Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

The Spanish spoken by immigrants who move to Uruguay contrasts with the one spoken by its inhabitants, which leads to culture shock and discrimination

Flickr.com | Creative Commons

Chilean writer Roberto Bolano believed exile is a “voluntary act”, however, ironically, it can also be an unwanted act. Anyhow, once we are placed in the “new world”, the codes we carry in our suitcase unpack themselves as a language that natives find strange.

In Montevideo, Uruguay’s capital, the most important immigrant groups speak Spanish. Most come from Venezuela, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, as well as other smaller Latin American diaspora communities.

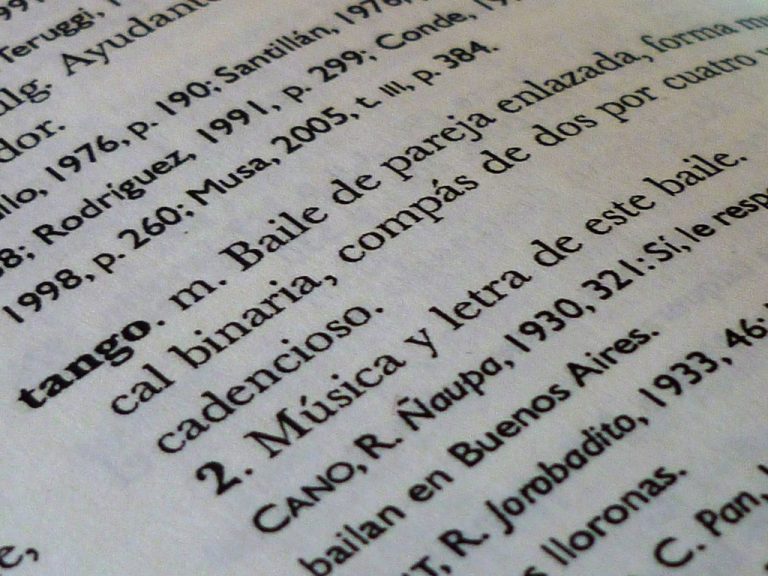

Spanish is the second most spoken language in the world, after Mandarin and ahead of English, Hindi, and Arabic. It is spoken in over twenty American countries. Its historic process continues to be dynamic, and as Nicaraguan writer Sergio Ramirez puts it, Spanish: “Knows how to enter new mixes, because it thinks of itself as the fruit of a permanent hybridization throughout History.”

This language that becomes hybrid, driven by past and present, continues to migrate with the region’s political upheavals. Experts say there is an entire country of Venezuelans in exile, almost five million people or more. There are also hundreds of thousands of Cubans moving everywhere. Since 2018, almost 100,000 Nicaraguans have fled violent social unrest and the dictatorship’s subsequent repression.

With this displacement, millions of people are reconfiguring our continent’s linguistic geography. This isn’t to say it’s a sweet and nice process though. Instead, it stirs a big melting pot of preconceptions and stereotypes that exacerbate discrimination.

In a country like Uruguay -which hadn’t received significant waves of immigration since the end of World War II and where its culture is founded upon an idiosyncrasy of European traditions -, the Spanish that emigrates contrasts with the hegemony of Rio de la Plata’s Spanish. This leads to cultural shocks and discrimination based on “linguistic supremacy of Rio de la Plata Spanish.” The latter believes that “others” aren’t “speaking the language properly”.

The concept of a nation-state, as a political space and cultural identity, tends to lean towards homogenization. Such is based upon a narrative charged with collective imaginations and myths that make up what we call “national identity”. In today’s globalized world, convulsive and migrating, these concepts turn into dangerous stories. It becomes a must to reject anything different, because they “threaten” national identity and, in this case, linguistic identity.

In Uruguay, the story of a country without indigenous peoples, of being direct descendants of the Spanish and Italian, and its long-standing tradition of democracy and institutionalism, has meant that its people don’t identify with Latin America and feel closer to Europe instead. This has led to stereotypes about “Latin Americans”. However, today, the polyphony of accents can be heard on Montevideo’s streets, more and more.

Different canticles and odd words are called into question. Rejection is still unspoken; it’s quite hidden. However, the scent given off by this concentration of foreigners is beginning to make locals feel uneasy. They seem to ignore the fact that Spanish is taken from loaned linguistics, neologisms, hybrids, Spanglish that knocks on the door, and sits at the table in Mexico, Central America, and other countries in this subcontinent.

On social media, there is some hate speech asking for Venezuelans and Cubans to return to their countries. Dominicans are discriminated against more openly, as they are poorer and darker-skinned. They also bring a misunderstood joy with them to the city of Benedetti and Galeano.

Merengue echoes in some neighborhood streets, which have become ghettos of Dominicans. Many Montevideo natives don’t accept these expressions and differences, so they move to more southern districts.

The historic center, a district that is positioned on Montevideo’s port shore, receives the new immigrants. You can hear tropical sounds and strange accents in this neighborhood. Also, grammatical constructions that are different from Rio de la Plata’s sentences. Uruguayans find this language unintelligible and Montevideo locals believe that they are speaking poor Spanish.

It’s hard to understand in a society that is so markedly European, that this Antillean Spanish mixed with the black voices of slaves and Taino Indians, this island Spanish, with a disturbing and annoying sound, is proper.

This phenomenon has had a blunter impact on the labor market. Many of these immigrants have joined the labor force. Uruguay is a country with just over three million inhabitants, with one of the lowest birth rates in the continent. It’s an aging country, with few young people and a high rate of youth emigration to Europe or the US. This presents opportunities to the many young immigrants who arrive, many of whom have degrees.

This South American state refuses radical change, its processes are slow and conservative. The same thing is happening with speech. While the rest of Latin America is incorporating English words, mainly, or trending words from Iberian Spanish or other cultures; in Uruguay, even synonyms that could be used to legitimately replace other words and grammatical structures that are habit and unharmed in this southern region, are frowned upon.

For example, the word espléndida (splendid), used by a Venezuelan friend in a Facebook post to describe “a bookstore where book X was presented”, was censored. This has to do with this society’s firmly rooted cultural constructions. The use of “grandiose” adjectives, such as espléndido, are not commonly used in the Uruguayans’ frugal speech. They save on adjectives, as their culture doesn’t allow for praise, it is frowned upon and considered unnecessary flattery.

In my personal experience, I sent an email once and was told “I should save this Central American smooth talk”. However, it was grammatically correct, the syntax acceptable, it was clear and made the email a lot more friendly. Doing so without undermining the message that it needed to transmit.

Exile brings with it the need to self-censor your own personality. Both body language and the words that are let out from our mouths give us away as foreigners. Then we become a target for discrimination.

Language is unity, but also opposition, even within the same language, as it must deal with regional differences. Migrating within Latin America does not mean that we all speak the same. Or that we will be considered the same just because we speak Spanish. Linguistic variants reclaim their own supremacy, which becomes a disadvantage that those who don’t belong, end up fighting.

However, the people who are really missing out are those who receive guests in their homes with other world views and don’t know how to make the most of them to enrich their culture. I wonder what it was like when the Italian and Spanish came to these lands. Were they received with greater pleasure and their customs assimilated quicker, than these new mestizo immigrants, in race and language?

A country without indigenous peoples, without a millennial past, needed to construct an identity. It clung to the Mediterranean white people, who had to immigrate to South America because of the tragedy of war.

Now, another war, of populist dictatorships in the banana republics, is displacing the non-European and Mediterranean prototype to these Uruguayan lands, which still don’t understand that it belongs in Latin America. This, despite its people clinging onto an immigration past that will never come to be again.

Maybe, this bold statement can be backed up by the xenophobic and racist song No somos latinos (We aren’t Latinos), by the Uruguayan rock band El Cuarteto de Nos. In some verses, it says: “These idiots want me to believe, that we Uruguayans are Latinos… Don’t fuck around, we aren’t Latinos. I was raised here in the Switzerland of the South.”

*Victor Rodriguez is a Nicaraguan social communicator and cultural manager currently residing in Montevideo, Uruguay.

This article was originally published in Havana Times.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D