26 de mayo 2021

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

The regime is “hurt” by Confidencial’s resilience after the raid and occupation of its studio and newsroom in 2018. Meanwhile, it strikes at the media

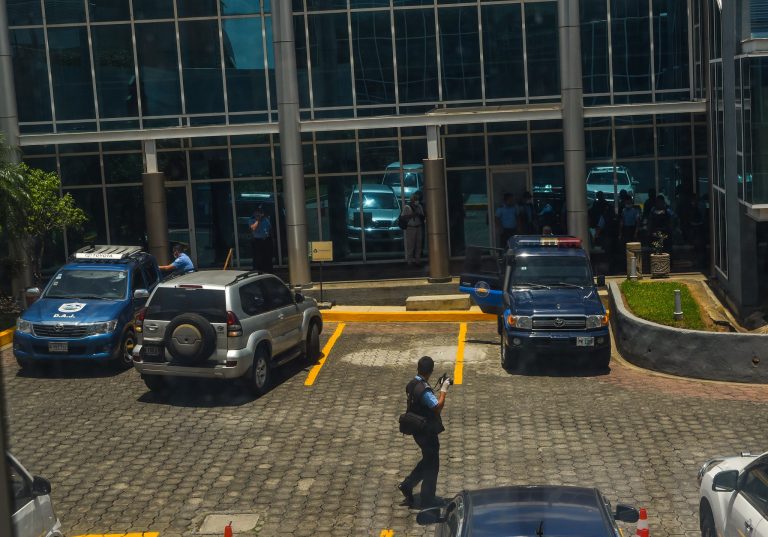

Ortega police officers remove computers and other equipment from the recording studio of Esta Semana and Esta Noche, illegally raided on May 20, 2021. Photo: Nayira Valenzuela | Confidencial

On May 20th, the Ortega Police carried out their second illegal raid against the recording studio of Esta Semana, Esta Noche and Confidencial. The assault set the tone of the new escalation of repression and criminalization against independent journalism in Nicaragua.

To fulfill their oversight function in the current electoral process, journalists must overcome the police state, threats and intimidation by the Government and its supporters.

Maria Lilly Delgado, Nicaraguan journalist and Univision correspondent, arrived to the Invercasa building to document the new blow against press freedom committed by the Police without a court order. Such was the same “modus operandi” of December 2018, when it raided, occupied and facilitated the confiscation of the building where Esta Semana, Esta Noche, Confidencial, Niú and the environmental consulting firm Cabal operated.

However, Delgado could not even get out of the vehicle when she observed police officers chasing her colleagues of the international press and holding AFP correspondent, Luis Sequeira for minutes.

“What it shows is that it is increasingly difficult for us to do our job. It sets a pattern for how difficult it is going to be for us to cover this election year,” she said in a panel of the Esta Semana program, which is broadcast online on Sunday May 23rd.

The editor-in-chief of the newspaper La Prensa, Eduardo Enríquez, said the regime is “hurt” by the resilience shown by journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro, director of Confidencial and Esta Semana and his team, after the theft and occupation of their media building in 2018. However, he said this second burglary is part of a larger plan against independent journalism that seeks to impose the narrative of the official media on the electoral process.

“I definitely believe that this is part of a plan, in greater depth against all independent journalism (…) The objective here is to see what they are plotting to do so their narrative about the elections prevails. It is vital for them to have all the independent media silenced, weakened and, if possible, shut down,” Enríquez said.

The Independent Journalists and Communicators Observatory of Nicaragua (PCIN) recorded, from mid-December 2020 to April 2021, 740 attacks against independent journalism, confirmed Christopher Mendoza, a member of the organization and a journalist from Onda Local, who also participated on the panel. Mendoza assured that journalists are also at great risk outside the capital, but attacks in the departments (like states) are often not even documented.

The uptick of violence against journalism is suffered much more during reporting. Colleagues must be attentive to police movements, paramilitaries who cover their identity with helmets, while taking photographs of them, and for Ortega fanatics, who have stolen cell phones under total impunity.

Journalism in Nicaragua has not only received abuses by the Ortega regime. The different opposition groups have also questioned the work of holding power accountable, questioning and telling the truth, without political bias. Amid a polarized context, under a de facto police state and without the consolidation of an opposition bloc to face Daniel Ortega in the elections, “the reporter has to remain as objective as possible…seeking accuracy, the truth,” Enríquez expressed.

“Our role as journalists is to point out where the faults are, to point out where the mistakes are being made.” Just as “we point out the problems to the regime, so we have to point out to the opposition everything they are doing wrong, because the final objective must be, as I told you, unity and the political solution is the unity of the opposition and work to that end,” Enriquez added.

Maria Lily Delgado said the independent media enjoy credibility among the population. “Citizens do know who they believe, and they know who is providing information with multiple versions for them to make their own judgement, professional information. They know what propaganda is,” she added. Part of this credibility is built with the verification filters to which each journalist must submit the information they receive to avoid falling into fake news,” Mendoza added.

“It was not for nothing that the regime has also created media maquilas, where it has a group of people filling the digital media outlets, filling social networks with information that misinforms the public,” he said.

The three journalists consulted conclude that despite the difficulty involved in carrying out the profession in the country, and especially the coverage of the electoral process, journalists will be there.

Enríquez believes we must go out on Election Day on November 7. It will be an “audacious act” in a possible scenario: “full with paramilitaries, full of armed motorcyclists, full of threatening riot police.” He acknowledges that it is a difficult task for reporters, but that it must be accomplished.

“We can report if the turnout is massive, or if that flow of people is simply scarce. We’ll have to see how it is interpreted, which is going to be a great challenge. We are not going to have any observation [national or international], probably any opposition poll watchers are going to be removed, if there is real opposition. And we have to report all that, present it, so that in the end, whoever follows it realizes what took place there was a real election or simply the population, in some way, rejected the regime or what really happened,” Enriquez said.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D