12 de mayo 2022

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

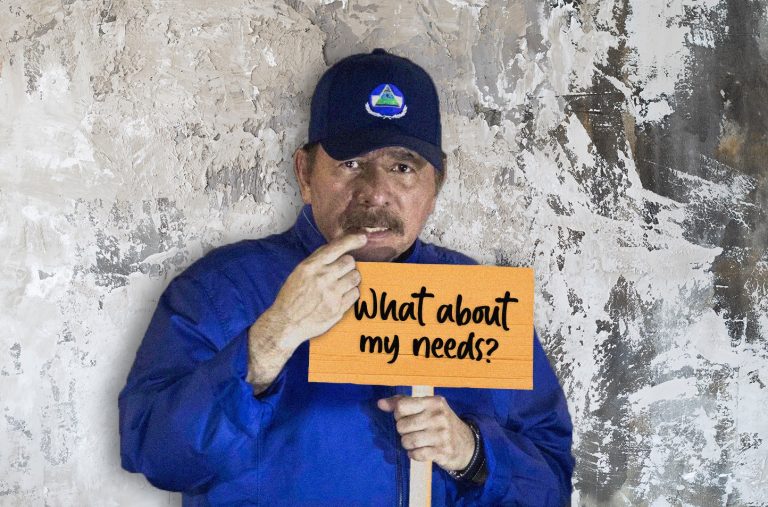

Daniel Ortega is still holding all the cards in Nicaragua. So dealing with the Nicaragua problem means asking what Daniel Ortega wants.

On most days Nicaragua seems like a problem nobody can solve.

Nicaraguans have tried for years, alternating between periods of active protest and quiet accommodation. Neither strategy has worked. Ignoring the problem only made it worse. Rising up against the problem made it much worse, much faster. Dialogue hasn’t worked. Neither has silence.

The international community has also tried a variety of tactics: engagement, disengagement, dialogue, resolutions, sanctions, threats, and isolation. So far, nothing has worked. Everything keeps getting worse.

So what’s to be done about Nicaragua?

The answer to that tragic riddle might come from asking another question: “What does Daniel Ortega want?”

It’s an uncomfortable question to even ponder. Because who cares what Ortega wants? He’s accused of crimes against humanity. He’s the architect of Nicaragua’s destruction. He’s taken so much from Nicaragua he's left the country laying facedown in a ditch with its pockets hanging out.

In a just world, Ortega shouldn’t get to ask for anything. But in the real world, Ortega is still holding all of the cards in Nicaragua. So dealing with the Nicaragua problem means asking what Ortega wants.

At least that’s the new line of thinking that's emerging among some policy experts in Washington, D.C. After years of failing to coerce the Ortega regime into changing its behavior with punitive sanctions, visa suspensions, and strongly worded resolutions, some analysts are calling for a change of tack.

The new thinking, in a nutshell, is that perhaps the promise of sanctions relief can succeed where the threat of sanctions have failed. In other words, turn the stick into a carrot.

Cynthia Arnson, a Latin America expert at the Wilson Center, says loading more individual sanctions on the Ortega regime is unlikely to “make them cry uncle.” And taking even more drastic measures to destroy Nicaragua’s economy is not going to create the conditions to get people to take to the streets in protest. Arnson points to both the experience of the contra war in the 1980s and the recent “maximum pressure campaign” against the Maduro regime in Venezuela as two examples where inflicting damage and extreme pressure failed to break the regimes' will.

A better path forward, she says, is to use sanctions relief as a bargaining chip to get some concessions. The trick, Arnson warns, is to not cash in sanctions relief as a one-off trade for the release of political prisoners, but to use the incentive as leverage to begin a process that leads to the restoration of democratic rights and civil liberties.

“I am not necessarily convinced that there is an alternative strategy to sanctions relief — and individual sanctions relief particularly — to try to produce the kinds of changes the world wants,” Arnson said this week during a panel discussion on Nicaragua hosted by the Inter-American Dialogue. “I fully recognize the dangers, and I know that this is one of the reasons why the U.S. government never negotiates in situations of hostage taking.”

However, she adds, sanctions are a means, not an end. And in the case of Nicaragua, sanctions are more effectively used as a strategic bargaining chip than a form of eternal punishment.

It’s not an easy calculation, Arnson admits. There's an uneasy trade-off between justice and impunity that’s baked into any transition from authoritarianism. But what’s the alternative?

“These are issues of almost heartbreaking debate because there is no right answer in many ways,” Arnson said. “The situation in Nicaragua is a complete tragedy.”

The goal, she said, is to help Nicaragua find a way out of the abyss. “So my question is: What does the regime want that would induce it to make the kind of concession towards respect for human rights and democratic freedoms that we all want to see in Nicaragua?”

The answer to that question, says Nicaragua expert Manuel Orozco, of the Inter-American Dialogue, is simple but impossible.

“The government wants one concession,” Orozco said. “It wants to be recognized as a legitimate government the way it is. As a dictatorship. That’s the concession that the regime wants in exchange for releasing prisoners, for improving the economy, and for reducing migration.”

For Orozco, that’s too much of an ask. “This is where you have to draw the line,” he insists.

Orozco says the Ortega regime has turned Nicaragua into a lawless “rogue state” that has “criminalized democracy” and “demoralized society” with a culture of fear. If the international community allows Ortega to get away with it, he warns, the whole Inter-American system could come off the rails.

In fact, the train is already wobbling on the tracks.

“The way the Ortega regime rules goes against humanity, dignity, and freedom — and I think the members of the Organization of American States have missed that point,” charges Orozco, who recently authored a new report, A Push for Freedom: Ensuring a Democratic Transition in Nicaragua Through International Pressure. “The OAS has reacted more strongly to the destruction of OAS property than over [political] prisoners. Nicaragua should have been suspended [from the OAS] already — they have lowered the threshold of what is the benchmark of democracy.”

Orozco is calling for “harsher penalties” against Ortega's government. He notes that cracks are forming in the regime, and says now's the time to drill down.

Orozco insists the U.S. and the international community have enough arrows in their quivers to get the job done. That starts with the U.S. RENACER Act, which gives the Biden Administration the legal tools it needs to deal with Ortega, but hasn’t been implemented full-force. Orozco says there’s also a strong argument to be made for booting Nicaragua from CAFTA, the EU Trade Association, and the OAS.

But the Wilson Center’s Arnson warns that a full-court press could backfire. “My fear is that international pressure builds cohesion in a regime,” she says. It also pushes Ortega further into the embrace of countries such as Russia, China, and Iran — although so far those relationships seem to be mostly aspirational based on shared ideology and hatred of the U.S. (see related story below).

Emily Mendrala, the State Department’s Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Western Hemisphere, says the U.S. government considers Nicaragua to be an “authoritarian family dynasty” with “no democratic mandate” in Nicaragua. She notes that the U.S. government has sanctioned 46 individuals in Ortega’s inner circle, and nine government entities.

“We view the most pressing challenges right now to be increasing authoritarianism, the closing of civic space, disregard for human rights, and the Ortega-Murillo government’s insistence on isolating and cutting themselves off from institutions in the region,” Mendrala said during the Inter-American Dialogue forum.

Also at the top of the U.S.’ priority list, Mendrala says, is “the immediate release of political prisoners held by the regime.”

How to achieve those goals, however, remains a challenge. Mendrala says the U.S. maintains an open line of communication with the Sandinista government, but adds: “The Ortega-Murillo regime has not shown a seriousness of purpose towards genuine dialogue.”

With communication limited, it places an even greater importance on "being strategic in the way we are using our diplomatic and economic tools,” Mendrala says. That means being smart about sanctions.

“Sanctions are designed to change behavior, not so much to punish,” she says.

In other words, let’s make a deal.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D