11 de octubre 2022

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

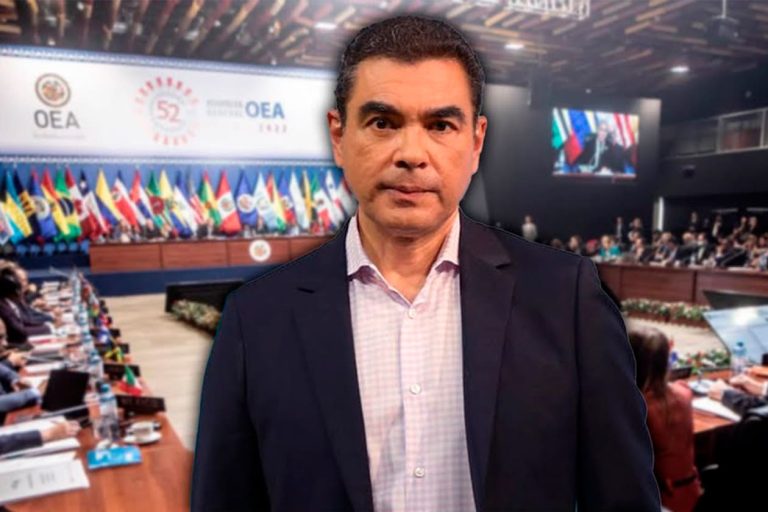

Manuel Orozco: High-Level Commission does not contemplate the “use of force”, but rather more political and economic pressure and mediation

Manuel Orozco: High-Level Commission does not contemplate the “use of force”

The unanimous approval of a resolution by all OAS countries (except Nicaragua and Venezuela, which were not present at the Assembly of Foreign Ministers) condemning the repression in Nicaragua and demanding the release of political prisoners and the restitution of democracy, represents a change in the political balance of the continent, considers political scientist Manuel Orozco, of the Inter-American Dialogue.

In an interview with Esta Semana Orozco stressed that the creation of a High-Level Commission to seek a solution to the Nicaraguan crisis, with autonomy from OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro, will have a greater scope of action over international financial organizations and bilateral sanctions against the Ortega Murillo dictatorship.

However, he warned that the mandate of this Commission does not contemplate promoting “the use of force” but rather seeks mediation that will allow a political solution to the crisis and impunity in Nicaragua.

The entire American continent's countries clearly state that the magnitude of the repression in Nicaragua is too exaggerated and there is too much impunity. What the States can do, at least, is to continue to emphasize that they are aware of what is happening and to organize themselves through this High-Level Commission (which the foreign ministers agreed upon). The other thing, which is important, is that it is clear to them that they have to do more than condemn, and at least 10 to 15 countries are working directly on implementing their own measures at the bilateral level, without eliminating the option of dialogue and mediation by the countries or the Inter-American system itself.

At least 25 countries are involved in this demand, including Paraguay, Costa Rica, the United States, and Canada. Chile has been a very active actor, a pioneer, together with Canada. But there are also other countries in Central America, in the Caribbean such as the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Trinidad, and Tobago. That is to say, there is quite a strong group for whom it is really clear that the political situation in Nicaragua must be resolved because of the consequences it has for the Nicaraguan people as well as for the entire region.

No, it is not circumstantial. These countries had already been expressing their position in relation to the situation in Nicaragua. These responses have different levels, for example, Argentina has a more critical position than Mexico. However, Mexico wants to maintain the option and openness to promote the country as a mediator in the face of a possibility of dialogue. So there is quite a lot of willingness on the part of these countries that have traditionally abstained.

The case of Honduras is because instructions came from the Presidency, it is a matter of political loyalty to Daniel Ortega on the part of Mel (Manuel) Zelaya. They had to talk about non-intervention and non-interference, but Honduras has been questioned by public opinion and by the international community about the fact that they are not really consistent with their position. Honduran foreign policy is not clear, they simply have a policy of retaliation against the secretary general (of the OAS), because he did not recognize that there was electoral fraud in the last election of Juan Orlando Hernandez, among other things. So they are in that position and Nicaragua is paying for the dirty dishes of the OAS General Secretariat.

El Salvador is assuming a rather defensive position. President (Nayib) Bukele knows that there is international pressure, the eyes of the world are on him, to the extent that he continues to monopolize and concentrate power, and the world is afraid that Central America could become four Nicaraguas and they are looking at El Salvador and Honduras as the possible Nicaraguas on the list. So, the speech that Nayib Bukele gave at the United Nations was -give me the freedom to repress, let me be free to decide who I put in jail and who I do not. I believe that this may have a solution in the short term because El Salvador also knows that it needs allies and I believe that Salvadoran public opinion is also rethinking Nayib Bukele's policies.

Colombia was clear that this resolution is incomplete, that they have the responsibility to do more and they confess that they have made the attempt and that the Government does not even return their calls. In relation to this resolution, there is a big difference, this is a commission, not a mission. What was created in 2019 was a mission with the purpose of going to Nicaragua to meet with officials of the government of Daniel Ortega and at the same time with civil society and political parties in Nicaragua at that time.

Now the role of this commission is much broader, and more discreet, in the sense that the responsibility falls exclusively on the member states, it is disassociated from the General Secretariat for strategic reasons in the sense that there is a strong alienation between the Secretary General and several OAS member countries. So, there is a broader scope given to this commission which includes not only knocking on the door but also promoting mediation, making use of good offices, but also continuing to investigate, reporting to the countries on the situation in Nicaragua, but also promoting alternative or parallel measures to mediation.

I believe that this is one of the most important objectives at this time because this opens up space for aspects related to international financial loans, the lack of accountability on those loans, as well as the complicity of some countries in this regard and also how to apply sanctions within various countries, not only on the part of the United States or Canada.

Yes, it is subject to the members of the Permanent Council of the OAS, but it is not subject to the linkage with the Secretary-General. So there is a big difference because it is the Inter-American system, but independent of the administrative governance traditionally executed in the hands of the General Secretariat and that allows it to give a more independent and autonomous scope of its relationship with Mr. (Luis) Almagro, who at this moment is in a critical situation.

There is an investigation that is being carried out at the moment on the Secretary-General, he is accused of violating ethical norms of the organization by having intimate relations with a subordinate, as has just happened recently at the IDB where the president was dismissed. What effect can this investigation and eventual separation of Almagro have on the OAS? Does it paralyze it, or does it affect in any way the way how this commission and the Nicaraguan crisis will continue to be carried out?

It really generates a lot of noise, it was not an accident or a sudden situation that the news came out days before the General Assembly and practically weeks after what is happening in the IDB, although it is something that was already known practically since 2019. The investigation has been going on for a while, the content of this investigation is unknown, the implications may lead to the resignation, to a very strong reprimand of the Secretary-General, but in practical terms, there is a political recomposition within the Member States to negotiate some kind of arrangement to maintain the activity of the OAS and independently or autonomously from its link with the Secretary-General and that, perhaps, is seen strategically as an opportunity to rescue the OAS in exchange for some kind of effect on the Secretary-General.

Nicaraguans are clear that the magnitude of the impunity that exists in Nicaragua is encyclopedic, that is, there are all kinds of repression, and anything that is not an exaggeratedly drastic activity is not enough. However, Nicaraguans have to understand that the world wants to solve the political crisis. In today's world, solutions to problems are not made by force but by cooperation, negotiation, and mediation, and, thirdly, the Ortega regime is provoking the world to use aggressive forms against the regime. They have brought the country to a situation where the proportional response they hope to have is the use of force, and the world does not want to do that and is not going to do that.

So, the member states say, we have this dilemma, we cannot act in a violent way but we need to resolve the situation of the Nicaraguans. And then there will be a series of measures that are going to be taken, economic pressure, diplomatic pressure and that will also have an impact on the internal base of the regime because, as many know, the level of weakness that exists in the regime is manifested by the dissidence that continues to grow and there are going to be signs of that.

Obviously, this regime is trying to enter into another repressive wave, to increase the level of impunity at the internal level of its base, and the international community is trying to identify solutions within that context, but Nicaraguans have to know that what the world wants is to restore confidence, and that the situation has to be resolved and that nobody has forgotten them and especially nobody has forgotten the political prisoners.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Our Staff

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D