6 de febrero 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

A Salvadoran academic and journalists caution against the message of the “Bukele virus,” in which “the new order is what we used to call dictatorship”

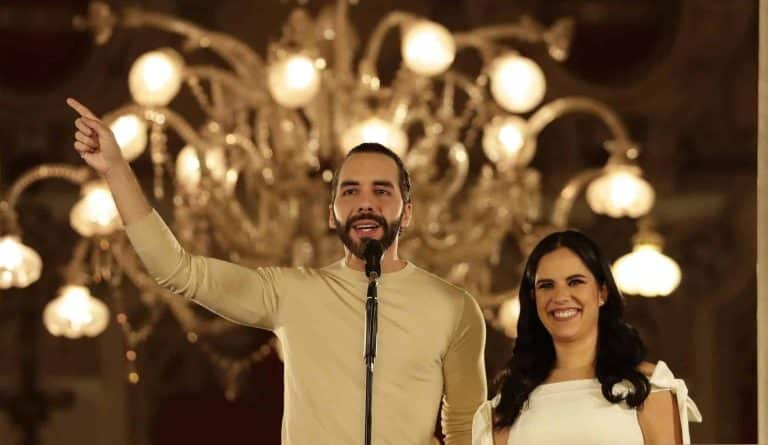

The current president and reelection winner, Nayib Bukele, speaks from the National Palace with his wife Gabriela Rodriguez. EFE | Confidencial

President Nayib Bukele proclaimed himself the elected winner with 85% of the votes and 58 of the 60 deputies in the Legislative Assembly, without waiting for the preliminary results of the Electoral Tribunal this Sunday, February 4. He preserves absolute control of all state powers in El Salvador.

In an interview with Esta Semana and CONFIDENCIAL, academic Amparo Marroquín, director of the Communication Department of the UCA, and journalists Cesar Fagoaga, director of Factum Magazine, and José Luis Sanz, correspondent of El Faro in Washington, warned about the message sent to the world by the “Bukele virus,” in which “the new order is something we used to call dictatorship.”

“The international community is applauding an authoritarian model that supposedly works in El Salvador and that is what it is validating, even though laws are not respected in El Salvador. And the big problem is that this authoritarianism is being replicated in the continent, with this newer form of disrespecting the laws,” said Fagoaga, of Factum magazine.

Communication expert Amparo Marroquín warns that the state of exception will continue to be a “permanent” feature in Bukele's new presidential term.

Marroquín explained that “people have a very pragmatic and short-term reasoning” to allow Bukele a blank check for the outcome of his citizen security policy against the gangs. “He has solved a problem for me today. I was afraid, I couldn't move around the city, and this man had solved it. And as long as he continues to solve my daily life, I will continue to support him, even if it means losing certain constitutionally established rights, which I didn't have in my daily life anyway," said Marroquin.

For his part, José Luis Sanz, correspondent of El Faro in Washington, questioned “the double standards and the complicit silence of the foreign policy of the United States, of other multilateral organizations, or the European Union,” which are endorsing Bukele's unconstitutional reelection. But he admitted that, unlike Guatemala, with the democratic movement led by the current president Bernardo Arévalo, in El Salvador “there is no alternative, no path or proposal from the civil society, or an articulated democratic opposition. In the elections of Sunday, February 4, “the population had no real alternatives, other than voting for Bukele, and that is a collective tragedy for our democracy,” he said.

What does this first presidential reelection of Bukele mean, with absolute control of the Legislative Assembly and all the powers of the State? Are there any changes expected concerning the first presidential term?

José Luis Sanz: First, it is the definitive normalization of the fact that Nayib Bukele is above the law. President Bukele, based on his popularity, has challenged the institutions that he did not control, which has been a process of co-opting the entire institutionality of the country very quickly. In 2020, when he had been in power for less than a year, he began to challenge the institutions. During the pandemic, he did not comply with direct mandates from the Constitutional Chamber or other systems. Recall that he had been in power for only nine months when he entered the Legislative Palace with the Army.

This is the ultimate normalization of Salvadorans' desire for a Bukele government. Their support and Bukele's desire to consolidate himself as an absolute leader and have absolute control of the country is above the law. It is the ultimate consolidation that Bukele either reforms the laws at his whim or simply breaks them.

What are the implications of a president above the law? This reelection violates at least six articles of the Constitution that prohibited consecutive reelection, thanks to a reinterpretation of the Constitution by the Supreme Court that Bukele appointed. Does this have any implications for the national or international legitimacy of Bukele's presidency?

César Fagoaga: This cannot be understood without the absolute control that Bukele has over the Salvadoran State, and this cannot be understood either without the silence on the part of the international community and the applause he has received many times. There is an elephant in the room, which right now is known as the “Bukele model,” which for us is more like the “Bukele virus.” It is often mentioned as something that is working in El Salvador and we [the international community and El Salvador] applaud it.

What is behind it is an absolute disrespect of the laws. The real “Bukele model” is to disrespect the laws, it is corruption at the highest level and many times to have a criminal government, as has been demonstrated this week by journalistic investigations.

The international community is applauding an authoritarian model that supposedly works in El Salvador and that’s what it is validating, even though laws are not respected within El Salvador. The big problem is that it is being replicated throughout the continent, not only with an older form of authoritarianism but also with this newer form of disrespecting the laws.

This Bukele phenomenon had, over these four years, a central pillar in its government strategy which has been the state of exception for two years. It has given him enormous political support and has strengthened his popularity in the fight against gangs and the restitution of citizen security, which has produced a change in El Salvador. Is the state of exception temporary or permanent?

Amparo Marroquín: Everything points towards a permanent state of exception. What is coming is the normalization of the state of exception, as a common moment in the daily life of the people. And then, this reasoning: if we have lost certain constitutional guarantees, we have gained in daily life in security. That is the reasoning of the great majority of people who are supporting Nayib Bukele.

What we are seeing from the university is that people have a very pragmatic and short-term reasoning of what is happening: he solved a problem for me today. I was afraid, I could not move around the city in everyday life, and today, this gentleman has solved it. And as long as this gentleman continues to solve my daily life today, I will continue to support him, even if this means losing certain constitutionally established rights, which I did not have in my daily life anyway.

Vice President Felix Ulloa, who has been reelected with Bukele today, told the New York Times in an interview that, if it is true that they are dismantling democracy, he said, we are eliminating it and we are replacing it with something new. What is the new thing?

José Luis Sanz: The narrative is that they are building something better than democracy. A new concept of democracy is something that has been between the lines constantly in Bukele's discourse. The idea is that there is nothing more democratic than popular support, evidently today we have seen it expressed at the ballot box. But regardless, this was a formality that within his discourse seemed unnecessary because popularity is what allows him.

Something very shocking has happened in the last weeks and months in El Salvador. Nayib Bukele who is on a supposed leave of absence from the presidency to campaign, among other things, has not even had a public appearance during the campaign, because it is not necessary. So, in reality, there has been a non-campaign because I think what they are trying to focus on is the idea that it is not even necessary to vote. And that is because we all supposedly know what we want as a country. And it’s Bukele.

It is a disarticulation of the need to participate, of the need to discuss, but it is based on the idea that this is an evolution of democracy, a kind of virtual democracy. And this seems to me to be extremely dangerous because of the power of normalization it has, not only in El Salvador but also in the region.

As journalists of El Faro, Factum magazine, you have documented acts of corruption, arbitrary detentions in large numbers of victims of what some people call “collateral damage” of the state of emergency, or even the agreements between Bukele and gang leaders, who have been taken out of jail and then [police] seek to recapture them. Does this have any implications for Bukele's presidency in the public opinion for the population?

César Fagoaga: Bukele is a publicist who has done his job very well. Despite the strong investigations and journalistic evidence, it has not changed the majority support that Mr. Bukele has.

This week it became known in El Salvador, and this statement may sound strong, but it is duly supported, that we have a “criminal government,” a government that made pacts with gangs, a government that set up an independent commission together with the Organization of American States to investigate corruption and when it found corruption it buried it, a government that has institutions that are working for its public officials, for its ministers, for its deputies, giving them credits to buy houses and luxury mansions.

Mr. Bukele has been able, with a campaign that has been running for more than five years, to get people not to believe in this, so that people say – it’s not a problem, it’s what we want because he has solved the main problem we have –, which is security. And it does not matter if we are not complying with the Constitution, if we are not complying with democracy, it does not matter if we are entering a dictatorship. If Mr. Bukele is fulfilling the need I have, which is to feel safe, not to continue living in a country as violent as El Salvador, I am going to allow him, I am even going to allow him to be one more thief, to be one more criminal, because we can already speak forcefully of a criminal government.

El Salvador is embracing a dictatorship, 90 years later, with applause, precisely because the Government has been capable enough and has allocated a lot of resources so that people applaud these kinds of things so that people feel safe and do not care about what they are leaving or what they are losing if they are supposedly gaining the possibility of being free.

Can independent journalism, democratic civil society, centers of thought, and universities develop under this climate of a state of exception and absolute power, or do they feel threatened or restricted?

Amparo Marroquín: I believe that in a culture as authoritarian as ours, in general people can feel threatened. The question for me is not whether we can, but whether we should. I think we always can. The history of Central America in general is a history of creative resistance to different forms of authoritarianism. So the question is, what should be the processes to continue exercising critical thinking, to continue building research, and to continue, in some way, showing critical discourses that are counterweights to such a totalitarian power as the one that continues to be configured in Salvadoran society at this time.

Some countries are already talking about replicating the Bukele model. Although at the international level, some questioned the re-election project that was consummated today, subsequently there has been a certain acceptance or complacency, because that is the will of the Salvadoran people.

José Luis Sanz: The opposition, the politics, the partisan construction, evidently, to a great extent, due to the communicative and economic repression of the Government, has not been able to regenerate itself. And in those moments there is a major challenge. And the truth is that we, civil society, have not been able to find a way to build a proposal from the failure of a single opposition candidacy.

What is certain is that there are no real alternatives for the population to vote for Bukele, let's accept it, and this is a collective tragedy for our democracy. The great contrast with what has happened in Guatemala is not only due to the double standards and hypocrisy of the foreign policy of the United States, other multilateral organizations or agencies, or the European Union. It also has to do with the fact that, in the Guatemalan case, an international community was resigned to normalize and accept the results of a fraudulent election and accept the victory of whoever it was.

When there was an alternative, a candidacy with a democratic vocation and popular support, the international community felt comfortable because the political price for them was lower and they put the burden and bet and worked hard with the Guatemalan society so that (Bernardo) Arévalo would come to power.

I think it is important that we admit that at this moment the international community – and I do not justify it because the double standard and the complicit silence seems to me tragic and hypocritical –, but it is also true that from their pragmatism they do not find the way to build their narrative of, we are supporting an opposition that is vigorous and identifiable. There is no articulated opposition in El Salvador.

This article was published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff. To get the most relevant news from our English coverage delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to The Dispatch.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D