Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

UCA has published a book bringing together the work of photographers who were documenting the hardest and most violent moments of the ongoing crisis

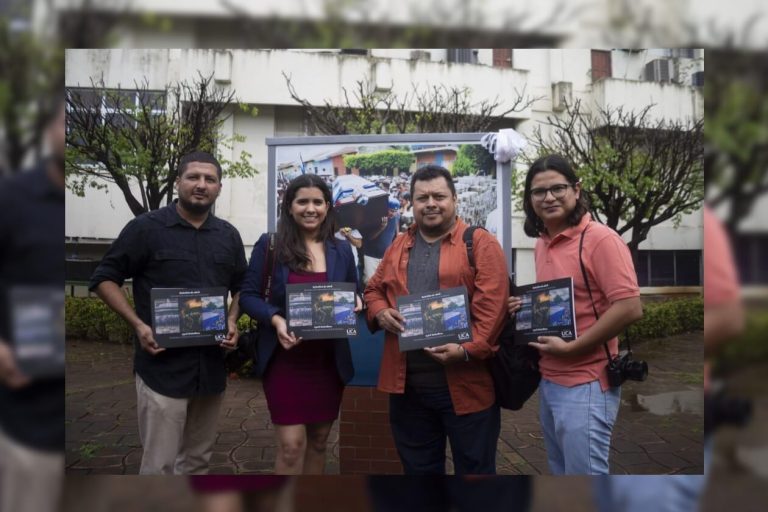

An event, “Photography in Times of Crisis: Narrating the Crisis through Images”, was held as part of the public launching of a book compiling hundreds of photos from the most brutal and violent months of repression touched off in Nicaragua in April of 2018. Three Nicaraguan photographers from different media outlets shared their experiences covering the protests in different parts of the country.

The book, April Uprising: Portraits of Repression and Resistance had an initial printing of 500 copies, which will be available to the public in the UCA publications office (which edited and published it), as well as in different bookstores in Managua. The book looks at different stages of the repression, examining the contexts in which the photos were taken.

Nicaraguan Photographer Claudia Gordillo curated the selection of photos for the book, and she talks about the extremely painstaking process leading to the final selection of images. “My main goal I was clear – to show the aggression against citizens, journalists and students, which the government has been trying to deny all this time,” Gordillo explained.

Special guests at the event included Carlos Herrera, from Confidencial and Niú, Óscar Navarrete, from La Prensa y Nayira Valenzuela, one of the few women in this profession, who documented the crisis for El Nuevo Diario. The three shared their experiences as they discussed technical issues, ethics and security, along with the emotional weight behind the images.

Nayira Valenzuela worked for El Nuevo Diario [which just closed operations on Sept. 27] for four years, but was still a student when the crisis exploded. As she shared in her comments, one of the most difficult things she experienced was living with that duality which at times did not allow her to separate her citizen identity from her identity as a photographer.

“The most difficult moment I remember was on [Nicaraguan Mother’s Day] May 30, 2018, when for some reason I ended up in the National Stadium where snipers were shooting at students who were left to defend themselves with only rocks and homemade mortars. I wanted to take a photo that would prove what I was seeing there, but my angle made that impossible, and pretty soon I had to escape, running out of there to save my life,” Valenzuela said.

For Carlos Herrera, photojournalist for Confidencial, one of the most difficult things was dealing with the stress produced by the ongoing task of documenting the uprising. He mentioned how difficult it was to seek professional help. “I think there were a number of technical and safety issues that we managed to deal with, one way or another, but the emotional impact is something more.”

Herrera comments that a sense of solidarity emerged within the profession, in part because nobody expected such a violent reaction from the regime and, unlike other years, the majority of the Nicaraguan photographers out on the streets were part of a new generation that had not lived through the war in the 80s.

Herrera has been working as a photojournalist for nine years and during the crisis, worked to broaden his vision beyond simply portraying the violence, looking as well to document what was happening around it. “In the most difficult months, getting into Masaya, full of barricades, was truly an odyssey and one of the strangest things was seeing, just a few blocks from where a “mini-war” between citizens and police was taking place, people pulling chairs out of their houses to sit and enjoy the cooler air of late afternoon,” Herrera recalls.

Óscar Navarrete lived through the war of the 80s, when he began his profession. He says that during the 90s he never imagined that he would see such levels of violence and death again in Nicaragua – and notes that what he saw in 2018 brought back many of those difficult memories.

What made the greatest impact on him was having to once again cover funerals and depict the pain of the mothers and other family members who had lost their loved ones. He has always tried to do his work in such a way that he is not invading the pain of those involved and is always respectful of what the families are going through.

“There were moments, during the hardest times, when the entire family was weeping for their loved one and I didn’t even think of taking out my camera, because my respect for such pain always came first,” he says.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D