18 de abril 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

The return of the military is a phenomenon being seen across Latin America and the Caribbean, regardless of whether the governments are left or right

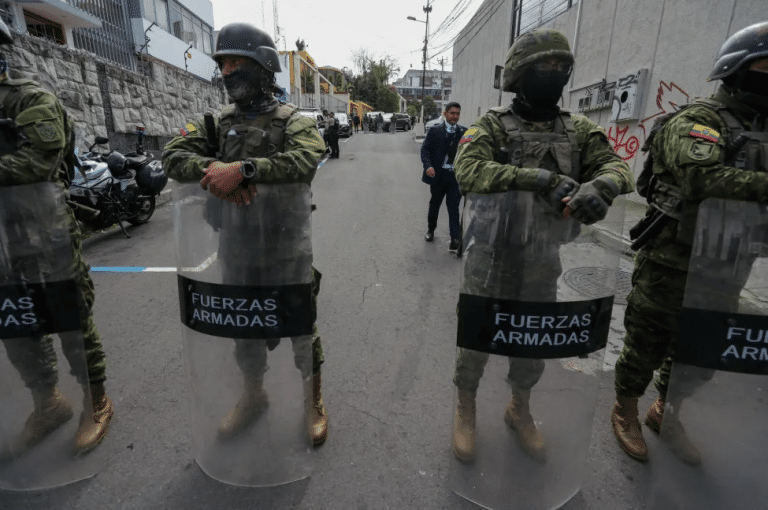

Soldiers guard the perimeter around the “Radio Canela” station in Quito, Ecuador. Photo: Jose Jacome / EFE

Thirty years ago, with the end of the military dictatorships in Latin America, the tendency towards the professionalization of the armies seemed decisive. The military institution was seen as a fundamental participant in the diverse authoritarian regimes of the Cold War. Today, the path that emerged from the democratic transitions at the end of the last century is being seriously questioned.

The two most recognizable symbols of the new right’s militarism have been Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, both – by no coincidence – viewed with similar distrust in the context of the transition narratives. More recently, the government of Javier Milei in Argentina has announced a reform in that country’s security policies to reinforce the role of the Army in the fight against drug trafficking, terrorism, the mafia, and the gangs.

Ecuador will hold a Constitutional referendum on April 21. If passed, it will introduce a militaristic focus on national security with elements similar to the Salvadoran model. The first question on the ballot asks Ecuadorans if they agree to have the Armed Forces offer back-up to the National Police in combatting organized crime.

The Ecuadoran referendum – which will take place amid intense international criticism of Ecuador’s military incursion into the Mexican Embassy in Quito – also proposes harsher sentences for the crimes of terrorism, narcotrafficking, organized crime, hired assassins, and money laundering. Ecuadoran President Daniel Noboa was among the first heads of state in the region to congratulate Nayib Bukele on his reelection, and [Bukele] has been the only one in the OAS to abstain from voting on the resolution condemning the assault on the Mexican embassy.

However, the story of Latin America’s remilitarization would be biased if we only considered the increased power of the Army under the governments of the new right. A recent book, printed in Mexico by the Grano de Sal publishing house, and entitled: Erase un pais verde olivo [“Once there was an olive green country,”], describes in detail the notable increase in the role of the Armed Forces during the administration of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador and his Morena Party in Mexico.

The authors (Juan Jesus Garza, Sergio Lopez, Javier Martín, María Marvan, Pedro Salazar and Guadalupe Salmoran) are all first line academics at the Institute for Legal Investigations of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). They document how the Law of the National Guard has allowed the military to increase its presence in the investigation and persecution of crimes in Mexico.

At the same time, they note that in the past six years 104 acts of militarization have been reported – forty more than during the past government of President Enrique Peña Nieto. In the last few years, the Army and Navy have gone on to administer civil bodies such as the airports, custom’s offices, the ports, and the immigration posts, and have taken on the oversight of large infrastructure projects such as the Banco de Bienestar, the largest disperser of funds for the Federal government’s social programs; Mexico City’s “Felipe Angeles” airport; the “Tren Maya,” a railway that traverses the Yucatan peninsula; and the inter-oceanic corridor of the Tehuantepec Isthmus.

The process of militarization in Mexico is a response to the growing challenge to government authority posed by the intense security crisis in all of Latin America and the Caribbean. The authors see precedents for the phenomenon in the populist tradition that runs between Varguismo [Brazilian followers of Getulio Vargas in the forties], and Peronismo [followers of Argentina’s Juan Domingo Peron in the same decade] plus the Venezuelan governments at the beginning of the twentieth century.

At the same time that we note the historic continuity, it’s inevitable that we also view the Mexican remilitarization in the broadest context of a regional pivot in security policies, where the new right-wing parties also sign on. The return of the military is a phenomenon across Latin America and the Caribbean, and it is advances in tandem from both the left and the right.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Historiador y ensayista cubano, residente en México. Es licenciado en Filosofía y doctor en Historia. Profesor e investigador del Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE) de la Ciudad de México y profesor visitante en las universidades de Princeton, Yale, Columbia y Austin. Es autor de más de veinte libros sobre América Latina, México y Cuba.

PUBLICIDAD 3D