3 de julio 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

My brother, Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, writes of his one year, seven months and eighteen days in Nicaragua’s “El Chipote” jail and under house arrest

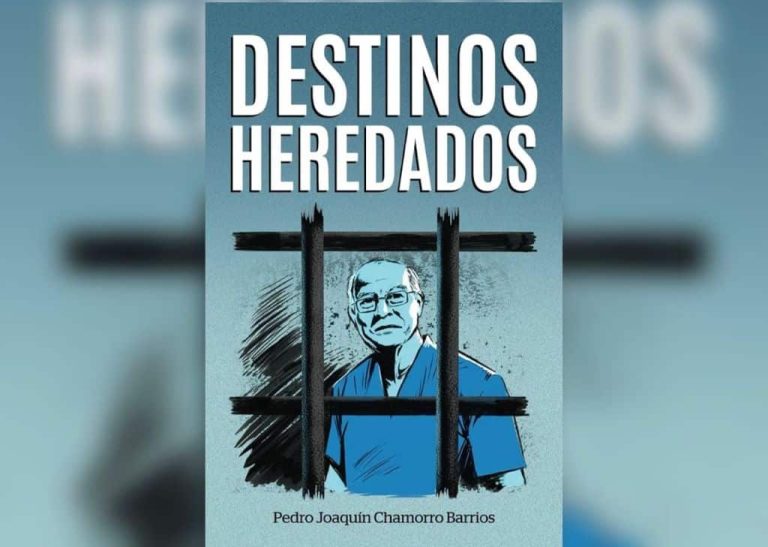

Portada del libro “Destinos heredados” del expreso político nicaragüense Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Barrios.

Destinos Heredados [“Inherited Destinies”] is the testimony of my brother, Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, on his ten months and nine days in the infamous “El Chipote” jail, and the nine months, nine days of house arrest that followed, when he was transferred after losing 50 pounds and with his health seriously deteriorating.

It all began as a cruel act of political vengeance imposed against him and dozens of others, both male and female: political and civic leaders, university students, rural activists, business leaders, intellectuals, journalists, priests, and human rights advocates. All at a time when the dictatorship of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo determined that imprisoning all the opposition leaders was the most effective way to annul any kind of competition in the November 2021 elections. Otherwise, the dictator was destined to lose.

The book is also a minutely detailed narrative from a journalist determined to describe with rigor, honesty, and truth the events he lived through. I read this manuscript for the first time when Pedro Joaquin – now banished to the United States – was sending me freshly written drafts of each of the book’s fifteen chapters. I read it again, now as a finished book, in one straight sitting. Its value as a historic document impacted me immediately, as well as the portraits of his relations with his cellmates, including Víctor Hugo Tinoco, Arturo Cruz and Jose Adan Aguerri. But, above all, it ensnared me as a reader because he has achieved the difficult feat of bringing alive what life is like in the dungeons of Latin America’s worst dictatorship. Moreover, he does so through a narrative that’s engaging and sprinkled with both humor and irony, as a medicine against grief and desolation.

Pedro Joaquin speaks of his experiences with no touch of rancor or exaggeration. He writes just like the person he is in his daily life – noble, balanced, politically moderate, a man who loves his wife and family, strongly tied to his Christian values and to the legacy of his parents and his nation. And, as he himself confesses, a person who always faces adversity with “ingenuousness and optimism.”

For example, in a totally natural way, without embroidering the events with adjectives, he describes the torture of being locked up in a jail where any kind of reading and writing is prohibited, including access to a Bible. “The only reading material that we prisoners had,” he writes, “was the label on a small 237 ml. bottle of Ensure, a drink containing a long list of vitamins and minerals.”

In the same way, he details the house arrest regime he was later placed under, “by order of Compañera Rosario and Comandante Daniel.” This represented an immense relief, in terms of being able to recover his physical and mental strength, but he was also forced to continue the policy of strict isolation, under permanent watch of four police officers who would take a picture of him at 6 am and another at 6 pm to confirm “that I hadn’t fled my own house.”

I was particularly moved by the chapter in which he tells of the four days that [now deceased] retired general Hugo Torres Jimenez spent in his cell, a time when the general was already in grave health and on the edge of death. Pedro Joaquin’s humanity and solidarity in becoming Torres’ nurse and companion in misfortune shine through, until his protests finally succeeded in having Torres taken out of the jail and sent to a hospital. Through his descriptions, the author bears exceptional witness to the direct responsibility that Nicaragua’s highest political authorities hold in the deteriorated health and death of Hugo Torres.

Destinos Heredados is also a homage to the resistance of all the political prisoners who suffered unjust imprisonment and were submitted to bogus trials in the jail itself, without the right to defense. These trials culminated in prison sentences of eight to ten years, for the supposed crimes of “undermining the national sovereignty,” “money laundering,” or “abusive management and undue appropriation and retention of assets.”

As he explains in his book, Pedro Joaquin proclaimed his innocence with dignity, as did all the political prisoners. None gave in. The Ortega-Murillo dictatorship was never able to fabricate a false confession or a guilty plea for the invented crimes they ascribed to the prisoners of conscience. They were never able to break them with their regime of torture and isolation, and that moral victory of the political prisoners symbolizes our hopes for the new republic with democracy and justice that we Nicaraguans deserve.

On February 9, 2023, 222 prisoners were released and put on a plane, banished to the United States, and stripped of their Nicaraguan nationality. Among them was Pedro Joaquin Chamorro Barrios. With this new act of vengeance, these prisoners recovered their freedom; meanwhile, however, the revolving door of the repression has once again filled the dictatorship’s jails with 141 political prisoners, and over a hundred more under de facto house arrest. Latin America and the world must not forget them. For the liberty of all Nicaragua’s political prisoners, I invite you to read Destinos Heredados.

Destinos Heredados is available in Spanish, as a print edition or a Kindle e-book through Amazon.com.

This article was published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times. To get the most relevant news from our English coverage delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to The Dispatch.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D