9 de diciembre 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

A fund of over $500 million finances agricultural, commercial, and real estate ventures tied to the Ortega-Murillo family and their associates

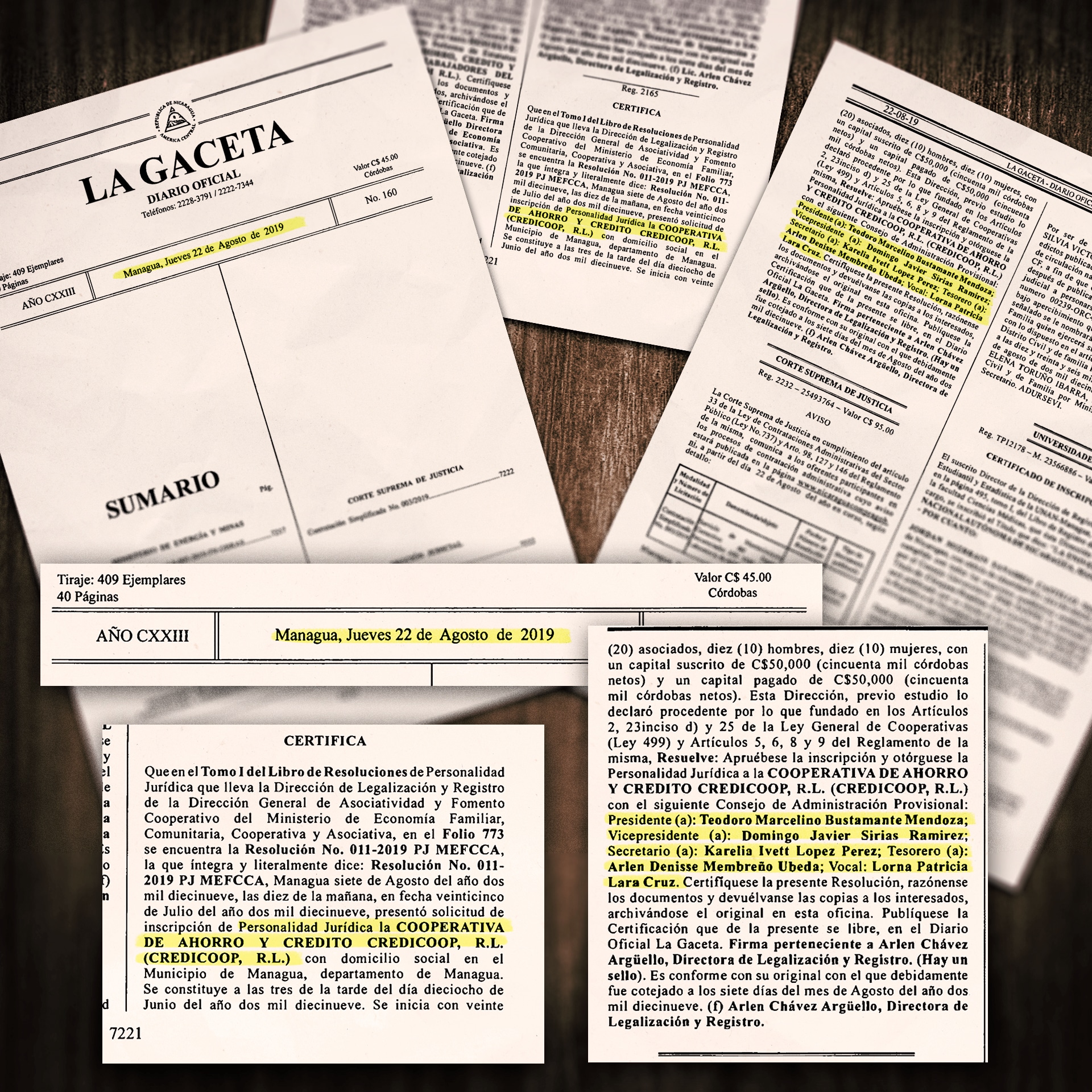

Credicoop is a financial entity created in 2019 to evade international sanctions on the Bancorp and Caruna // Photo credit: CONFIDENTIAL

Two months after the 'voluntary dissolution' of the Banco Corporativo (Bancorp), which was sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury in June 2019, the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo ordered the creation of a new entity called the Savings and Credit Cooperative (Credicoop). Its purpose is to evade international sanctions and 'launder' more than 1.8 billion córdobas (approximately $49.3 million) from Bancorp’s loan portfolios and the Alba Caruna financial institution, sanctioned in 2020. These resources are then funneled into the private businesses of the Ortega-Murillo family and their associates.

Credicoop’s main office is located in the Delta Building, across from the Teresiano School on the Masaya Highway. It had two branches: one south of the Linda Vista traffic lights (also in Managua, which closed in September), and another in San Carlos (Río San Juan).

Credicoop offers public services such as loans for purchasing new or used vehicles, repairing or building homes, as well as personal, agricultural, SME, and business loans.

Credicoop’s main activity, however, is financing the private businesses of the political and military elite in power. These businesses are managed through a network of frontmen who purchase coffee, livestock, agricultural, poultry, rice, and commercial properties across Nicaragua. These funds originate from Venezuelan state cooperation, which was illegally privatized.

Credicoop also acts as a lender to various state entities in Nicaragua, with the backing of the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, which later repays the loans. It also finances projects for municipal governments, imports for the Nicaraguan Institute of Social Security (INSS), and purchases for the Penitentiary System or the National Police stores, which are later covered with funds from the National Budget.

Additionally, it operates an ATM that provides access to the MIR payment service ('mir' in Russian, meaning 'peace'), although international sanctions imposed on this system have significantly limited its options.

On April 17, 2019, the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned Laureano Ortega Murillo, the son of the presidential couple, and Banco Corporativo (Bancorp) 'for their roles in the corruption network and money laundering benefiting the Ortega-Murillo regime' and for financing repression. At that time, Bancorp managed assets worth 5.783 billion córdobas (approximately $158.7 million) and a loan portfolio of 1.644 billion córdobas (approximately $45 million), with the majority (72.5%) dedicated to commercial activities, and smaller percentages allocated to agricultural, industrial, and livestock sectors.

The first reaction of Ortega and Murillo was to try to have the state purchase Bancorp and convert it into an entity that would be called Banco Nacional. However, that strategy failed, as the surface-level change was not enough to protect against new sanctions. Instead, they simply discarded the plan, opting for a different approach.

At 3:00 PM on June 18, 2019, the Savings and Credit Cooperative (Credicoop R.L.) was established in Managua, consisting of 20 members (10 men and 10 women), with a subscribed capital of 50,000 córdobas (approximately $1,370) and paid-in capital of the same amount.

A month later, on July 25, they submitted a request for registration of their legal status to the Ministry of Family, Community, Cooperative, and Associative Economy (Mefcca), a key ministry of Rosario Murillo, now reduced to a symbol of Ortega's corruption.

The request was approved through Resolution N 011-2019 PJ MEFCCA at 10:00 AM on August 7, 2019, as published in La Gaceta Diario Oficial, edition 160, on August 22, 2019.

One year later, on October 9, 2020, the U.S. Department of the Treasury also sanctioned the Savings and Credit Cooperative Caja Rural Nacional RL Caruna, which operated as a financial institution managing funds from Venezuelan cooperation. The financial system forced Caruna to close its accounts in private banks, and its millions in resources were also transferred to increase the capital of Credicoop.

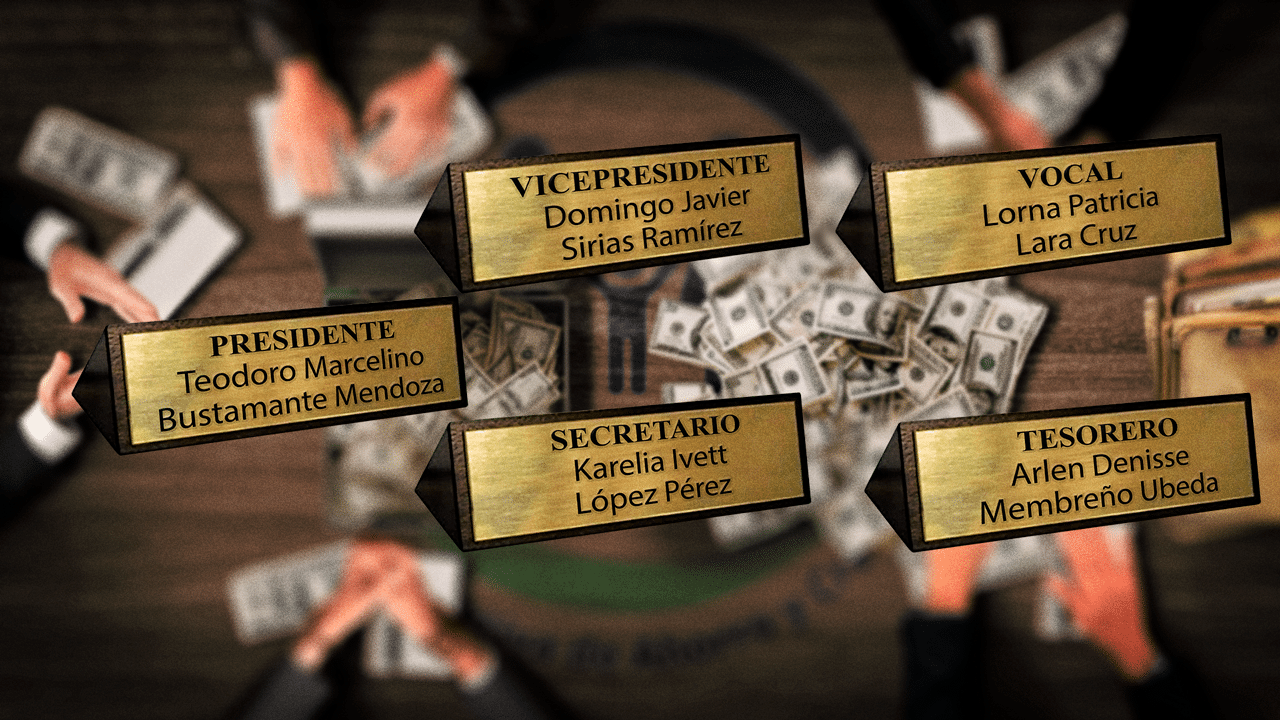

Credicoop was established with a board of directors led by retired Commissioner Teodoro Marcelino Bustamante Mendoza, a former administrator of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing at the now-defunct Banco Corporativo (Bancorp) and the former deputy head of the National Police’s Institute of Criminalistics and Forensic Sciences, who was sent into retirement in 2014.

Alongside Bustamante, Domingo Javier Sirias Ramírez serves as vice president. Sirias, an accountant, is a former collaborator of the also-sanctioned Caruna and acted on behalf of Francisco “Chico” López, treasurer of the Sandinista Front, vice president of the likewise-sanctioned Alba de Nicaragua S.A. (Albanisa), and a business operator for the dictatorial family.

Bancorp was created to replace Caruna as the financial arm of Albanisa. This decision came after an audit by the Venezuelan counterpart revealed numerous irregularities in the management of joint funds held in private banks in Nicaragua. The findings prompted the creation of a bank where they could exercise greater control.

“The presence of Bustamante and Sirias on Credicoop’s board makes it clear that this institution is a continuation of Bancorp,” says Nicaraguan economist and former political prisoner Juan Sebastián Chamorro, who was exiled by the Ortega-Murillo regime.

Credicoop’s organizational structure includes Arlen Membreño, head of Administration and Human Management, who is the daughter of General Denis Membreño, director of the Financial Analysis Unit (UAF).

It also includes Norma Lara, who was part of López’s team at Albanisa, and Karelia López Pérez, who previously worked at Caruna.

The management team consists of two executives who operate independently within the organization to ensure dual oversight of its interests—one acting on behalf of retired General Óscar Mojica and the other representing Francisco “Chico” López, two trusted figures of the Ortega-Murillo family.

The first is Óscar Mojica Aguirre, former Credit Manager at Bancorp and son of retired Major General Óscar Mojica Obregón, who currently heads the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure and oversees the Urban and Rural Housing Institute (Invur).

In the early 2010s, Mojica Aguirre served as the executive president of Viviendas Económicas de Nicaragua S.A. (Vienicsa, Affordable Housing of Nicaragua), which, along with Tecnosa—a company owned by Francisco López—profited from Venezuelan funds for social housing projects. In February 2013, from his position at Vienicsa, Mojica Aguirre requested $1.3 million from the Alba Investment and Finance Commission. He is also listed as the owner of the company that built the Valle de Sandino housing development, managed by Caruna, where homeowners later reported irregularities in their monthly payments.

The second is Bernardo Aráuz Mayorga, a trusted associate of Francisco “Chico” López in Albanisa and legal representative of Agronegocios Comerciales. This shell company, presided over by private businessman Tirso Celedón Lacayo, was used by the Ortega-Murillo family in 2013 to acquire the state-owned electricity distribution companies Disnorte and Dissur, valued at $140 million, as revealed in a CONFIDENCIAL investigation published in June 2024.

Credicoop’s executives “laundered” vast amounts of cash originating from the sanctioned Bancorp and Caruna using a mechanism designed to assure banks they could receive the funds without risking new U.S. sanctions.

How did they do it? “I’ll answer you with one word,” a financial expert told CONFIDENCIAL, speaking on condition of anonymity. The expert then added: “Trusts.”

This arrangement or contract, which serves to transfer ownership of specific assets or rights, was described by the same source as “a financial engineering invention often used for money laundering.”

In Nicaragua, the concept of a trust allows an entity with legal personality—such as a foundation, association, cooperative, or individual—to act as the trustor and provide an amount to the trustee, in this case, private banks within the financial system. The trust specifies how the funds will be used and who will benefit from the profits.

“It could involve money, real estate, purchasing commercial, residential, or productive properties, leasing vehicles... anything!” the source explained.

Meanwhile, the trustee—typically a private bank fully aware of the funds’ origins—earns a commission for managing them.

In theory, the bank is obligated to investigate the source of such large sums of money. However, the shield employed was the claim that the funds came from the “voluntary dissolution” of Bancorp, leading the banks to believe there was no reason to question their origin.

Since its creation in 2019, Credicoop’s resources have been used to finance businesses and purchase properties, taking advantage of the lack of transparency in how the Public Property Registry operates.

“In addition to funding private businesses owned by the ruling family, they also finance ventures of some Army generals involved in large-scale timber operations. They’ve purchased large cattle ranches in Siuna, Rosita, San Miguelito, and Río San Juan, as well as properties for certain Police commissioners and senior political operatives of the regime,” a source connected to the productive sector told CONFIDENCIAL.

They also allocated six million dollars to purchase Agroexport, a seized bean processing and exporting plant that owns the Blanditos brand in Matagalpa, previously managed by imprisoned former Treasury Secretary Juan José Montoya.

Credicoop financed the purchase of land between Sébaco and Matagalpa to establish dry coffee processing facilities, as well as 20 coffee farms in Matagalpa and Jinotega. Additionally, they acquired ten cattle ranches covering over 10,000 manzanas (approximately 17,200 acres) with thousands of head of cattle in Waslala, El Naranjo, and Siuna. Other acquisitions include a poultry company in Estelí and dozens of houses for commercial use in that city, all of which were seized by the Attorney General’s Office.

Sources connected to the private sector also report that in the real estate sector, Credicoop finances joint ventures with the Institute of Military Social Welfare (IPSM), the public investment fund of the Nicaraguan Army.

Among these is the construction of Casas para el Pueblo (Houses for the People), with price ranges between $25,000 and $35,000, driving a project of over 3,000 homes located on the New Highway to León.

Credicoop has also purchased portfolios of highly indebted companies from private banks, either to strengthen its financial arm or to venture into agricultural, industrial, and agroindustrial businesses.

One example is the purchase of the debt of Agrícola Santa Lastenia, owned by the brothers Emiliano and Abelardo Henríquez in Malacatoya, which spans more than 3,000 manzanas (approximately 5,100 acres). This company was dedicated to melon exports and the planting of over 2,000 manzanas of irrigated rice per cycle (which amounts to 4,000 manzanas annually).

The family-owned company owed nearly $20 million to Banco LaFise, but Credicoop acquired it for $10 million, providing $6 million in working capital. In this arrangement, the Henríquez brothers manage the productive farm, but under the control of a trustee who oversees the purchase of supplies and the commercialization of the rice, according to a food industry businessman who spoke to CONFIDENCIAL.

Credicoop's funds are also behind the failed operations to purchase two fresh fish export plants, as well as the financing of the closed cattle slaughterhouse in El Rama, owned by Albanisa.

Credicoop's business includes carrying out operations backed by funds from the General Budget of the Republic, as occurred between the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022.

“They decided to bypass the budget, the mayors, and the Ministry of Finance, with loans to finance projects that are relatively large for municipalities, so they couldn't be funded solely with their annual budget allocations,” explained a professional familiar with how the state was involved in this operation.

“The goal is to leverage the municipalities, while trying to use that cash and launder it through budgetary allocations. I'm not sure if the Ministry of Finance directly pays Credicoop, or if it does so through some other account,” they added.

Using a similar scheme, they also finance companies that import medications, eyeglasses, and other goods for the Nicaraguan Social Security Institute, as well as the supply of food to the country’s prisons and police stores, where they supply the basic basket for about 20,000 officers every month. This operation supplies nearly 20,000 quintals of rice, 10,000 quintals of beans, along with oil, sugar, coffee, corn, and other products to the penitentiary system and stores.

Credicoop also provides loans to Concreto y Más, the company linked to the powerful Secretary General of the Managua City Hall, Fidel Moreno, and builds the “Streets for the People,” managing operations with the municipalities.

Additionally, they finance the Saba Pharmacy network, which reaches almost every municipality in the country with over 200 pharmacies linked to Gustavo Porras, and a network of pawnshops and loan services—many of which provide cash loans—associated with Laureano Ortega.

On January 10, 2007, then-president of Venezuela Hugo Chávez signed an agreement with Daniel Ortega for Nicaragua to join the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Latin America (ALBA), which created a cooperation scheme based on the acquisition of Venezuelan oil under favorable credit conditions.

As a result of this, the regime received over $4.5 billion over the course of a decade. The ruling family used these resources to create a business conglomerate, which included electricity generation, fuel importation and distribution, road and housing construction, machinery rentals, public transportation, among others.

The millions of dollars from Albanisa, the company created to manage the business, were initially handled in private banks through Caruna accounts, the financial arm of Alba. They were later transferred to the Banco Corporativo (Bancorp), created by the dictatorship to manage its funds. But after being sanctioned and subsequently liquidated, the funds returned to private banks in accounts or trusts under Credicoop.

The series of sanctions initiated by the U.S. government in 2019, and later replicated by the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland, severely impacted the regime's ability to invest its resources, especially when Bancorp itself was sanctioned, which by then was managing a trust that could not be deposited in any bank or microfinance company in the country.

Until they created the cooperative Credicoop, which operates as the “petty cash” for the Ortega-Murillo clan to finance the family business and those of their associates, with a capital of $500 million.

This article was published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff. To get the most relevant news from our English coverage delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to The Dispatch.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996. Inició como un semanario impreso y hoy es un medio de referencia regional con información, análisis, entrevistas, perfiles, reportajes e investigaciones sobre Nicaragua, informando desde el exilio por la persecución política de la dictadura de Daniel Ortega y Rosario Murillo.

PUBLICIDAD 3D