Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

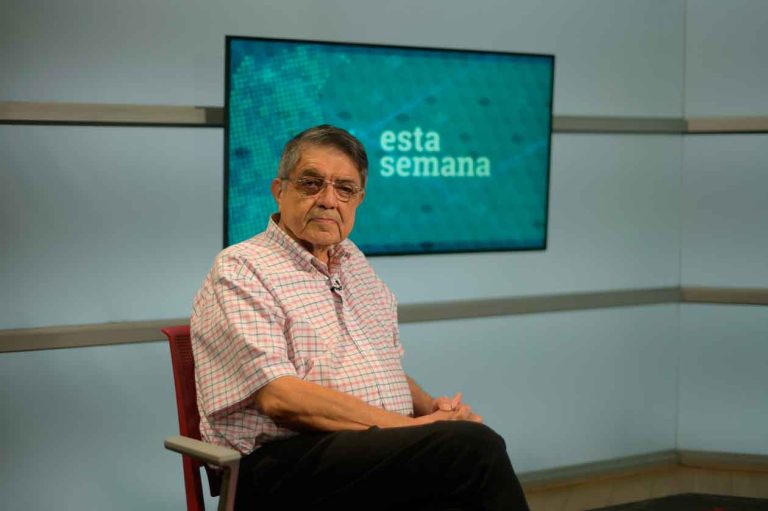

In an interview with Eldiario.es the writer confirms that he will remain in Spain in exile

When the Sandinista revolution overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, Sergio Ramirez was one of its most prominent leaders. Together with Daniel Ortega, Violeta Chamorro, Alfonso Robelo and Moises Hassan, he formed part of the triumphant guerilla movement’s first government junta. He served as Daniel Ortega’s vice president from 1985 until the 1990 elections. When the Sandinista government lost that election, their ways parted, and Sergio Ramirez ended up dedicating himself fully to writing.

Ortega, on the other hand, fought to recover power, with the intention he has now confirmed of never again letting it go. In 2018, Ortega’s police forces violently attacked the population that had poured out in massive demonstrations, tired of the constant poverty and arbitrary government responses. Hundreds died, and the tensions persists.

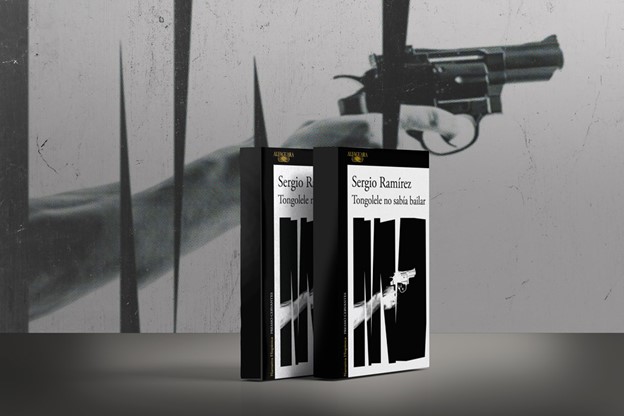

Those uprisings led to the creation of Sergio Ramirez’ latest novel: Tongolele no sabia bailar [“Tongolele couldn’t dance”], recently released by Alfaguara publishing. The story portrays the president of Nicaragua and his wife and vice president Rosario Murillo in all their vile capriciousness. “Nicaragua is a story of repetitions,” Ramirez says. “In the 70s, the dictator was Somoza; now it’s Ortega.” “Despite everything, though,” he adds, “I don’t regret the revolution.”

The mother of“Tongolele”, the novel’s protagonist, was very irritated that in Nicaragua over 69 metal “Trees of Life” had been erected. How important are these trees today in your country?

They’ve taken on major symbolic importance, since it’s a regime that guides itself by a series of unwritten esoteric rules. Sai Baba is the high priest of that pseudo religion. All of this stems from the personal beliefs of the President’s wife and vice president, Rosario Murillo, and from her personal habits of interpreting the world from a magical perspective. For that reason, when the 2018 uprisings began, the first victims were the metal “Trees of life” Murillo had installed throughout Managua. People focused their energy on toppling them. Hundreds of people massed to do this, but it was only a partial felling. The repression followed, and many of the trees were left standing while others are being “replanted”.

History repeats itself: in 1979, the headlines blasted tales of the Army’s repression of demonstrations; beginning in 2018, the headlines were nearly the same.

Nicaragua has a history of repetitions. It’s a story that always ends up chasing its own tail. The priests have been important figures in the great waves of changes the country has gone through. They were major figures in the Somoza era, with a number of priests committed to the Gospel of the Poor and identified with the Vatican II Council. Those priests had a lot to do with the revolution. From the Literacy Crusade, led by Father Fernando Cardenal, a Jesuit priest and brother of [acclaimed poet] Ernesto Cardenal, up to the hand offered by Gustavo Gutierrez, the great Peruvian theologian, with the Pastoral letter that the church issued in support of the revolutionary process.

What does Pope Francis have to say about what’s occurring?

I don’t know. Pope Francis has maintained a silence regarding the situation in Nicaragua that‘s been heard all over the world. Monsignor Baez, who’s the role model for the bishop in the novel, was dispatched to Rome as part of an agreement between the Vatican and the Ortega regime. Supposedly, he was called away in order to receive a position in the Roman Curia. However later no one paid any more attention to him, and he ended up living in Miami with his family.

Are people in Nicaragua waiting in any way to hear the Pope’s voice at this moment?

It would be desirable for all the faithful Catholics in Nicaragua, who make up half the population, to hear what the Pope has to say regarding the barbarities that began happing in 2018, and that continue occurring now with the arrest of so many people, with the unstoppable growth in the number of political prisoners.

The elections will be on Sunday November 7, and in the last months all the candidates who could have overshadowed Ortega have been imprisoned.

The candidates that are left are all a mirage created by the regime. There’s an amusing list of the candidates for Congress those miniscule parties cobbled together at the last minute. In these lists, the presidential candidate heads a roster made up of their siblings, their uncles and their cousins. The Nicaraguan model is ever closer to that of the former Eastern European countries, where the rulers were elected with 99% of the vote.

Who is Daniel Ortega today?

He could have gone down in history as a revolutionary leader, but he’s going to be judged as a tyrant, a dictator from the old school of dictatorships that have always existed in Latin America. The ideological color doesn’t matter – without a doubt, he’s a dictator. Without qualifying adjectives. A dictator, period.

You had a very close relationship with him for a long time. You supported the revolution, you formed part of the first Sandinista government junta and later came to serve as Vice President with Ortega as President. Didn’t you see any of this coming?

Looking at it from the point of view of a novelist, which is how I like to look at things, people change, people evolve. Daniel Ortega spent seven years in jail for robbing a bank, and he was freed by a commando group in which Hugo Torres participated. Today, Hugo Torres is in prison by order of Ortega. That gives some idea of how that person – who surely was grateful at that time for the commando actions that got him out of jail – behaves today towards his former liberators. I believe that one of the most definitive transformative elements that affects human beings is power, ambition, the thirst for power. That’s a universal theme in literature. I’m thinking of Macbeth.

So you think it’s the lust for power that changed Ortega?

Yes. That is, the determination to return to power and never again to leave. He was always convinced he’d made a mistake by turning power over to Violeta Chamorro following his loss in the 1990 elections, because that meant losing what he considered the Revolution. The Sandinista Party foundered with that defeat, because it was financed from the public treasury. The Army went and sought its own independent status as an institution, as did the police. So the kingdom he believed in, crumbled.

Did you ever think that those elections should never have been called?

No, I always believed that there was no other way out, except to call for democratic elections. I believe the Sandinista Front had two great moments: one in 1979, when they took power through force of arms; and the second in 1990, when they left it because of the people’s vote. That could have constituted a double, an enormous prestige, for the Sandinista movement. It was the first guerilla movement I know of that left power because it lost an election. But Ortega himself ruined it, by conspiring against Mrs. Chamorro, seeking to overthrow her, to destabilize her.

You’ve just decided to remain in exile in Madrid. Why can’t you return to Nicaragua?

Before I left Nicaragua, they called me in to testify in the case of Cristiana Chamorro, [former independent presidential candidate, now under arrest] who they’re accusing of money laundering. I direct a foundation named after my mother, Luisa Mercado, which maintained a cooperation agreement with the Violeta Chamorro Foundation – which Cristiana headed – to organize journalism seminars and workshops with their support. Hence, they [the public prosecutor’s office] called me in. However, in reality, what they really wanted, as we say in Nicaragua, was to check the boxes. It was a warning. They were sending everyone to jail, adding more and more prisoners. So, when I finished a medical treatment in the United States, I decided to go to Costa Rica. Once there, I found out about the arrest warrant the regime had issued for me, accusing me of the same crimes they were accusing Cristiana of.

Why have you decided on Spain for your exile?

I feel good here. Even though I’ve been here infinite times, it’s a new experience living permanently in Spain. I made the decision together with my wife. It seems to me that returning to Central America means beginning to breathe once again that toxic atmosphere that triggered my physical decline. I want to put an ocean between myself [and the region] and practice here the search for what I’d call a spiritual peace, even though that may not exist.

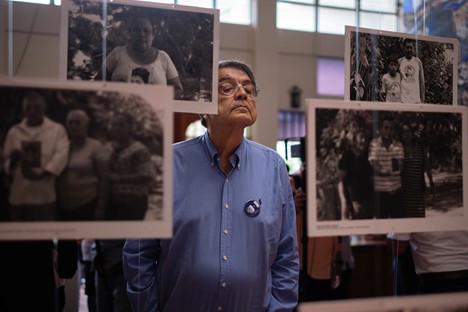

One of the immediate victims of the situation in Nicaragua has been journalism. Once again, the situation in that respect is very similar to the times of Somoza…

There’s no free press in Nicaragua. They shuttered La Prensa [Nicaragua’s main newspaper, whose physical installations were bombarded by Somoza in 1979]. They began by refusing to release the newsprint shipments from Customs, and later the newspaper offices were occupied by the police. Now, the digital edition of the newspaper is put out clandestinely in Nicaragua. There are many journalists in exile, and small electronic media outlets have been born, which are the ones working to maintain a very important journalism now in Nicaragua. We shouldn’t overlook the exile of Carlos Fernando Chamorro, like myself a member of the Gabo Foundation’s advisory board. He had to leave the country clandestinely to avoid being imprisoned. There’s a warrant out for his arrest, just like the one against me. He’s now running Confidencial, his media company, from Costa Rica.

When Somoza in Nicaragua closed all the media, underground journalism was born. The journalists went to the churches and read the news from the main altar, informing people what was happening: the repression, the missing young people; the dead; the bombing of the neighborhoods. Now there’s a new underground journalism, which is this being carried out through digital media. They can’t interfere with these sites, unless they impose an electronic blackout all across the country.

Who’s sustaining Ortega from outside?

Russia, Venezuela, Cuba, Iran and Turkey are his allies. Erdogan, Turkey’s ruler, defends Ortega; Putin defends Ortega; the Ayatolas defend Ortega. But when it comes time to translate this into concrete support, I don’t know what they’re doing. The most that Putin does is to send some buses that aren’t even properly equipped for the tropics – you can’t open the windows. In Nicaragua, these break down within a year. I’d love to know what real economic assistance they’re supplying, beyond the presence of intelligence and security forces. That clearly exists, because there’s a bunker of Russians in Nicaragua, operating intelligence communications systems. There’s also some Cuban and Venezuelan collaboration in matters of intelligence and security.

What role is the United States playing?

A very contradictory one. President Biden, in his speech before the United Nations, didn’t include Ortega in his list of dictators. On the other hand, the US Secretary of State speaks very forcefully against Ortega. Nonetheless, the International Monetary Fund awarded Ortega a full U.S. $370 million dollar package. It seems to me that this contradictory policy is because Nicaragua isn’t a priority for the United Sates, in the same way that Venezuela is.

There’s no free press, the opposition party leaders are in prison, the opposition to the regime is in the hands of the youth, but at a very high cost in lives…

Forty thousand have gone into exile just since May, not to mention the thousands that had already done so previously. However, the seeds of resistance are always there. They can’t change that, nor subdue it, however much they try to seal it under a lead slab. In the last Gallup poll, only 19 percent of the population said they’d vote for Ortega. If there were true elections, some 65 percent would vote for any of the candidates that are today in prison.

This interview was originally published in Spanish en Eldiario.es and traslated by Havana Times

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D