5 de noviembre 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

In the Darién, they face death, and beyond the jungle, Central American governments “shift the responsibility” to get rid of them as soon as possible

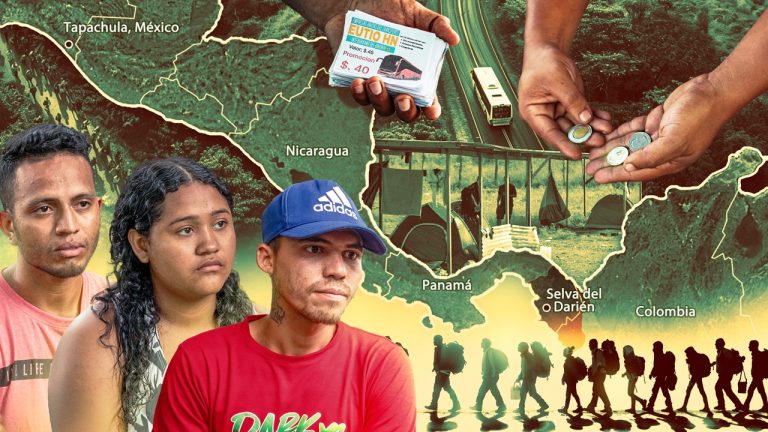

Photo art: Nicas Migrantes | CONFIDENCIAL

Migrants who make it across the Darién Gap continue along a so-called “humanitarian corridor” through Central America, where governments appear to “pass them along” to get rid of them as quickly as possible. After surviving the jungle, they face xenophobia, inhumane treatment, and a system in which many try to profit from them as they chase an “American dream” in the United States—only to find those doors closed to them as well. A Nicas Migrantes team from CONFIDENCIAL followed a group of migrants through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Honduras, on a journey marked by opportunism and indifference that drains them of every last dollar they have.

“We need help to rescue a young man here in the Darién! His name is Arman Miguel, Ecuadorian, from Santo Domingo,” pleaded José Luis González, a Venezuelan migrant who, on his journey to the United States, found the man abandoned in critical condition in the Darién, a jungle and swamp area frequented by migrants.

González recorded a video showing Arman’s condition and ID card, hoping to contact his family for a possible rescue. But Arman died in the jungle the next day.

For González, this was just one of many tragedies he left behind on one of the world’s most dangerous migration routes, stretching from the southern tip of the Americas to the north and through the Darién. This natural barrier between Panama and Colombia has become a deadly corridor for migrants from across Latin America and beyond, escaping poverty, violence, and lack of opportunity in their home countries.

In early October 2024, a Nicas Migrantes team from CONFIDENCIAL contacted González at Costa Rica’s southern border, just as he was beginning his journey through Central America. He was one of several migrants who agreed to be interviewed and keep in touch throughout the route across the isthmus, helping document the experiences of tens of thousands who, like him, travel thousands of miles overland in hopes of reaching the United States for a better life. This report follows migrants on their passage through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Honduras.

González is asking for Arman’s video to be shared so his family can receive the news, though his full name and details aren’t clearly visible.

In recent years, the United States has seen record numbers of migrants arriving at its southern border seeking asylum. In 2023, the record figure reached more than 2.4 million migrants, including hundreds of thousands who had crossed through the Darién.

In response, since June 2024, the United States has drastically restricted asylum applications at the border with Mexico. Additionally, U.S. authorities have arranged with Panamanian officials to establish flights for deporting migrants from Panama who are en route to the U.S.

Over 400,000 people crossed the Darién in 2023, tripling the 133,000 who did so in 2022, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Between January and October 2024, Panama's immigration authorities reported 264,496 irregular entries through the Darién jungle, representing a 36% decrease compared to the same period in 2023, when 410,962 entries were recorded.

Manuel Orozco, a Nicaraguan researcher and director of Migration, Remittances, and Development at the Inter-American Dialogue, attributes this decline to restrictive measures by countries and a lower number of young people in a position to undertake the journey from their home countries.

There’s no time to rest. Upon arriving in Bajo Chiquito, the first Panamanian town after the jungle, José Luis González immediately begins his journey through the Central American isthmus. Authorities instruct him to pay $60 to take a bus to Costa Rica. From there, he will board another bus heading to the Nicaraguan border.

The so-called “humanitarian corridor” between Panama and Costa Rica aims to organize and manage the significant flow of migrants, transporting them from Panama to the Nicaraguan border in a sort of express route.

At Paso Canoas, the southern border of Costa Rica, González shares how the journey to that point went. “I’ve been traveling for almost 16 hours. We left Panama at three in the afternoon and arrived here (Paso Canoas) around six or seven in the morning, where they are now asking me for another $30 to keep using this service,” González explains, referring to the logistics implemented since October 2023 by the governments of Costa Rica and Panama.

The Temporary Migrant Assistance Center (CATEM), located in Paso Canoas, is where migrants switch buses. Every day, around a thousand people, mostly Venezuelans, pass through CATEM.

José Pablo Vindas, the coordinator of the Brunca Region for the Professional Migration Police in Paso Canoas, explains that the collaboration between Panama and Costa Rica allows for a more organized arrival of buses from the Darién, making it easier to register and monitor migration flows. “Before, we had to search for migrants on the streets or at bus terminals, but now, with more controls, we can collect data more accurately,” Vindas notes.

Before the migrants arrive in Paso Canoas, Panama’s authorities share lists of the migrants and their buses with Costa Rica to check their judicial and police records.

“We receive the list the day before, which lets us filter through our systems and identify if anyone has a criminal record or international arrest warrant,” Vindas adds. According to the Costa Rican Directorate of Migration and Foreign Affairs, since the humanitarian corridor was created in October 2023, 418,500 migrants in transit have entered CATEM. So far in 2024, 274,502 people have come through, with 69% being Venezuelan.

Inside the CATEM in Paso Canoas, Costa Rican authorities provide humanitarian assistance to migrants in coordination with NGOs and UN agencies.

“We offer medical assistance, psychological support, and other services, but for migrants, the top priority is mobility. Sometimes they turn down help because all they want is to continue their journey,” says Vindas, highlighting the challenge of balancing humanitarian aid with migration control and the need to move groups of migrants quickly.

However, migrant rights organizations, such as the Jesuit Migrant Service (SJM) in Costa Rica, criticize the approach and priorities of the authorities.

Roy Arias, the SJM’s Borders Coordinator in Paso Canoas, argues that the process feels more like a government effort to “hand off responsibility,” rather than a genuine attempt to meet migrants' needs.

Roy Arias

Border Coordinator for the Jesuit Migrant Service in Paso Canoas

Many migrants arrive (from Darien to Paso Canoas) sick or traumatized, and are not given the time they need to recover before continuing their journey.”

The coordinator of this NGO for migrants criticizes that “the corridor is managed with police and military criteria, not humanitarian ones, admitting people and telling them: ‘You just arrived here, you have to leave.’” For Arias, this policy leaves migrants more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse by unscrupulous individuals.

At the CATEM, González, along with other Venezuelan migrants like Wuider Gallardo and Jeampier Vargas, are calculating whether to continue their journey to Nicaragua. Not everyone has the $30 needed for the fare.

“We travel in groups, and if one of us doesn’t leave, the rest of us don’t go either,” comments Vargas, who is traveling with five adults and three children. Gallardo, for his part, is with his wife, two children, his sister-in-law, and a friend. They arrived the day before but didn’t have enough money for the tickets, so they spent the night sleeping at CATEM.

The next day, Gallardo withdrew money sent by his family through a remittance agency located at CATEM and was able to buy the tickets. They registered for the 9:10 a.m. bus.

González and part of Vargas's group received “courtesy passes” that are distributed twice a week. “We have several methods to help people move forward,” Vindas points out. “One is through the ‘courtesy tickets,’ another is through transport companies that donate two trips per week to migrants, and sometimes, when there are too many people, the Migration Police use their own buses, although that isn’t always possible,” adds the Paso Canoas Migration officer.

“We were given an exception because we didn’t have the $30 to pay for the fare, and they told us they would seat us there, all squished in the aisle,” says González, who traveled with an elderly person and five others, all sitting on the floor of the bus during the ten-hour journey.

According to Arias from the Jesuit Migrant Service, the buses used in the humanitarian corridor have serious deficiencies and lack adequate conditions for long journeys. “It was made clear that the mechanism is funded by the governments, but it is private contractors that provide the service, and it is the migrants themselves who pay for it with their own resources,” he emphasizes.

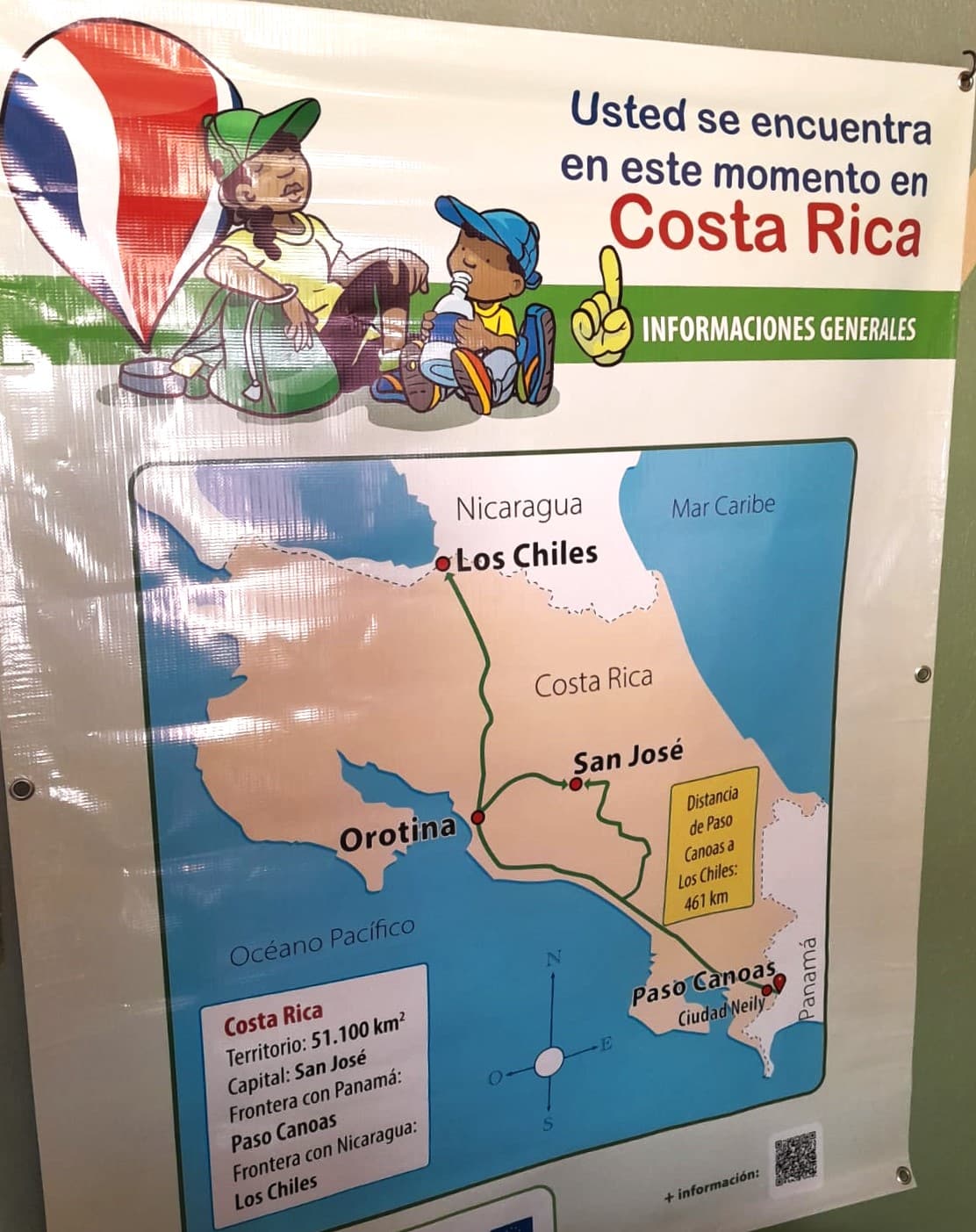

Migrants travel 461 kilometers between Paso Canoas and Los Chiles, with two stops: one in Uvita, Puntarenas, 135 km from Paso Canoas, and another in Orotina, Alajuela, 303 km away // Photo: Jesuit Migrant Service.

The Nicas Migrantes team from CONFIDENCIAL followed one of the buses on its route and observed that, during the journey, it made two stops where migrants used restrooms and bought food. Some drivers inform the travelers where to spend the night, but Arias points out that not everyone does so in good faith.

“Migrants receive misleading directions from drivers, who collaborate with groups looking to profit from their situation,” warns Arias.

After 13 hours of travel, González and Vargas arrived in Los Chiles, a border town with Nicaragua, where they were immediately approached by lodging owners who transported them in vans or minibuses. Among them were also human traffickers, according to Sofía Donzón, director of the organization Manos Amigas, which provides food to migrants in transit at the Los Chiles terminal.

“Coyotes take advantage of migrants by ‘making deals’ with bus drivers; some take them to hotels, promising to get them across to Nicaragua,” she explains. Others, who do not have money, remain at the terminal for weeks until they manage to gather enough to continue their journey, adds Sofía Donzón from Manos Amigas.

“In Costa Rica, the treatment is really good, it’s great,” González says gratefully, but Vargas cuts in: “Well, they arranged transportation for us because they don’t want us to work anymore; they don’t want to see us around. We can’t work anymore because I was told that in Costa Rica, you could earn some money and make progress. But that’s not the case anymore; we have to leave right away,” he complains.

By the end of 2022, before the “humanitarian corridor” was established in Central America, dozens of Venezuelans began wandering through San José and other cities in Costa Rica. Many Venezuelans stranded there reported being charged $150 by the Ortega Administration in Nicaragua for a supposed “safe conduct” pass, which is a document that allows migrants to transit through the country legally. Not having that money prevented them from moving forward in their journey.

On social media, there were xenophobic comments and complaints about the plight of Venezuelan migrants stranded in Costa Rica, who were seeking temporary jobs or selling goods at traffic lights. According to authorities, there was also a rise in crime in some areas of the capital linked to the presence of migrants. Today, there are few Venezuelans visible on the streets.

After spending the night outdoors, Vargas, González, and Gallardo hurry to continue their journey to Nicaragua, a country with no official plan for managing or providing humanitarian assistance to migrants.

“Entering Nicaragua is like stepping into a black hole, where the situation completely disappears,” comments Arias from the SJM. “They are at the mercy of a dictatorship and the 'businesses' of the Ortega-Murillo family, as well as corrupt networks within the Army and Police.” In Nicaragua, there is no support or statistics regarding migratory flow, even though the country is also a transit route for migrants from African countries who continue to arrive through the International Airport, despite U.S. sanctions.

Vargas recounts that they were prevented from crossing at the official Nicaraguan immigration checkpoint, and instead, uniformed officials directed them to an irregular crossing point known as “Los Naranjales.”

Upon arriving in Nicaragua, they found taxis offering to take them to the terminal for two dollars for a trip of less than 15 minutes. “We were stopped by the Nicaraguan Army, who checked our documents and let us continue,” Gallardo mentions.

CONFIDENCIAL and other Nicaraguan media have confirmed, through various testimonies, that many migrants have paid the 150 dollars demanded by Nicaraguan authorities as a supposed safe conduct to move around the country, although this fee is not official. However, Venezuelans who stayed in contact with this outlet for the report, despite being approached by military personnel and Nicaraguan officials, were not asked to pay this fee.

“Venezuelans haven’t been charged for the safe conduct in almost two years, but migrants from other countries have. That’s why many try to cross the border at night,” says Donzón from Manos Amigas.

The journey through Nicaragua was uncertain and filled with obstacles. In San Carlos, the migrants paid 50 dollars to travel from the La Rotonda terminal to the border with Honduras. There is no logistics in place to assist them, despite the police presence. Migrants are left in the hands of transporters and the goodwill of citizens who give them some supplies for their journey.

During the crossing through Nicaragua, the bus did not make the promised stop for rest, and after a breakdown, they were stranded in the rain for hours. “At midnight, we were on the highway waiting for a transfer,” Gallardo recounts. In the end, they traveled standing for the rest of the journey, despite having paid for a full fare.

“It’s not fair; they packed us into a bus meant for 50 people with almost double the passengers,” Vargas comments. After 17 exhausting hours, everyone arrived at Las Manos, the border with Honduras, except for González, who remained in Nicaragua and was unable to proceed that day.

Upon arriving in Danlí, a border city, González, Vargas, and Gallardo were welcomed at the Francisco Paz Irregular Migrant Assistance Center (CAMI), where they received “meals, accommodation for one night, and medical assistance to continue their journey the following day,” explains inspector Gustavo Cárcamo. Additionally, the CAMI provided them with a free transit permit for five days to move legally throughout the country. Cárcamo clarifies that if migrants exceed this time, they incur a migratory infraction, although they can request up to two additional days in special cases.

After receiving humanitarian assistance in Honduras, González, Vargas, and Gallardo paid 40 dollars to continue their journey to Guatemala on buses coordinated by the government.

In addition to CAMI, Doctors Without Borders provides medical care to migrants in transit, addressing respiratory, skin, and gastrointestinal issues. According to Elissa Ríos, who is in charge of the mobile clinics, they also support survivors of sexual violence, treating five to seven cases daily, many of which occurred in the Darién jungle and at “Los Naranjales” in Nicaragua. Recently, there has been an increase in cases they are attending involving men who are victims of sexual violence.

González entered Honduras two days after Vargas and Gallardo. He spent the night at the CAMI and continued his journey to Guatemala the next day. According to the National Migration Institute (INM), around 300,000 irregular migrants crossed from Nicaragua to Honduras between January 1 and October 7, 2024.

González took a bus from the CAMI in Danlí to Agua Caliente, the border crossing between Honduras and Guatemala, on a 12-hour journey. “This trip wasn’t too exhausting for me because I was lucky enough to sleep in a bed in Honduras and not travel uncomfortably like on previous routes,” he said.

Near the area, there are humanitarian aid organizations that assist migrants in transit. In Guatemala City, they pay for a tour-type transport that takes them to Tapachula for $40. “They pick us up at a shopping mall, and from there, they drop us off right in Chiapas,” Gallardo mentions.

Mexico presents another major challenge for migrants. Many are unable to move forward due to various dangers such as theft, extortion, or kidnapping, warns Arias from SJM.

Tapachula, in particular, is a critical point where thousands of people are trapped, unable to move north or return south. Mexico's migration policy, described as “brutal” by Arias, has turned this area into a true bottleneck.

A week after crossing the Darién jungle, González, Gallardo, and Vargas found themselves at a migrant center in Tapachula, fearing deportation or falling victim to drug trafficking. González and Vargas are currently working irregularly in construction, while Gallardo has attempted to leave Chiapas but has been detained both by cartels and by Mexican immigration police. “We have had to pay over a thousand dollars just to try to leave this state,” he adds.

While seeking the financial means to continue their journey through Mexico and avoiding falling into the hands of drug traffickers or being deported, migrants face another barrier in the final stretch toward the United States: the restrictions imposed by that country on daily asylum applications, which could leave them stranded just a step away from their “American dream.” The future for the three remains uncertain, but they hold onto the hope that their risky journey will be worth it.

With the collaboration of Juan Daniel Treminio and Jairo Videa in Danlí, Honduras.

This article was published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff. To get the most relevant news from our English coverage delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to The Dispatch.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Nicas Migrantes es un proyecto periodístico de CONFIDENCIAL especializado en abordar temas de interés y utilidad para la población nicaragüense migrante en el mundo, principalmente en Costa Rica, Estados Unidos y España. El proyecto pionero nació en 2020 y produce contenidos en diferentes formatos periodísticos y plataformas.

PUBLICIDAD 3D