13 de agosto 2018

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

If walls could talk, what would they tell us? Graffiti collects the feelings of an era and measures the pulse of a crisis. Nicaragua is no exception

They just appear. Very rarely does anyone see who is doing them. They have no signatures. No one claims authorship. It could be dangerous to put a name to something that challenges and mocks power. When a passerby walks in front of them, they read them, observe them and even feel them. They remain in our memory, in the shape of echoes demanding justice, democracy and “a free Nicaragua.”

It’s 3:00 in the afternoon on Monday, July 23rd. A massive demonstration passes through the road to Masaya while some young people take advantage of the euphoria of the moment to paint graffiti on the walls. Grievances materialize in squiggles and phrases written with aerosols. The city is once again full of graffiti, as it was 40 years ago.

For many people who lived during the Sandinista Popular Revolution, such as journalist Sofia Montenegro, the graffiti of this new civic rebellion bear similarities with those painted against the Somoza dictatorship. This is because the social phenomenon is, in essence, “the same”: “We are facing an authoritarian and murderous dictatorial regime,” explains Montenegro.

On April 19th, a group of students from the National University of Engineering (UNI) came out to protest the of April 18 crackdown. At the entrance to the campus they wrote the first graffiti alluding to the protests. Carlos Herrera / Niu

One of the many that have appeared on the walls of Managua says: Daniel, “Que se rinda tu madre” (Fuck off, I’ll never surrender.) This was the emblematic cry of Sandinista poet and fighter Leonel Rugama, minutes before a general of the Somoza’s National Guard assassinated him. Many decades later, that defiant cry is aimed at President Daniel Ortega, the “supreme leader” of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN).

This message is written over and over again on walls and monuments of the city. The message is followed by many others as the crisis deepens, and the tone of the phrases is raised: “Murderer”, “Rapist”, “Genocidal”, “They must go!”; and others exclaim: “Long live the students”, “We are missing 300”.

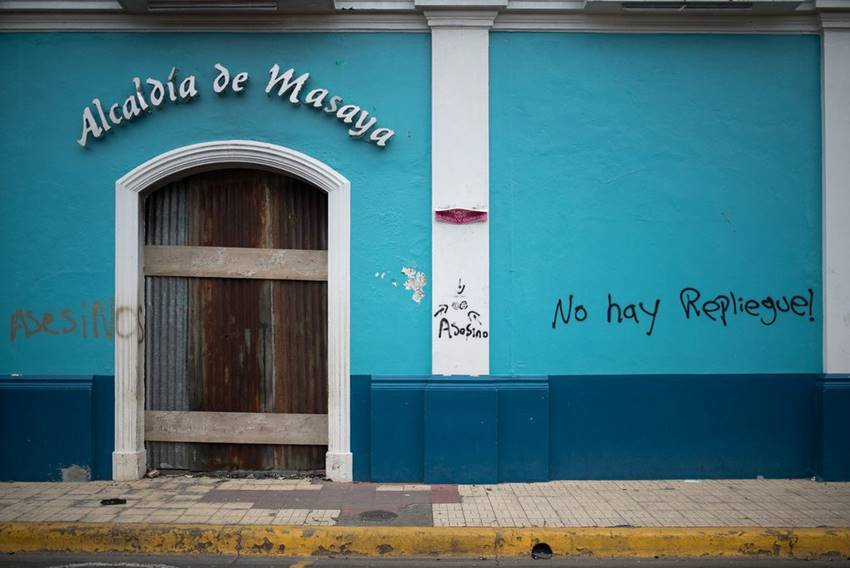

Thanks to going viral on social networks, some of these statements will remain forever, even if someone tries to erase them. One of those that caused the most impact on the internet was painted from the start of the protests in Masaya, when the entire city began to fill with barricades. On Municipal City Hall, it read: “There will be no retreat” (annual recreation of the Sandinista tactical retreat in 1979).

And so it was. What did happen is that weeks after the official date of the celebration, a convoy went to the Police Station in the city. Daniel Ortega was received by Ramon Avellan, the Police Chief, and various hooded officers. He found a city with empty streets and closed doors, as a huge big sign of disdain against the regime.

Witnesses to history-making

If walls could talk, what would they tell us? Managua is full of graffiti demanding Ortega’s departure, but how do they turn up? That’s a difficult question to answer. At the time of the Somoza dictatorship, journalist Sofia Montenegro narrates that she and a group of young people would go out at dawn to scribble the walls with contempt messages aimed at the National Guard: the armed force controlled by the Somoza dynasty that kidnapped, tortured and killed young people and opponents. But now, graffiti is done in broad daylight and more and more during the massive demonstration in the cities.

Every time there is a massive demonstration in Managua and other cities in the country, young people take advantage of the moment to write messages in public spaces. This is also done because after 6:00 in the afternoon, cities are desolated: shops close, nightlife is almost non-existent and very few walk on the sidewalks.

In this way, graffiti becomes a form of public communication, “used when the communication systems are full of noise”, states Montenegro.

“They capture the feeling of an era. That is a bit the difference in terms of not being advertisements or normal propaganda, as we could say”, added the journalist, who in her youth also made countless graffiti against the Somoza dictatorship.

They also “measure the pulse” of the population, up the ante of the conflict, and are the thermometer of how the people are feeling. Sometimes they are public statements about a specific situation. For example, historian Sofia Montenegro notes that those written in Masaya are a “categorical” message that does not admit feedback. The people have spoken, she comments. “Graffiti motivates, mobilizes, dominates, and passes through all phases.”

The graffiti war

Days after a protest, a group of workers from Managua City Hall covered up with white paint the graffiti made by demonstrators at the Ruben Dario roundabout. The following day, they inevitably reappeared.

The walls are also part of the struggle; they are a venue for controversy. For example, there is the uncontrollable governmental urge to erase them, but also the impetus of protesters to paint them as many times as necessary.

A few weeks ago, Daniel Ortega’s supporters wrote “Daniel stays” on one of the walls on the road to Masaya, but sometime later this message was modified by the “self-convoked”. The battle of the walls between protesters and government supporters depends on who writes the last word.

“That which is not named does not exists. So, for reality to exist and be recognized, walls have to name that reality. They name it by saying ‘There is a massacre here’ or ‘Ortega-Murillo are criminals’,” states journalist Sofia Montenegro.

In some departments of the country, pro-government groups indicate with painted signals the houses of persons that have participated or supported the demonstrations. Churches have also become a target for government supporters. On their walls, these groups have written “lead,” (bullets) or “coup monger” in reprisal to priests that opened the doors of their temples to receive the wounded.

* * *

While another day dawns in Managua, the workers of the Mayor’s Office finally give up. They no longer bother to reapply white paint to the walls. This time the struggle was won by the “self-convoked”.

More than 100 days since the protests started demanding that Daniel Ortega leaves power, the messages have increased in tone: “Daniel, either you go or we will kill you” was scribbled on a wall at the Colonia Centroamerica overpass. If in reality graffiti “measures the pulse” of the rebellion, this in particular shows that the entire country is far from the “normality” that the government claims.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense con tres años de trayectoria en cobertura de temas culturales y derechos humanos. Ganador del Premio Pedro Joaquín Chamorro a la Excelencia Periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D