15 de agosto 2023

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Migrants are left trapped in a city haunted by the dangers they thought they had left behind. They can't move forward with their dream or go back

Ilustración: Confidencial

“It's been very hard. I try to be patient,” says Samuel, who arrived in Ciudad Juarez with only the clothes on his back. “I don't feel safe here, either,” confesses Luis, after recounting how Mexican officials took all the money he was carrying for the journey. Jorge, who has been waiting for more than six months to cross into the United States with his wife and two young daughters, says in despair, “I wish I could just fly and get to the other side.” All three are Nicaraguan migrants stranded in Ciudad Juarez, in northern Mexico. They got stuck just one step away from the “American dream.”

None of these men planned to stay in this border town for so long. They left Nicaragua fleeing the socio-political and economic crisis. They wanted to leave hunger and repression behind, but on the way they encountered dangers they hadn't counted on: robberies, kidnappings, extortion.

Some have had to sleep on the streets or in shelters. Others, who have had more “luck,” have stayed at an acquaintance's house, or rented a bed or mattress in an overcrowded hostel. They buy food with what little money they can come up with, or depend on soup kitchens. Those who are “better off” have found precarious jobs.

On January 5, 2023, the United States announced a program to reduce irregular migration from Nicaragua, Cuba, and Haiti, as it had done in October 2022 with Venezuelan migrants.

Under the name of humanitarian parole, the administration announced that it would accept 30,000 migrants per month from these four countries. But in a parallel move, the U.S. ordered the closure of its border and the “immediate” expulsion of migrants attempting to cross into U.S. territory illegally.

“We were on our way, my wife, my two daughters, and I, along with two other people, when they closed the border [in January]. The others turned back, but we decided to move forward because we couldn't go back to Nicaragua,” says Jorge.

“I didn't make it through,” laments Luis, who at the end of December was “stuck” in a shelter in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

Samuel only found out about the new immigration regulations when he arrived in Ciudad Juarez at the beginning of June. “I came here and got the news,” he says, disappointed. He says that he ran out of money “way back” and had to travel “hopping trains, without food or water, enduring the cold.”

Luis, Jorge, and Samuel left Nicaragua because they did not feel safe. “The [local Sandinista] political leader on the block would come to my house to demand that I participate in demonstrations in support of the government, but I refused. That's why I left, for fear of reprisals,” says Luis, 44.

Jorge, on the other hand, was an officer in the Special Police Operations Department, the National Police's anti-riot corps. He resigned because he disagrees with the repression ordered by the Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo regime. “What was happening is not right,” he said.

Samuel, 24, participated in the civic anti-government protests that erupted in April 2018. The protests were violently repressed by the regime, leaving 355 killed, more than 2,000 injured, and hundreds of thousands exiled due to political persecution. Samuel was one of many who first left for a couple of years to Costa Rica. “I returned [to Nicaragua] thinking that everything was fine, but it was always the same harassment,” he says. He left the country again, this time for the United States, and arrived in this border city, which for now is as close as he can get to his destination.

At the beginning of June 2023, a CONFIDENCIAL team traveled to Ciudad Juarez to document the conditions of stranded migrants like Luis, Samuel, and Jorge, who hope to obtain asylum in the United States from Mexico.

Despite having left Nicaragua months ago, and being more than 2,500 miles away, the three men asked for their true identities to be withheld for fear of reprisals from the regime against their relatives who remain in the country.

All three are living under harsh conditions in Ciudad Juarez, but none are considering returning to Nicaragua. “If I don't make it across, I would look for another country, because I don't plan to return to Nicaragua,” says Samuel.

Luis left for the United States at the end of 2022. On December 23 he arrived in San Pedro de Tapanatepec, in southern Mexico, where he planned to apply using the Multiple Migration Form to continue to the northern border. During the application process, he was informed of the border closure and had to stay in a shelter in Oaxaca.

Four months later, Luis was encouraged to “go north” with a group of Venezuelans. He thought that in Ciudad Juarez his situation would improve. But when he arrived in Chihuahua –225 miles from what he thought would be his last stop– he was robbed of all the money he had. “I had brought $1,500 for the trip, but some officers took it from me. They told me I had to give them money if I wanted to continue,” he says indignantly.

Now Luis spends his days in another shelter in Ciudad Juarez. He sleeps in the facilities set up by a Christian church and eats in the community dining room that offers lunch daily to some 250 migrants.

For his part, Samuel visits the same soup kitchen every day. He goes there to eat his only meal of the day, rest and recharge his cell phone. But he does not sleep in this or any other shelter because he has not found a space.

Iveth Marín, from the Refugee Service of Ciudad Juárez, explains that “the shelters do not have the capacity to receive all the migrants.”

Distressed, Samuel says: “I was paying rent with some money that was sent to me, but it was only enough for three days. I have been sleeping on the street, under one of the bridges that go to El Paso [Texas].”

“The hardest thing was not knowing where to turn”

Across from the community dining room of the Cathedral of Our Lady of Guadalupe, in the Plaza de Armas in Ciudad Juarez, dozens of migrants camp out during the day. They arrive there in search of a job or informal work to cover their daily expenses while they wait to cross into U.S. soil.

“We are waiting to get small jobs to be able to buy a soda, or to get money to keep going,” says Carlos Hernandez, a Honduran migrant.

“Here you need at least 200 Mexican pesos [about $12] a day to survive. It depends on how many meals a day you eat,” Carlos adds.

Xiomara Obando, 48, is sitting near Carlos. She is originally from Masaya, Nicaragua. She arrived in Juárez in June “without any money.”

“The hardest part was not knowing where to turn, because I didn't know about any of the shelters,” she says.

Another migrant that Xiomara met during her first days in the city gave her a place to stay in a small private house, and she subsists on the small amount she earns as a domestic worker and nanny: 300 Mexican pesos a week, about $18.

Two of her older children support her from time to time, sending her remittances from Costa Rica, where she had emigrated with them in 2018, as a result of the political crisis that broke out in Nicaragua.

Not having documents prevents Xiomara from getting a job with better conditions. “They ask for a lot of papers to be able to work, starting with my birth certificate. But to get it, I would have to go back to Nicaragua to look for it,” she says, disappointed. As others have expressed, Xiomara says going back is not an option.

In the Plaza de Armas, some migrants have decided to beg for money. Or they clean car windows on the busiest streets of this city, where the average temperature in June is around 95 degrees Fahrenheit.

What they will eat or where they will sleep are just two of the migrants' concerns while they wait in Ciudad Juarez, once dubbed "the murder capital of the world" because of its high homicide rate.

According to data from the Chihuahua State Attorney General's Office, between January 1 and June 15, 2023, 1,005 people were victims of homicide in the state of Chihuahua. 546 of them were in the northern zone, where Ciudad Juarez is located. That is an average of one victim every four hours.

A report by InSight Crime, published in June, indicated that “the growing trafficking of migrants and synthetic drugs could be the explanation for the recent increase in homicides in Ciudad Juarez, which has failed to break out of the cycle of violence that began after the start of Mexico's drug war” in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

The report said that some officials in the area believe migrants are a new cause of “violent turf wars” that were previously more related to drug trafficking. Criminal groups on the border have become increasingly involved in the trafficking business,” says the report.

Migrants are also exposed to theft and scams on a daily basis.

“I am afraid. I don't want to stay here by myself,” Luis says anxiously. Then, in a very low voice, he tells of another scam he recently suffered. “My friend who is going to receive me in the United States sent me some money to that man's [he points to the man] account, but when he was going to give me the money he said that his account was blocked.”

This type of scam against migrants is very common in Ciudad Juarez.

Xiomara was robbed of money that her children had collected for her. “My children sent me $30 to a man's account, but he kept it. His account was supposedly blocked by the bank,” she says.

Iveth Marín, of the Refugee Service, comments that migrants “unfortunately are easy prey” for both common and organized crime. She says they are exposed to scams, theft of their belongings and documentation, “express” kidnappings, torture, and labor exploitation.

Three blocks from the Plaza de Armas, Jorge lives and works in a hostel that rents rooms and beds by the night.

“My family and I stayed here when we came [in January], and then I stayed working here to pay the rent and cover other expenses,” he says.

Jorge is not formally registered as an employee at the hostel, but he has to work long 12-hour days and only has one day off a week. “Here, I have to do everything: charge customers, clean, be at the front desk,” he says. But he has no other choice.

Overcrowded with no room for complaints

More than 200 migrants are housed in a three-story hostel. The prices per room cost at least 400 Mexican pesos (about $24) per night. Most of the migrants can't afford the cost of a room on their own, so they usually sleep in groups.

Next to the reception area, there is a space with 15 beds. Another group of migrants sleeps there. They pay 200 pesos per bed (about $12) per night. “If you can only pay 100 pesos, they make you sleep with someone else in a bed, even if you don't know them, to get the 200 pesos,” complains one of the migrants.

While the CONFIDENCIAL team was talking with the “guests,” one of the hostel administrators said aloud: “Here they [the migrants] should give us some of the food they cook. They should be grateful because we're receiving them.”

In some of the corridors of the hostel, mattresses have been placed on the floor to “receive” more migrants when the rooms are full.

Marín warns that the local authorities ignore the complaints filed by the migrants, which only aggravates their situation of vulnerability and lack of protection.

On March 27, 40 migrants died in a fire at a migrant detention center. The tragedy caused indignation and questioning of Mexican authorities for their treatment of the migrant community.

Hundreds of migrants protested and refused to stay in municipal shelters, fearing a repeat of the event.

“After the fire, migrants began to distrust the authorities even more,” adds Marín.

Social and religious organizations have denounced that municipal and state institutions in Ciudad Juarez don't show a “real interest in protecting and providing attention” to the migrant population.

Santiago González Reyes, director of Human Rights in Ciudad Juárez, acknowledges that there is no coordinated plan of attention and protection for migrants among municipal, state, and federal authorities. “There are not enough resources to attend to all of them,” he says.

Before midnight on May 11, hundreds of migrants stranded in Ciudad Juarez turned themselves in to U.S. authorities in a last-ditch attempt to reach the longed-for "American dream" before the end of Title 42 and the resurgence of Title 8. The rule allows U.S. immigration authorities to remove anyone who arrives irregularly and prohibits them from re-entering the U.S. for at least five years.

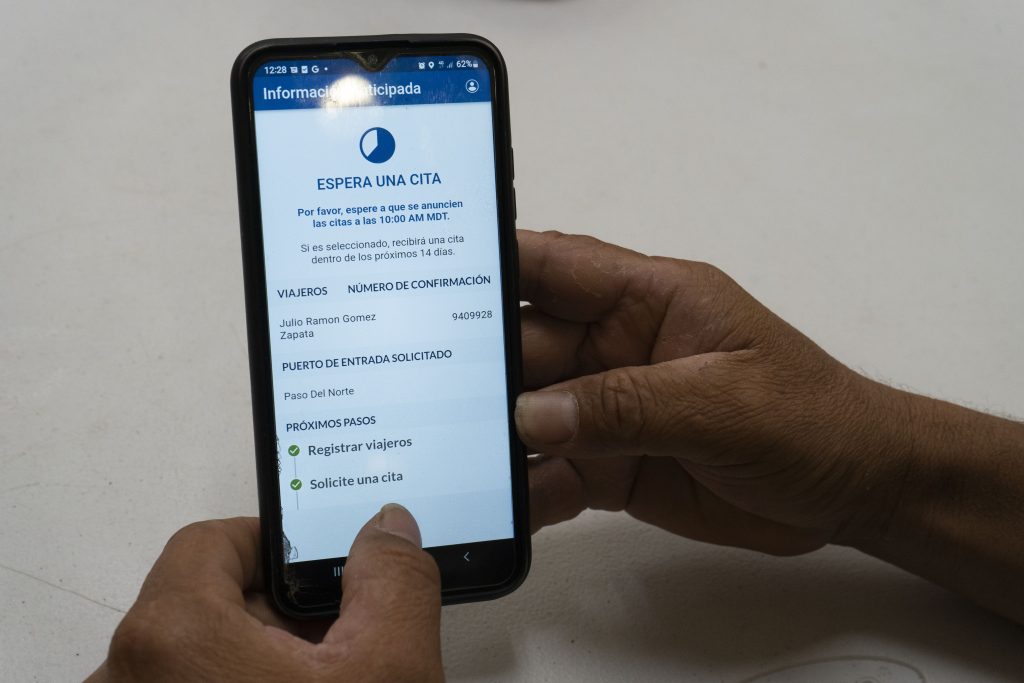

The U.S. says that it will only accept people at the border who have been denied protection in another country through which they have transited, and those who schedule an appointment in advance through the CBP One mobile app.

After the appointment, the asylum case is evaluated at one of the U.S. ports of entry. The mobile application was presented by the Joe Biden Administration as a way to "facilitate the process", but it has become a "headache" and the "last impediment" of a long journey for hundreds of migrants who are stranded on the Mexican side.

"I've been waiting for two months for an appointment, but I can't get one," laments Xiomara. Luis and Samuel are in the same situation. "I always go to the application and to my email, to see if I have already received the confirmation, but nothing," says Luis. "This is like a lottery because some get it quickly and others have to wait for a while," complains Samuel.

Testimonies of migrants complaining about the deficiency of the system are repeated along the border crossing between Ciudad Juarez and El Paso, Texas.

Not being able to complete the login, the constant blocking of the application, and problems taking the requested photograph are some of the most frequently reported failures of CBP One.

Attorney Melissa Hernandez, of the State Population Council (Coespo) in Ciudad Juarez, acknowledges that in recent months they have seen "many changes for the better" in the application. "Now," she adds, "it is available in English and Spanish, migrants can present any type of identity document, not just a passport or birth certificate. More space is also given to families requesting the appointment when before priority was given to those traveling alone," he sums up.

However, the main problem continues to be the saturation of the system, as there are only 1250 appointments available per day, for a total of eight ports of entry along the border, with thousands trying to get a slot.

Hernandez says there is no exact information on how many people are seen each day at the Paso del Norte International Bridge. According to his observations, around 150 appointments are attended daily. Jorge regrets that he does not even have how to get that lottery ticket, in the absence of an ID to get an appointment. "I don't have a passport, and my identity card is in Nicaragua," he expresses helplessly.

Faced with the desperation of not being able to get an appointment, some migrants opt to cross irregularly to U.S. soil. However, they risk being turned back and being banned for the next five years, as well as facing criminal prosecution if they try more than once.

According to a statement from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), in just 20 days - between May 12 and June 2, 2023 - they repatriated more than 38,400 migrants to more than 80 countries, including families. Among them, 1400 were migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela who were returned to Mexico.

Mexican civil society organizations have denounced that repatriations and expulsions of migrants are carried out with little transparency, and without making clear the care schemes under which they are being processed.

Enrique Valenzuela, the general coordinator of the State Population Council (Coespo), limits himself to expressing that Mexico's "federal authority" has been discreet with this information.

On July 28, the U.S. government announced that it will accept asylum requests from nationals from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela who are already in Mexico waiting to cross into its territory, in an attempt to decongest the border on the Mexican side. However, no further details have been provided.

Nicaraguan migrants who are not considering the option of returning to Nicaragua, continue to be attentive to any possibility that will open the doors they have been waiting for so long. Luis, who left in December with a clear plan and arrived in Mexico with some resources to cover his trip before being the victim of robbery and fraud and having to sleep in a shelter and eat in a community dining hall, clings to his dream: "If they reject me," he says, "I don't know what I'm going to do. I haven't thought of another option.

This report is part of a special series by news teams from Confidencial (Nicaragua), Plaza Pública(Guatemala), and Revista Factum (El Salvador), who traveled to Ciudad Juárez, on Mexico's northern border, and Tapachula, on the southern border, in search of Migrants Stranded in Mexico.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by our staff.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista y productora audiovisual nicaragüense. Licenciada en Ciencias Políticas. Cofundadora de varias organizaciones de sociedad civil vinculadas a la lucha por los derechos de la comunidad estudiantil en Nicaragua. También se ha desempaño en proyectos de transformación digital para empresas y organizaciones.

PUBLICIDAD 3D