11 de febrero 2019

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Nicolas Maduro insists on holding on to power. The question is not whether the world’s democracies should intervene, but how they should do it.

Los bienes que otros han acumulado como resultado del trabajo y el esfuerzo

Nicolas Maduro’s term as President of Venezuela expired on January 10th. Obeying the Constitution of the country, Juan Guaido, President of the National Assembly, who was democratically elected, was sworn in as interim president. Immediately, the United States, Canada and a large part of South America recognized him as the legitimate leader of Venezuela. Many European countries have done the same.

Not so Mexico, whose president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, declared that he would stick to the principle of nonintervention. Uruguay, likewise, refuses to recognize Guaido, and its ministry of foreign affairs has stated that Venezuela’s problems should be resolved peacefully by the Venezuelans themselves. Coincidentally, these two countries have announced that they will hold an international conference whose objective is to make them mediators of the Venezuelan impasse.

Their arguments are the two most often repeated by those who support the Venezuelan dictatorship. At first, they seem reasonable, but after a moment of reflection, both arguments result cynical, absurd, or both.

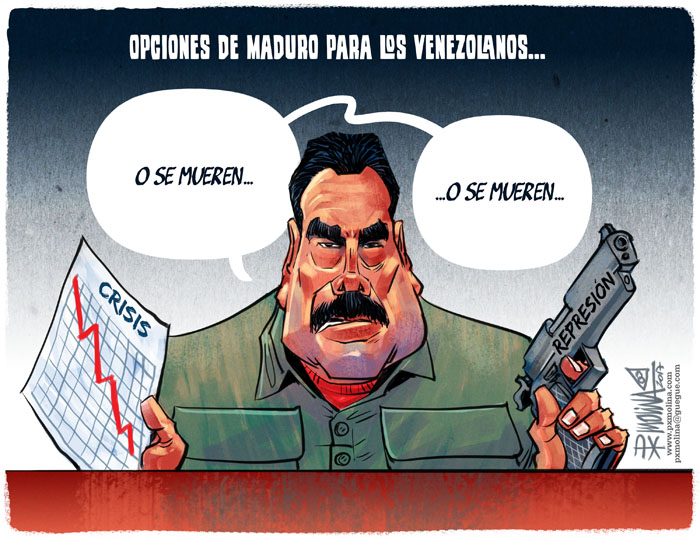

Let’s start with the second. Of course, Venezuelans should solve their own crisis. However, there is a small difficulty: Maduro does not allow them to do so.

In the days since Guaido sworn as president, the security forces have killed at least forty people and have arrested some eight hundred. In the general elections of 2015 the opposition obtained a majority in the National Assembly, but since then Maduro has stripped this body of almost all its powers and has filled the Supreme Court and the National Electoral Council with his minions.

Most of the opposition leaders are in jail or in exile, and some four million Venezuelan (one in seven) have been forced to leave their country. Human Rights Watch and other prestigious NGOs have repeatedly highlighted the systematic violation of human rights that prevails in Venezuela.

Under these circumstances, to repeat that Venezuelans must solve their own problems and then do nothing, is to guarantee that nothing will happen, except, obviously, that the rights of Venezuelans will continue to be violated. Paralysis has become a pattern. In recent years, the timid attempts at mediation by the Vatican, Spain and others, did not go anywhere precisely because that was where Maduro, reluctant to negotiate his delivery of dictatorial powers, wanted them to arrive.

That’s are the bad news. The good news is that the bold action of Guaido has motivated much of the world to action. This advance cannot be reversed now by spurious calls for nonintervention.

Dictators invariably rediscover this supposed principle when it suits them. That is what Augusto Pinochet did in Chile and Fidel Castro in Cuba. In the current case, the mantra of nonintervention also clashes with the reality that foreign powers are already intervening in Venezuela.

Cuban intelligence officials help to handle the repressive apparatus of Maduro, while China and Russia have provided loans for billions of dollars, with a not so transparent accounting that no one knows with certainty what is the fate of those funds.

The arguments for challenging the empty rhetoric of nonintervention are not merely practical. Staying on the sidelines and calling for dialogue while a thug puts a knife in the throat of a grandmother and snatches her purse, is an act that can be described as nonintervention, but it is not brave or ethical.

We have the moral duty to defend human life and dignity against atrocities, wherever they are committed. That is why most of the countries in the world (although not the United States, Russia or China) recognize the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. One cannot argue in favor of nonintervention when a dictator or caudillo commits crimes against humanity.

Advocating a supranational defense of basic political and civil rights may seem a less obvious position, but it does not make it weak. Being a respectable member of the international community entails the obligation not to lock political opponents in prison and not to steal elections.

The Inter-American Democratic Charter of the Organization of American States imposes these obligations on its signatories and includes sanctions—even the expulsion from the OAS—for repeat offenders. The sad fact that the provisions of the Charter are not always enforced (doing so requires the vote of the absolute majority of the members) does not mean that their existence is no longer ethically indispensable.

Although Maduro no longer has any legitimate right to occupy the presidency, he insists on holding on to power. The question is not whether the world’s democracies should intervene, but how they should do it. The only proof that foreign leaders should apply is clear from what Max Weber called the ethics of responsibility: What will the consequences be of my actions? Will they improve the situation?

It is conceivable that misguided interventions will worsen the situation. For example, the bellicose rhetoric of the US President Donald Trump could unleash a nationalist sentiment in Venezuela. However, skillful interventions by the world’s democracies have already had beneficial effects. Sustained political and financial pressure that raises costs for the country’s armed forces to shore up Maduro—along with a timely amnesty offer—could make a political transition inevitable.

In recent years, the international community justified its passivity by stating that the opposition was divided and that it was inconceivable that a foreign action would evict Maduro. That time is gone. It is possible that after twenty years of destruction of the democratic institutions in Venezuela and the collapse of its economy, the nightmare unleashed by Hugo Chavez and worsened resoundingly by his successor, Maduro, is finally coming to an end.

As they have done so many times throughout history, the defenders of the dictatorship will try to repress change with increasingly strident calls for nonintervention. The world should ignore them.

—–

*Andres Velasco, former candidate for the presidency and former Treasury Minister of Chile, is Dean of the School of Public Policies of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2019.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Economista, académico, consultor y político chileno. Fue ministro de Hacienda durante todo el primer gobierno de Michelle Bachelet (2006-2010). Es director de Proyectos del Grupo de Trabajo del G30 sobre América Latina y Decano de la Escuela de Políticas Públicas de la London School of Economics and Political Science. Sus textos son traducidos por Ana María Velasco.

PUBLICIDAD 3D