1 de noviembre 2022

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

The hunger strike of political prisoners Dora María Tellez, Miguel Mendoza, Irving Larios and Roger Reyes and 24 others.

The hunger strike of political prisoners Dora María Tellez

As I post this article, former guerrilla commander Dora Maria Tellez; sociologist and social fighter Irving Larios; journalist Miguel Mendoza; and Attorney Roger Reyes have logged over 30 days of a hunger strike in Managua’s El Chipote jail. Meanwhile, 24 other prisoners locked up in the penitentiary known as La Modelo are also making use of this drastic decision as their only way to demand their rights as prisoners.

The Ortega-Murillo dictatorship has shown no sensitivity whatsoever to such basic demands as ending solitary confinement; allowing imprisoned mothers and fathers to receive a visit from their children; letting the prisoners receive books, medical attention and medicine, not to mention sunlight and food. The regime’s response has been – “Nothing!”

Ortega and Murillo have already demonstrated their criminal vocation when they confronted the popular protests of 2018. Now, once again, they’ve put them on full display with the permanent conditions of torture they submit the prisoners to, and the punishment they’ve meted out to those on strike – increasing their isolation by blocking family visits. These too are crimes against humanity.

Ortega’s unconditional followers are offended when I compare him with Somoza and affirm that Ortega is worse than that tyrant. But if History is good for anything, it’s as a teacher. I wish here to leave some reflections that support my affirmation that Ortega is much worse than Somoza. If, up to now, he hasn’t bombed cities and engaged in large-scale genocide, it’s because the level and forms of the struggle [against him] haven’t required him to.

Hunger strikes have been historically used to try and win some concessions, in contexts where those demanding have no other way of making their needs felt. It’s a drastic measure, in which the strikers put their own bodies on the line – their health and even their lives – as an instrument of struggle, especially in conditions where individual action is nearly the only possibility that exists. given the denial of the Rule of Law.

Mothers and relatives of political prisoners begin a hunger strike at the Red Cross. Photo: La Prensa

The hunger strikers’ objective isn’t to die; however, if the hunger strike is prolonged, this occurs. The best-known case in Nicaragua was that of nurse Silvia Ferrofino, who participated in a contentious strike of the health workers, which was eventually suspended due to the critical state of the participants. The repercussions triggered Silvia’s death in May 1979.

Important figures have seen her as representing a non-violent means of struggle.

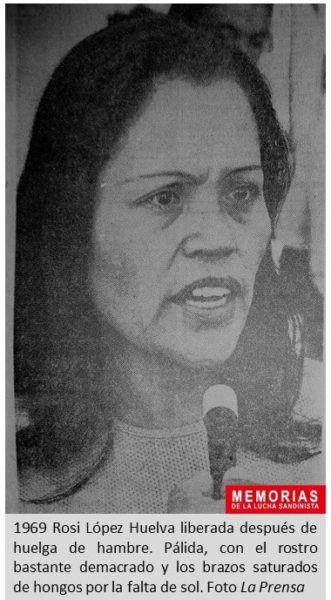

The best-known hunger strikes in Nicaragua were practiced by political prisoners and their families, later joined by priests, union leaders, and students, some continually and some intermittently. In 1969, Rosi Lopez Huelva and Doris Tijerino Haslam began a hunger strike demanding Rosi’s release, since she had already served her six-months sentence for “threatening the Constitution”. They were also demanding improvements in their jail treatment, because they weren’t receiving either sunlight or medical attention. The Somoza dictatorship released Rosi, who was described as she left the prison: “Pale, with a gaunt face and the skin on her arms riddled with fungal infections, for lack of sunlight.”

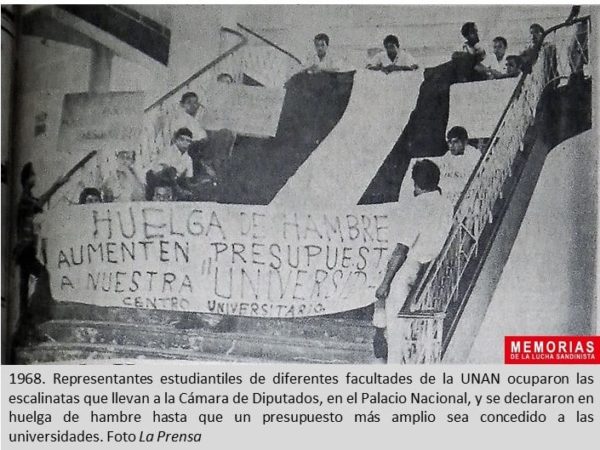

Other hunger strikes during those years included one of the health workers in Granada, and one led by the university students, who occupied the steps of the National Palace while Congress was in session, in demand of a larger budget for the National University (UNAN). These students displayed signs saying: “Fewer soldiers, more students!”, and “97 million [cordobas] allocated for the National Guard – 7 million for the UNAN!”

Can you imagine how Ortega would react if students today engaged in a sit-down strike in front of the National Assembly?

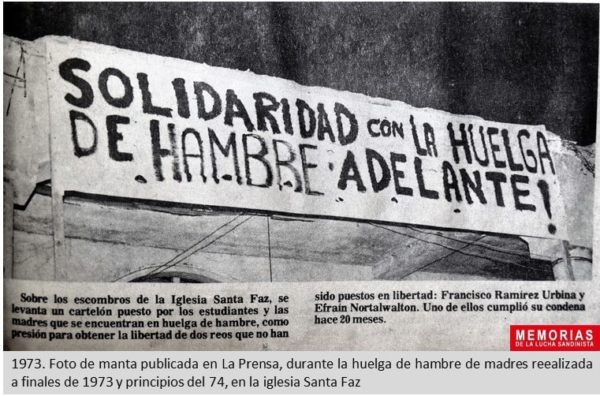

After 1970, hunger strikes were recurrent events, except for 1975 and 1976 when all guarantees were suspended under the State of Siege. I especially recall the 1971 strike – a powerful hunger strike launched by the political prisoners and 12 relatives, among them Lydia Saavedra, mother of the current dictator. After a series of church takeovers, student strikes and sustained mobilizations, the unrest forced Somoza to release eight political prisoners: Catalino Flores, Doris Tijerino, German Pomares, Rolando Roque, Arnulfo Orozco, Ramón Ernesto Rizo, Adan Loza Talavera y Mauricio Secundino. All of these prisoners had participated in the armed struggle not civic protests, like those detained today.

These struggles weren’t exempt from repression, tear gas, sieges from Somoza’s National Guard, beatings of sympathetic religious leaders, and short-term detentions. However, the press was allowed to function and offer media information about these happenings.

In contrast, what’s the situation under the current dictatorship? Conducting hunger strikes is unthinkable. Remember the attempt made by eleven mothers of political prisoners, who began a hunger strike at the San Miguel Archangel Church in Masaya in November 2019? The response of today’s dictatorship was to install a police cordon, closing off an area of several blocks around the church; cut off all electricity and water to the church, and imprison those who tried to bring aid. Among the notable events of that time was the arrest of 13 young people, later known as Los Aguadores, the water carriers, when they tried to take water to the mothers. Without water and totally isolated, the women and sympathetic priests had to abandon the church.

Do mothers have a right to join their children’s hunger strikes? Why was it legitimate for the mothers of Sandinista children to mount a hunger strike, but now, for this new generation of family members of Ortega’s political prisoners, it’s no longer legal?

UNAN Student leaders occupied stairways leading to the Chamber of Deputies of the National Palace and declared a hunger strike until a greater budget was allocated to the universities. (Photo: La Prensa)

On January 24, 1972, the political prisoners being held in the La Modelo penitentiary began a hunger strike; they were joined later by some family members and other sectors. Their demands were : 1) Allow the regular flow of correspondence without imposing shameful measures; 2) Allow radios and literature in, without limiting the quantity; 3) Free entrance of money and medicine; 4) Allow families to bring them food during regularly scheduled Sunday visits; 5) An end to cell searches; 6) End the use of striped uniforms; 7) Access to daily sunlight; 8) Allow physical exercise; 9) End the threats of clubbing from the guards; 10) Remove the mesh separator during family visits; 11) Allow the prisoners to remain in the hallways from 5 am until 10 pm, like the common prisoners. 12) End the solitary confinement of Jose Benito Escobar, Julian Roque Cuadra and Lenin Cerna; 13) Have the mayor present former soldier Francisco Ramirez [sentenced to six years in jail for turning in his Garand rifle to the FSLN. He hadn’t been recognized as a political prisoner, and nothing was known about his condition.]

Do these prison demands sound similar to the ones being raised today? These things happened 50 years ago, during which time humanity has undeniably advanced in matters of human rights. Today, we also have the Nelson Mandela Rules [UN-established minimum rules for the humane treatment of prisoners]. Doesn’t it seem brutal and cruel that people detained for political reasons today should have fewer rights than those who were in prison during the Somoza dictatorship, half a century ago?

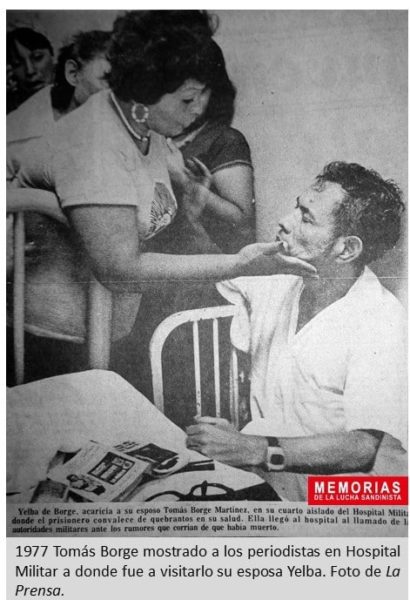

It’s important to stress that in those days independent journalists were able to enter the prisons and confirm the prisoners’ situation. They took photos and wrote their articles. Also, at different moments, these struggles were backed by priests and bishops. At the time, we Sandinistas considered it fair and just that the religious leaders should join in to support the popular demands and human rights. Is there any single independent media outlet today that’s allowed to circulate in Nicaragua? Are the media allowed to enter the Military Hospital or the prisoners’ cells to cover the state of the political prisoners?

What does the dictator do today? He persecutes, imprisons, banishes, and forces into exile the bishops and priests, all the while disparaging them with detestable epithets, for the actions they undertake when they raise the same banners of freedom and justice that they demanded back then of the dictator Somoza. These aren’t my inventions. As evidence of this persecution, we currently have Bishop Rolando Alvarez and several priests in jail and accused of crimes, plus dozens of priests and nuns banished or in exile.

In January 1977, another hunger strike began.

In February of that year, although Nicaragua was still in a State of Siege, Somoza allowed Victor Umbricht and Raymont Chevally, delegates of the International Red Cross, to visit the prisons and converse with the Sandinista prisoners there. In addition, following months on strike, Tomas Borge received medical attention in the Military Hospital, and his family was later allowed to see him as well as the media, who published numerous photos of him.

Tomas Borge was photographed at the Military Hospital during a visit of his wife. Photo: La Prensa

What is the current dictator doing today? He has expelled the human rights organizations and the coordinator of the International Red Cross. He’s closed all the national watchdog organizations that monitor human rights – the Nicaraguan Human Rights Center (CENIDH), the Nicaraguan Pro-Human Rights Association (ANPDH) and the Permanent Commission for Human Rights in Nicaragua (CPDH). And don’t even think he might allow the media direct access, to confirm the prisoners’ condition.

The cruel Somoza dictatorship allowed Tomas Borge to be displayed – famished and deteriorated. But what happened with Hugo Torres, a hero of the 1979 revolution and Ortega’s political prisoner? He became gravely ill in jail in December 2021, was removed from his cell to no known destination. It wasn’t until his death that a tiny notice from the Prosecutor’s office announced his demise, without offering any kind of explanation.

Up until right now, the heroic hunger strike of Dora Maria and the other political prisoners has received a completely inhumane response from the regime. Instead of bending, it has intensified the terrible jail conditions. For over sixty days now they’ve not allowed family visits, keeping the prisoners completely isolated in order to cover up their critical situation.

It’s been well established that we’re faced with a dictatorship of terror, that has no comparison with the one we had already experienced in Nicaragua. The barbarity of the Ortega regime’s response to the current hunger strike makes us aware of the very serious risks the prisoners on strike are facing. Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo want them to die, or at least be left scarred for the rest of their lives. He wants to break every one of the bones that support their consciences.

It’s urgent that the peoples of the world make their solidarity felt, spreading the information, the denunciations. It’s also urgent that we Nicaraguans hasten to find new paths of resistance, to challenge the dictatorship’s terror, in order to save Dora Maria’s life and that of all the people detained for reasons of conscience.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Guerrillera, revolucionaria y política nicaragüense. Participó en la insurrección contra la dictadura somocista. Exdiputada de la Asamblea Nacional. Fundó el disidente Movimiento por el Rescate del Sandinismo. Tiene una licenciatura en Ciencias Sociales y una maestría en Derecho Municipal de la Universidad de Barcelona, España. Es autora de la serie "Memorias de la Lucha Sandinista".

PUBLICIDAD 3D