25 de enero 2021

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

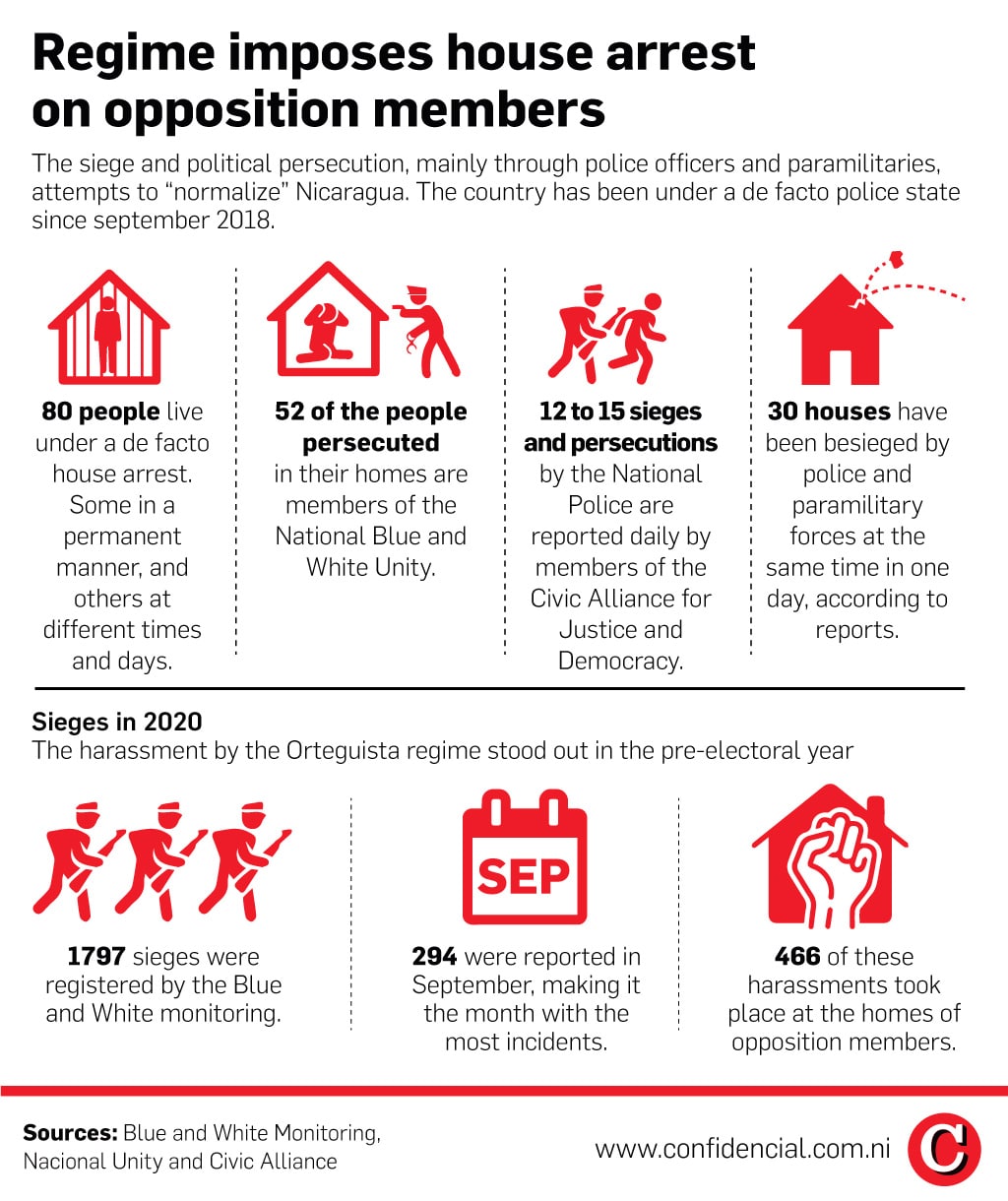

Police officers, civilians and paramilitaries prevent the free mobilization of opposition members, violating constitutional rights

Illustration: Confidencial

Martha Alvarado remembers the joy she felt when she was informed that she would be honored on International Women's Day, March 8, 2020. Soon that emotion turned to rage because the day before the ceremony several National Police patrols were stationed outside her home to prevent her from leaving.

They arrived at six in the morning of March 7, placing a patrol in front of the main gate of her house to prevent anyone from leaving or entering the place. Indignantly, she went outside to protest and one of the police officers replied that she should just go back inside because they were “just following orders”.

This was not the first time she had been locked up. The incident reminded her of the nine long days she was trapped in the San Miguel church in Masaya, in November 2019, when she and other women began a hunger strike demanding the release of her family members who were political prisoners. On that occasion, dozens of police officers and Sandinista mobs prevented the delivery of food to the people inside the church and did not let them leave.

Alvarado was demanding the liberation of her son, Melkissedex Antonio López, now released from prison. “The dictatorship kept my son in prison for 386 days. I was in the streets, I was on a hunger strike in San Miguel (parish), and it (the dictatorship) began to prevent me from leaving my own house,” she said.

After that occasion, the police began to arrive at her home, located in Managua's VII District, on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. They stayed outside for hours, "besieging and intimidating".

However, the police siege has increased since December 4th, when she was elected as a substitute for the representatives of the sector of the territories of the opposition Civic Alliance for Justice and Democracy.

“Now they come every day, they spend Monday to Monday outside my house, intimidating anyone who wants to get close. They don't let me go out in the street. They don’t leave until four in the afternoon, so they practically have me in jail,” she says.

Her two children are allowed to go out, but they are followed when they go to the street. “It’s a permanent harassment for the whole family,” she says.

In the early hours of December 31, the police arrived at five in the morning to search the house, without a warrant or explanation. Once again they told her that "these are orders from above".

“Everyone in the house lives in constant stress with this situation. I let them in to convince them that there is nothing wrong with us because we are not criminals. There are six girls that live here, and it’s not fair that they have to see this harassment,” says Alvarado.

Esthela Rodríguez (middle) and Karen Lacayo (right), mother and sister of political prisoner Edward Lacayo, ‘La Loba’. // Photo: Courtesy

“It’s not enough for them that my brother is in jail, they still come here to bother us. They are holding me hostage in my own house… miserable murderers”, shouted Karen Lacayo, sister of Edward Lacayo, the political prisoner known as “the Wolf”, in a video she recorded with her cell phone on December 12, 2020.

Exhaustion and desperation caused Lacayo to confront the police who were besieging her house in the Monimbó neighborhood of Masaya. But the nightmare did not end. "I have been a prisoner in my house for forty days," she denounced.

Lacayo laments that she cannot go deliver packages for her brother, imprisoned since March 15, 2019.

At six in the morning on December 31st, riot police surrounded her house. Esthela Rodriguez, the mother of Karen and Edward, was thrown to the ground when she tried to leave the house to buy bread and milk.

"We are kidnapped in our own house, without any explanation," says Lacayo. That same night, during the New Year's Eve celebration, the police continued their siege. "They were in a combative attitude, and they wanted to prevent me from sitting outside the house," describes Lacayo.

"Get in, get in," is all they said.

The ongoing harassment also limits visits from family and friends. "Anyone who comes in is checked in and out. When they ask why, they are told that because I was at the roadblocks”, Lacayo explains.

Before, they let her leave the house, but they followed her everywhere. "On one occasion, in Managua, they stopped me and forced me onto the bus back to Masaya, they came with me, took pictures of me," she says.

However, she does not give up her claim. "We will continue to resist until we achieve the release of my brother and all the political prisoners. The fact that they are still outside the house is not going to stop us from continuing to denounce and fight," he says.

Since the social explosion in April 2018, the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo has maintained a siege against opponents in several cities in Nicaragua. However, since mid-2020, the siege and house arrest modality has increased. The upsurge coincides with the mobilization of opposition platforms to organize themselves in the territories in the face of possible elections and civic resistance against the police state.

The organizations have held meetings in municipalities and departments to establish boards or delegations; although the meetings have taken place in an atmosphere of siege, intimidation, and violence by the police and Orteguista sympathizers.

"The dictatorship continues to expand its forms of repression and human rights violations by having many opponents locked up in their homes, with the aim of preventing people from organizing in the face of a possible electoral process and to generate fear among the population," denounces Dr. Vilma Núñez, president of the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights (Cenidh).

The regime, she affirms, tries to show the message that "it is the owner even of your privacy, of your decisions". It is, she underlines, "a perverse act".

María Asunción Moreno, jurist, academic and member of the Civic Alliance, explains that "there is no argument or legal basis that empowers police agents to prevent the free mobilization or movement of Nicaraguans in the national territory in the way they are doing through roadblocks, searches, and sieges aimed at intimidating and threatening those who oppose the government.”

Róger Reyes is often chased by police officers who prevent him from leaving Carazo. Photo: Stereo Romance

Some opponents are prevented from leaving their homes, and others are prevented from leaving the city or the department, as is the case of Róger Reyes, a 34-year-old lawyer who is not allowed to leave Carazo.

Originally from Jinotepe, Reyes reports that he is a victim of constant police harassment. "Although it's not daily that they come outside my house, it's very constant. Sometimes they come dressed in civilian clothes, they have followed me in a car all over Jinotepe without caring that I'm just with my two daughters, four and two years old," he describes.

Reyes, the departmental coordinator of the UNAB in Carazo, explains that they prevent him from participating in political meetings, in masses dedicated to those killed in the 2018 protests, or in any opposition act.

"Stop screwing around, you can't leave," a policeman told him when he tried to go to an UNAB meeting. They told him they already knew where he was going and didn't let him go.

On January 7, they also entered his home, and they painted the phrase, "Ojo golpista. Plomo”, meaning “Keep an eye out, coup plotter. Plomo”, on his vehicle.

"That phrase and that invasion of the private property say a lot about the level of persecution, my wife can no longer sleep peacefully thinking that she can't be in the house alone,” he laments.

Former political prisoner Ivania Álvarez (right) on the day of her release. Photo: Carlos Herrera | Confidential

The first time the National Police tried to lock up oppositionist Ivania Álvarez, a member of the Political Council of the UNAB, was on September 25, 2019. "My house was fenced in for more than ten hours to prevent us from holding a march," she recalls.

Álvarez had gone out the night before, but her family suffered that confinement. The police presence intensified every time sit-ins or activities of the opposition were organized.

On one occasion, a plainclothes policeman threatened her to prevent her from going out. "He made the gesture of looking for a weapon in his clothes,” she says.

The persecution became daily. She was “accompanied” when she went shopping or out to eat anywhere.

"They even followed me when I went to the bathroom in a restaurant until I confronted them and told them to take me to the police station if they had anything on me,” she recalls.

In December 2019 she was summoned to the police station, along with other opponents from Tipitapa, but she was not allowed to leave her home that day.

"Whenever I go out, they stop me in the street. On December 24th, they detained me in the street and kept me under the sun for several hours," she says.

Three days later they took her car away. "They took it away with the crane and still haven't returned it to me. They sent me to the station and didn't give me an explanation, it seems that they want to steal everything," she said. Alvarez is convinced that "they want to spread fear among the population,” with these actions.

What I'm doing is not giving it any importance," she says, "because they're not going to stop the protest, I've already lost my job, I've already lost my fear.

Felix Maradiaga (left) and Juan Sebastian Chamorro (right) in an interview with Confidencial. Photo: Confidencial

On October 25, the executive director of the Alianza Civica, Juan Sebastian Chamorro, learned that he could not leave the capital, when he was not allowed to go to an activity. This was confirmed to him on November 13, when he was returned to his house in a patrol car. "They told me I couldn't leave and they took me back," he says.

On the way, they argued that he was "the subject of an investigation," but to date, he still does not know the reasons.

According to Chamorro, this form of repression follows "the Cuban method" of persecution. "It is a constant intimidation: where I move, the patrols follow," he denounces.

In his opinion, "Ortega is afraid that the Nicaraguan opposition can meet, can work, and can defeat him through civic and peaceful means.”

"This persecution and harassment is a sign of weakness. These abuses," he warns, "are not going to stop us in our struggle for democracy.”

On December 17, the police attacked Felix Maradiaga, of the Political Council of the UNAB, when he was trying to bring aid to the victims of hurricanes Eta and Iota in the Northern Caribbean.

Since then, he has documented several failed attempts through Facebook.

“The first objective of this type of arrest is to generate a legal limbo, because without being arrested, it makes it difficult to denounce nationally and internationally (...) they have immobilized us and effectively manage to not pay the political cost of arresting us,” he argues.

For Maradiaga, the "perverse effect" is to normalize the repression.

"It is so recurrent that some people begin to see it as normal, because for them you are not a prisoner, even though you are not free," he assesses.

He admits that the situation "is not as terrible as that of political prisoners," but claims that "it should not be normal" for people to be deprived of their liberty, from their homes, or in prison.

This article has been translated by Ana María Sampson, a Communication Science student at the University of Amsterdam and member of our staff*

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, con dos décadas de trayectoria en medios escritos y digitales. Fue editor de las publicaciones Metro, La Brújula y Revista Niú. Ganador del Grand Prize Lorenzo Natali en Derechos Humanos.

PUBLICIDAD 3D