17 de septiembre 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

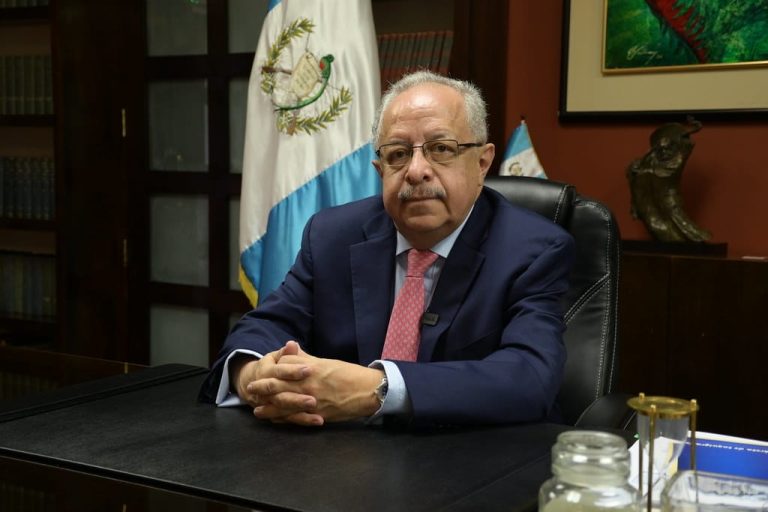

Guatemala-Nicaragua relationship remains “open” says Foreign Minister Carlos Ramiro Martinez. SICA impasse is Nicaragua's responsibility, he adds

Carlos Ramiro Martínez, Chancellor of Guatemala. | Photo: Confidencial

The Government of President Bernardo Arévalo in Guatemala welcomed the group of 135 political prisoners exiled from Nicaragua on humanitarian grounds and at the request of the U.S. Government, confirmed Guatemala's Foreign Minister, Carlos Ramiro Martínez, in an interview with CONFIDENCIAL. The official said that, although his country has provided all the possible migratory benefits, most of the former political prisoners are completing procedures to be relocated to the US.

He also maintained that the release of the political prisoners was the result of negotiations between the U.S. government and the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo. However, he added that both parties “were looking for a country that would receive them [the political prisoners]” and Guatemala was the country that was agreed on.

“It was a humanitarian matter and [in Guatemala] we are trying to do things in the best possible way,” stressed the head of Guatemalan diplomacy.

Foreign Minister Martinez also referred to the reasons why the Government of Guatemala will not publish the list of released political prisoners, the relationship between the Government of Guatemala and the Ortega-Murillo regime, and the lack of consensus to elect the Secretary General of the Central American Integration System (SICA), a position vacant since November 2023.

Why did Guatemala agree to receive 135 political prisoners exiled and released by Daniel Ortega?

The administration of President Arévalo is committed to democracy and to the protection and promotion of human rights. This is the reason for the act of welcoming these 115 (135) Nicaraguans. It is an effort of brotherhood. They are our historically linked neighbors, and that was the attitude of the Government.

Did your government have direct or indirect communication with the Nicaraguan government?

No, we did not. As far as we know, and I cannot speculate either, it was a negotiation process between the United States and Nicaragua. It took a good few months, according to what I am told, and it was fine-tuned little by little.

If the United States led these efforts, why didn't they welcome them in the United States, as happened with the group of 222 (exiled political prisoners) in 2023? What were the agreements between the (Joe) Biden administration and President Arevalo?

I do not know the extent to which the experience in practical terms was successful. I do know that (the U.S.) was looking for a country that would receive them. If it was part of the negotiation with Nicaragua. I do not have details, but I do know that the possibility of other countries was discussed and it was Guatemala that also accepted the Nicaraguan Government. What are we giving in exchange or what are we asking for? Nothing. They are not asking us for anything, nor are we going to ask for something in return, that is not the intention of the Government. It was a humanitarian issue. We are trying to do things in the best possible way.

Since when did Guatemala know that this release would take place?

About 10 or 12 days ago, Thursday 29 or Friday 30, we received a request for a meeting from the US Embassy in Guatemala. They asked with special interest that the meeting be with President Arevalo, not only with the Foreign Ministry. So we had the meeting, they presented the situation to us and the president did not hesitate for a moment to accept the request.

Five days have passed and the Ortega regime has not said a single word, it pretended that this never happened, neither did it publish the list of those released from prison, will the Government of Guatemala or the Government of the United States publish it?

On the previous occasion it was the Government of Nicaragua who made it public and we expected a similar procedure. Why? Because there is a concern for the families and friends, about who the 135 are. There will be concern, there will be anguish, and to us, the best thing to do would have been that publication.

The United States has not published it and I do not know when it will. And in our case, we have the commitment not to publish it. Obviously we had the list from the beginning, we had the explanation almost case by case, of who these people were, but the commitment is not to make it public. This is something that I personally regret... And it is also striking that such an important fact has not been published by the Nicaraguan Government. It is a news that has had repercussions everywhere except internally, as a news issue by the Nicaraguan media.

For now, the 135 exiled Nicaraguans are in a migratory limbo. What does Guatemala offer them?

As Nicaraguans they are part of the CA4 scheme. They do not have any migratory limitation to be in Guatemala. What was done, due to the particular situation, was that the Guatemalan Institute of Migration extended them a temporary humanitarian visa for 90 days, perfectly renewable. So there is no migratory limbo for them, they have all the support of the Government (of Guatemala) and the documentation they require. What we are trying to facilitate and support is a process that is more in the hands of the United States. We know that a good number, the majority of the 135, wish to move to the United States. Guatemala has open doors if some wish to stay. Also, they have the possibility of going to a third country. So, the possibilities depend on their interests, where their families are and where they want to continue a new stage of life.

Which other countries do they have alternatives to go to with the Safe Mobility program?

I don't have a list, but I would say that the scenario is open. The program provides those facilities. As you rightly point out, it is the Safe Mobility program, which presents a range of options that is a little more open than other types of programs.

How long will they receive humanitarian assistance, lodging, and food in Guatemala?

As long as necessary. Obviously, we want to speed up the process based on their needs, so that the entire migration procedure that needs to be done, primarily with the United States, goes smoothly, which is also their commitment [of the US]. The United States offered us this urgency because we see it as essential. So, the maximum deadlines are 90 days, which are perfectly renewable. What would we like? That in just a few days, a couple of weeks at most, the first people start gradually moving.

Has there been any evaluation of the health condition of the group of 135 Nicaraguans?

From day one. When they were received at the Air Force, it was at the Returnee Care Center. It is a center where, for example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Health, the Guatemalan Migration Institute, and the Social Welfare Secretariat converge.

In this case, the health evaluation was immediate. We had more personnel from the Ministry of Health deployed than usual, specifically to assess if there were any health issues. We did not receive any reports about the health status of the 135 individuals beforehand. For those who need it, psychological assistance is also available. We offer support from all possible fronts to ensure their stay is as good as possible under the circumstances. There is support on all possible fronts, so that their stay is the best possible under the circumstances.

What impact does this measure, this humanitarian assistance provided by the Guatemalan government, have on diplomatic relations with the Nicaraguan government?

I would hope it doesn’t have a negative impact. I believe both governments are simply fulfilling their roles. We are in a position of being a receptive and open government for Nicaraguans. I would expect there to be no negative reaction. We maintain open relations and participate in regional platforms, such as SICA, and we don’t view this as a government-to-government confrontation but rather as humanitarian assistance for Nicaraguan nationals, trying to help them in any way we can.

Your government has been vocal in criticizing the authoritarianism in Nicaragua, specifically that of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo. How would you define the current state of diplomatic relations between the two countries?

I would say they are distant at the moment. President Arévalo has been very clear in his characterization of the Ortega-Murillo regime. Guatemala, especially in the past 13 months, has firmly committed to democracy. There are principles that are non-negotiable. There are commitments a state must uphold toward another, and in this case, it’s clear what President Arévalo’s position has been. For example, when he toured SICA countries, he did not visit Nicaragua, and they were absent at the January 14 inauguration. These events clearly illustrate our stance, which the President explains even more explicitly than I can.

At the last meeting of foreign ministers, Guatemala refused to support Ortega's push to appoint Valdrack Jaentschke as SICA’s Secretary General, who is now Nicaragua’s Foreign Minister. Will the SICA Secretary General position remain vacant?

At the last foreign ministers’ meeting, I made it very clear that we are in this situation because of Nicaragua, not because of the other countries. Two years ago, an agreement was reached to select the previous Secretary General, and you know the rest of the story. In recent months, during the discussions at the last ministers' meeting, Guatemala voted, along with two other countries, for one of the candidates from the slate of names Nicaragua presented. Every country evaluated the candidates, and our decision, like that of the other two countries, including Nicaragua, resulted in a split, an abrupt end to the meeting, and now we await a new proposal.

Was it abrupt because there was no consensus?

It was abrupt because we were still talking, and then suddenly, the meeting ended. The abrupt part was that perhaps they didn’t expect some countries to choose other candidates. Now, Jaentschke is the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and as Guatemala’s Foreign Minister, I will work with him, just as I worked with Denis Moncada and will work with whoever is in that role. Personally, I have no issue with him or anyone else.

But going back to that moment (the foreign ministers' meeting), a decision was made. Perhaps they didn’t understand that Guatemala and other countries were choosing someone from the slate Nicaragua presented. If the regime had already decided on one of the names, that’s another story, but when you’re presented with a list, you choose.

What’s missing for the candidates to reach a consensus?

A little bit of everything. Of course, experience in integration is fundamental, but other key aspects include a commitment to a regional vision, a willingness to put the region and SICA countries above national interests, to name just a few elements.

In an interview with El País, President Arévalo said that the lack of democracy in Nicaragua affects all of us. How does the situation in Nicaragua affect Central American integration?

Returning to the issue of the Secretary General selection, the impact is that we haven’t been able to elect one. Before selecting Werner Vargas, we spent over a year looking for a candidate for the Secretary General position. While everyone recognizes that, per the 2016 agreement, the role belongs to Nicaragua, the country hasn’t presented a slate where the other nations feel comfortable choosing a candidate. Before selecting Vargas, we went through a couple of slates where the right candidate wasn’t found. So, yes, it has an impact, not just around the Secretary General role, but on all of SICA's institutional frameworks. However, some sectoral councils, like COMIECO (the Council of Ministers for Economic Integration), continue to function. They still meet, particularly because inter-regional trade was the thread that held integration together during the crises and wars in Central America in the 70s and 80s. The exchange dropped, but never ceased. And the regulatory body, in this case, the ministers of economy, always met. So, while other areas of the process are affected, when there is a need to move forward, the ministers of economy meet.

Does Nicaragua's situation affect democracy in the region, especially in Central America?

I would say there is an impact across Latin America and within Central America. We see, with concern, a deterioration in democracy, democratic institutions, and respect for human rights. This is a phenomenon, or rather a ghost, that unfortunately haunts Central America and the rest of Latin America. It is deeply troubling.

This article was published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff. To get the most relevant news from our English coverage delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to The Dispatch.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996. Inició como un semanario impreso y hoy es un medio de referencia regional con información, análisis, entrevistas, perfiles, reportajes e investigaciones sobre Nicaragua, informando desde el exilio por la persecución política de la dictadura de Daniel Ortega y Rosario Murillo.

PUBLICIDAD 3D