15 de julio 2016

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

We need to engage in some sensible reflection about how to assure the rational exploitation and protection of this lake

An inhabitant of Puerto Díaz (Juigalpa) shows some fish after a day of work. Photo: Carlos Herrera | Confidencial

Last November, the Environmental Resources Management firm (ERM) contracted by the Chinese franchisee HKND completed and published their “Environmental and Social Impact Study” of the proposed Nicaraguan canal.

The documents that are still accessible show the design that the HKND consortium has conceived for the construction of this project worthy of the Pharaohs, including the excavation of a trench through the bed of the Great Lake of Nicaragua (Cocibolca). The proposed trench to be dredged will stretch some 105 kilometers (65 miles) - from the mouth of the Tule river across to the Las Lajas river - with a depth of some 30 meters and a width that varies from 300 to 500 meters, some 3-5 city blocks.

The franchise agency declares proudly: “The project would include the greatest earth-moving operation in history, since it would require the excavation of approximately 5 billion cubic meters of material (p. 104 vol. 1). As part of this, it assures us that it will excavate some 750 million cubic meters (about 18 million mining trucks, each carrying 40 tons full of rocks, sand and mud) from the bottom of Cocibolca to allow passage of the largest shipping vessels in the world, much larger than those that can currently pass through the widened Panama Canal.

The technical difficulties and environmental and social impacts that this initiative, protected under Law #840, would bring to the territory around Rivas and to the Caribbean have prompted a justifiable clamor of denunciation among the affected populations. However, besides this, the possible consequences for Lake Cocibolca, Nicaragua’s most important natural resource, warrant an objective examination of HKND’s expectations regarding the weakest and most vulnerable link in the project’s engineering.

These paragraphs then, refer solely to HKND’s absurd proposal for the disposition of the material to be dredged from the bottom of Cocibolca. I’d like to focus interest and public attention on our foreknowledge of the grave environmental, social and economic risks that such bad engineering could have on the national interests, causing irreversible damages.

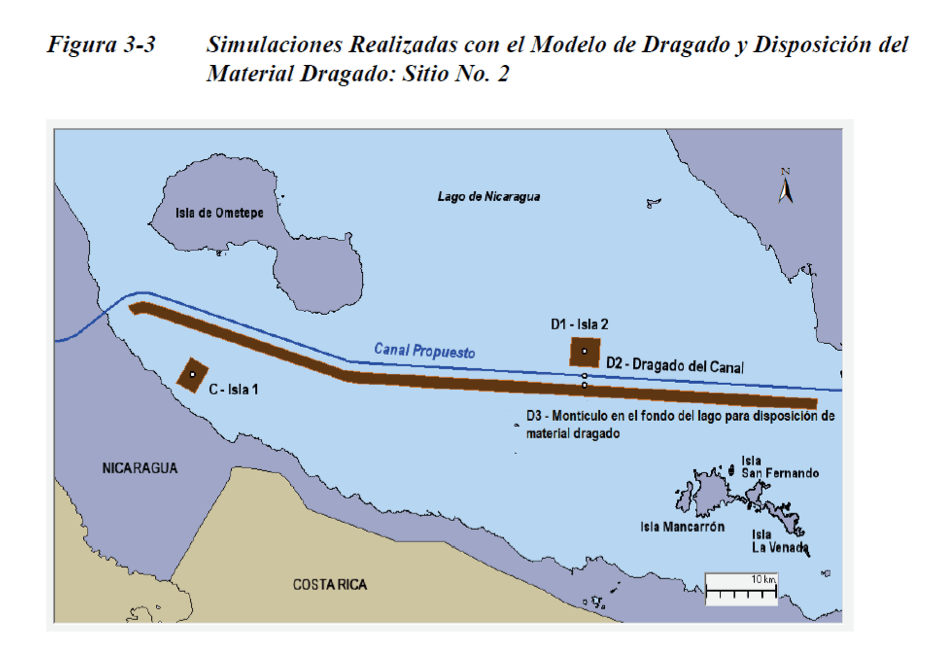

In Volume 8 of the above-noted Environmental and Social Impact Study, in the section “Effects of dredging” , we see the following figure that depicts two artificial islands in the lake as the “mound at the bottom of the lake for disposition of the dredged material” or “a non-encircled installation (LN-OW1) “ about which, surprisingly, there is no accompanying design in any of the 15 volumes of the study, no architectonic drawing or physical description of its geometry, even though it has to do with the structure of largest size (it would be visible from space) and of the greatest impact on the lake system of all the works proposed for the construction of this improbable canal.

Due to the lack of adequate projections in the design of this mound, dike or wall, its grave impact on Lake Cocibolca passes unnoticed in the recommendations that ERM presents, a fact that is inadmissible according to the International Finance Corporation’s Equator Principles, [a risk management framework established for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risk in projects]. This element alone would invalidate any governmental consideration of carrying out the project, dismissing and rejecting the initiative once and for all and leaving the idea of executing this Project definitively disqualified.

Through experience, we know that if we plant a tree and excavate a hole in the ground that is 30 centimeters in diameter and 40 cm deep, this is going to leave a mound of leftover dirt that is approximately 30 cm in diameter and 40 cm tall once the tree has been planted. The volume of the extracted earth doesn’t disappear. Perhaps you’ve noted that once a deceased person has been buried, a quantity of earth proportional to the size of the buried casket is left over - normally a hillock some 2 meters long and 60 cm high that is piled around the tomb or on top of it.

Following the same train of thought, we can then understand that by excavating the trench on the bottom of this shallow lake (whose average depth is 12 meters according to INFONAC’s 1972 bathymetric map) HKND would forcibly deposit along the length of the 105 kilometers to be excavated, a pile that is 300-500 meters wide and some 30 meters high, becoming a wall that runs parallel to the trench.

Moreover, the trench is to be located along the southern edge of the lake. Considering that Cocibolca’s depth is lowest in this area - as every fisherman or traveler to the southeast zone knows – we then see that this dike or wall would rise some 10-20 meters above the surface of the water. The purpose of placing this longitudinal mass leeward is to avoid having the enormous natural force of the constant northeast to southwest winds, responsible for the formation of lake currents (Langmuir circulation), end up returning the sediments to the trench.

This wall of China wouldn’t only divide Cocibolca in two, but due to the dynamic of the currents and the additional sediments that wash in from Costa Rica, sooner or later, the lake area between this wall and the actual southern shore of the lake would become dry land, cutting off some 40% of the lake’s area. The Cocibolca of 8,200 square kilometers that we know today would inevitably be reduced to approximately 5,000 square kms. In addition, the natural limnology of the lake (biological, chemical and physical features) would behave differently following modification of the natural patterns of circulation of the lake’s currents.

Contradictorily, the study (p. 112, Vol 1) assures that “The third zone of disposition of the dredged material is a non-encircled installation (LN-OW1). Such an installation would only receive the bulkier materials, such as sand and excavated rocks…Those materials are heavy and would sink towards the bottom of the lake, which means that their potential for affecting the turbidity would be very slight and that they would generally influence the contamination very little or not at all.”

HKND indicated that the non-encircled installation “would be found at a height of no more than 3 meters on the bottom of the lake, with the goal of avoiding interference in navigation on the lake” They then resolve to disperse the contents of 18 million truckloads – of 40 tons each – into the most sedimentary zone of the lake, equivalent to hiding the garbage under the rug, far from the public eye. That’s how they define the unauthorized change in the national geography, through which Cocibolca would be reduced to some 60% of its current area. Finally, the 38 thousand tons of sediments that daily reach this zone from Costa Rica (according to the World Bank’s 2013 study “Policy and investment priorities for reducing the environmental degradation of Lake Nicaragua’s watershed”) would cement the fatal destiny of our Great Lake Cocibolca.

Lake Cocibolca has no voice. Those of us who understand the importance of this hydrological resource for the welfare and social and economic development of Nicaragua must invite the Nicaraguan nation to engage in a sensible reflection about how to assure a rational use of it and give it the protection needed for our national hydrological security. This is a matter where we can’t risk killing the hen that lays the golden eggs.

Note: Salvador Montenegro is a member of the Nicaraguan Academy of Sciences

This article has been translated from Spanish by Havana Times.

Read the original version of this article here.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D