14 de mayo 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

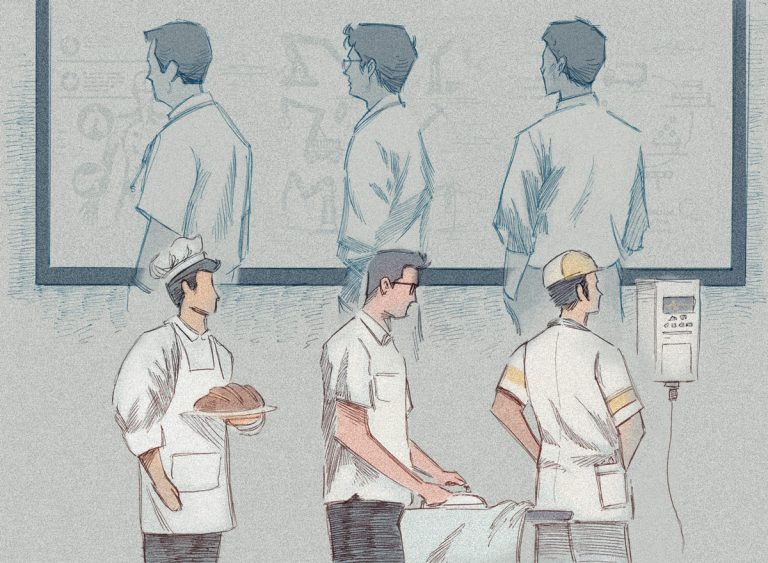

Their days in front of the classrooms in Nicaragua are over. Today they work advising monographs, baking bread, or ironing clothes in Costa Rica

Teachers expelled from Nicaragua perform work in Costa Rica for which they are overqualified.

Dismissed from their jobs or expelled from Nicaragua, hundreds of teachers have had to leave the classroom to look for new job options, inside or outside the country. CONFIDENCIAL spoke with three of them, based in Costa Rica, who agreed to tell their stories under the pseudonyms of Bradford, Karime, and Ignacio.

In addition to repressing citizens who protested in the streets demanding the end of the Ortega-Murillo regime in April 2018, the dictatorship also targeted professionals and state employees of all levels. This meant thousands of dismissals of teachers, doctors, administrators, secretaries, drivers, janitors, and others for not agreeing with the official party line.

Karime was one of them. When he graduated from Nursing in the first half of the last decade, he received a strange assignment in social service: he would have to give free classes in social studies, (a subject renamed as 'values formation'), and biology, to fourth and fifth-year students, knowing that he had to comply with the indication that the students had to pass no matter what.

If any of them failed, “we had to round up the grade to 60,” which is the minimum passing grade in Nicaragua. “That's how I became a teacher, after which they gave me a bachelor's degree certificate. When I finished the year, they gave me two more certificates, which I have kept, but I don't present them because they have that red and black flag,” said the professional.

After that teaching experience, he combined nursing with teaching at different times, seeing that his former students sought him out for private tutoring on subjects they had not passed at the university, or to help them by teaching their children.

Although he started working for the Ministry of Health (MINSA) in 2016, he did not have a formal contract until January 2018 because of his political leanings.

“I have always been anti-Sandinista, and when the municipal or presidential elections came, they would send me to vote and I did not go. I always told them what I didn’t like at the hospital. In January 2018 they gave me an eight-month contract, but as the protests began, and I participated in that, they took away that privilege,” he recalls.

Faced with the siege that followed when he openly declared herself anti-government, Karime decided to leave Nicaragua, crossing the border with Costa Rica through blind spots.

When he arrived in San José, a city he did not know, he ended up in La Merced Park, where a street vendor took pity on his situation and took him to her house. He helped out at the street vendor’s small bakery for some time. He then got a job taking care of the elderly for a salary of 180,000 colones (about 285 dollars or 10,000 córdobas at the approximate exchange rate at the time), much less than the minimum wage in Costa Rica.

He currently works 60 hours a week in the administrative area of a surveillance company where he is paid 320,000 colones (about US$630 or 23,000 cordobas), which is still less than the current minimum wage.

Although his salary doesn't stretch as far in Costa Rica as it would in Nicaragua, Karime is resolute in his decision not to return to his homeland. He is reminded of that from time to time by threatening voices, “from someone who tells me that they are going to kill me and that they already know where I live.”

Bradford studied Electronic Engineering and, when he discovered a taste for teaching, he realized he could make a living doing something he loved: training the next generation of engineers. However, he had to stop working when it was discovered that he had supported his students who participated in the protests that exploded in April 2018.

From his time as a teacher, he recalls how the students of UNEN [the pro-government National Union of Students of Nicaragua] were closing in on students who opposed the government. “They presided over each classroom, I had to exercise my work with great caution,” he says, detailing how several teachers had drawn up a list of UNEN students who should pass all subjects, including classes they did not attend.

After 2018, the university began to create groups of teachers who received T-shirts with messages alluding to the Government. They were pressured to participate in Saturday marches or instructed to report students who showed their nonconformity to the university hierarchy. Meanwhile, UNEN students spied on other students and teachers who expressed their opinions against the government.

Bradford’s departure from the country occurred unexpectedly. He recalls that he was already aware of the announcement stating that any teacher, administrator, or anyone working at a university, had to inform in advance if they wanted to leave the country.

While visiting Costa Rica, a friend from the faculty told him that “they were just waiting for me to return to Nicaragua, to do to me what they did to all the opponents, which at that time was to take them to El Chipote,” an infamous prison in the Nicaraguan capital. Bradford immediately decided to go into exile in the neighboring country.

Although he sought employment in the field he had studied he had to accept a position at a Spanish-language call center, after finding out that the Costa Rican state did not recognize his university degrees. To have them validated, he had to complete a complicated series of requirements, which included “having a driver's license of all categories.”

"You have to have certain certifications. Your degree must be validated by CONARE [the National Council of Rectors], which puts up a lot of obstacles. You practically have to start your degree again, because when you evaluate the curriculum in Nicaragua versus Costa Rica, many subjects have different names, so you have to retake them, meaning you have to repeat almost half of the curriculum,” explains Bradford.

He reports that he has received offers through an employment agency but always works jobs for which he is overqualified because here “our studies are not valid. They have no value, nor is our professional training recognized," he says tearfully.

Bradford is excited because, after sending his curriculum unsuccessfully to several centers and universities, he has just presented a summary of all his work experience and my degrees to the manager of a technical institute who offered him support to “make my technical degree valid, but not my engineering degree.” He can only validate his engineering degree when the agreement signed by CONARE with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) comes into force.

For now, he hopes to be able to teach again, and stop selling his skills as a thesis writer to a student at the University of Costa Rica; not to have to iron other people's clothes again, nor to take care of the small grocery store owned by the lady who generously offered him and his brother shelter in exchange for helping her sell sodas and snacks.

When Ignacio graduated as an Industrial Engineer in 2010, it was always clear to him that he was not looking for a prestigious company to employ him to take charge of its machines or systems. He went to a remote region in the north of the country, where there was no electricity for lighting, let alone to activate an engine to extract water.

“The last light pole was 60 kilometers away, so I designed a photovoltaic pumping system to bring them water. I took my system to an international competition. The project won, and the next year it was implemented. I was always attracted to social issues. I didn't pay a single córdoba to study at a university, which is why I wanted to give back. For me, it is more important to use my knowledge to help people than to go to a big-name company, like most of my peers,” he said.

After working for lumber companies in the industrial sector, and being hired by a German machinery company that sent him to Guatemala to train in pneumatic systems design, Ignacio studied “some English, as well as organizational structure, and then, in a self-taught way, I began to train with management software, which is a tool to avoid having to work in an archaic way.”

That allowed him to remain widely known in the industrial engineers' guild, which in the long run would have many positive consequences, when he was called to teach at the university level. But there was also a negative consequence, once the regime took notice of him.

The news that the prestigious Central American University (UCA) offered him a specialized class called Plant Design, (also known as Industrial Facilities Planning and Design), filled him with pride. This was magnified by an international evaluation that rated him “five out of five, and gave me glowing recommendations. Afterward, the UCA asked me to design the Production Planning and Control 1 and 2 classes but adjusted to the Nicaraguan labor market. Then they offered me a position teaching those clases, along with the Industrial Maintenance Management class,” he says

Ignacio shares that when the Ortega regime confiscated the UCA and tried to replace it with a new University called 'Casimiro Sotelo', (named after the young man who fought against the Somoza dictatorship, from the classrooms of the same campus), he received an unusual ‘non-voluntary offer of acceptance,’ to teach at the new university and to recruit other teachers to teach there.

"They contacted me because I know several teachers: some who are outside the country, some who are in jail, and others who have stayed in the country by remaining silent. They told me: 'we have this spot for you,' and I asked directly: 'Can I say no? “I don't recommend it,” they told me. So I said yes, but asked them to give me a chance to complete several jobs I had been assigned and paid for, and they allowed me to show up the first week of January with my resume, supporting papers, passport, and ID."

Those who did show up with all that documentation had their passports taken away. By the first week of January, Ignacio was no longer in Nicaragua: he crossed the border with Costa Rica on foot, accompanied by his wife and daughter “harassed by the Army and the Nicaraguan Police,” but feeling blessed by the support received from two organizations that helped them leave.

Although he was able to find a job as a technician, Ignacio is not content with simply earning a salary to pay his bills, so he is looking for a way to “create a small business,” as well as designing an administration course for small family businesses, which he is presenting to different organizations in the hope that they will help him make it a reality.

This article was published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff. To get the most relevant news from our English coverage delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to The Dispatch.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Durante más de veinte años se ha desempeñado en CONFIDENCIAL como periodista de Economía. Antes trabajó en el semanario La Crónica, el diario La Prensa y El Nuevo Diario. Además, ha publicado en el Diario de Hoy, de El Salvador. Ha ganado en dos ocasiones el Premio a la Excelencia en Periodismo Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, en Nicaragua.

PUBLICIDAD 3D