overlooked or lost. “Much of the material that exists of the recent history focuses directly on the war, on the revolution, or the earthquake of 1972. There are many archives of the North American intervention,” he says.

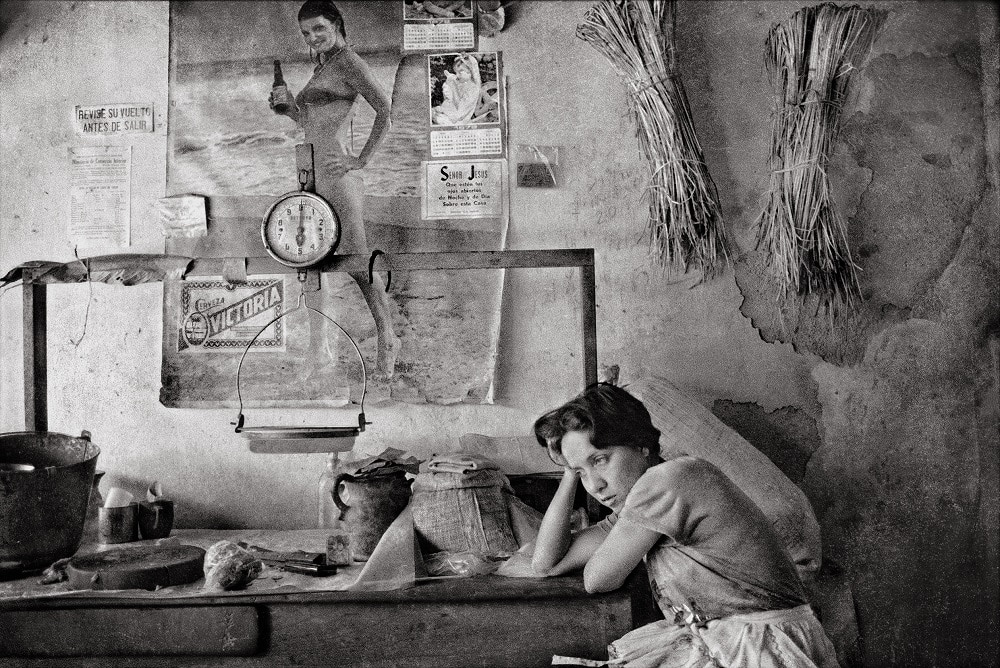

Antonio Turok "Vendedora de carne", Granada, Nicaragua, 1984. Photo: Courtesy

“[My Instagram page] searches for traces of history that have a different language, one that is not violent… not to focus on recreating the same thing that I remember about the history of Nicaragua in the war, but to take Nicaragua out of that same stereotypical vision.”

The work is in his blood. Tomás Ayón, one of his ancestors, wrote the first history book on Nicaragua, titled History of Nicaragua from the most remote times until the year 1852, at the request of Joaquín Zavala, the president at the time.

“I grew up hearing stories that have awakened me to continue believing in Nicaragua and all the things it has. Even when we are in all this mess,” Ayón said.

In the direct messages that are sent to Imagenes de Nicaragua on Instagram, people sometimes assume that either a man or a team of people is behind the page. In reality, it’s run by Gabrielle Garcia Steib, a 28-year-old artist working with archives and the moving image.

Although she was born in New Orleans, her Nicaraguan grandmother and the trips she would make to her country of origin sparked her curiosity. Eventually, it led her to investigate Nicaraguan photography and build an archive.

“In the beginning, I was just interested in seeing other photos, because I’ve only seen political photos of the war and my family's photos. I was curious to see all these other photos that I know exist,” she says.

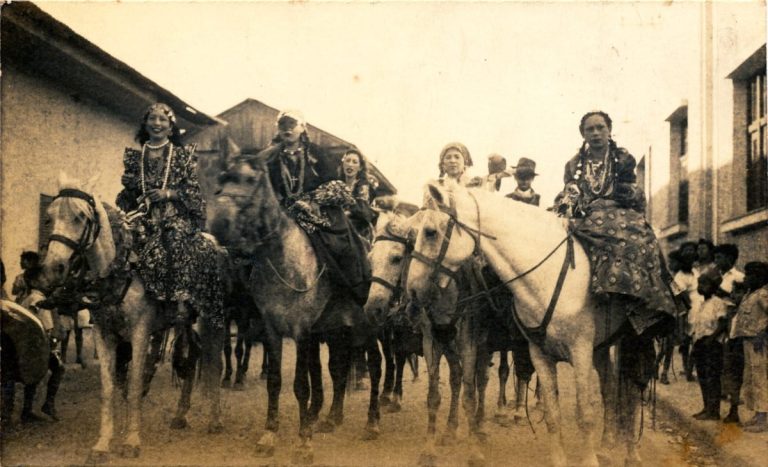

Dora Solís and Nelly Pastora Solis, grandmother and great grandmother of Gabrielle Garcia Steib. 1950s. Photo: courtesy

“I was in a constant state of investigation, in a wormhole on the internet of searching and finding more. There are so many archives here that have stuff online. I would go to the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, find a photographer, find a date, and find more”, she explains.

Soon enough, she started posting Instagram stories asking people to send in their own photos and got flooded with submissions.

For Garcia, the photos that she receives of Nicaraguan families are all intriguing and important, no matter how mundane they may appear. “I think it’s amazing that you have this photo of your grandpa in his garden, whatever. It doesn’t matter what it’s about, it’s cool to have physical, historical, and personal moments for the public to see,” she says.

The idea for the project is to make photographs from Nicaragua more accessible because there are many archives dedicated to Mexico and other Latin American countries, but few focus on Nicaragua.

“I get so many amazing messages of people feeling so proud to have something for them. It’s cool to have one (archive) specifically for Nicaraguans.”

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996. Inició como un semanario impreso y hoy es un medio de referencia regional con información, análisis, entrevistas, perfiles, reportajes e investigaciones sobre Nicaragua, informando desde el exilio por la persecución política de la dictadura de Daniel Ortega y Rosario Murillo.

PUBLICIDAD 3D