13 de agosto 2023

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

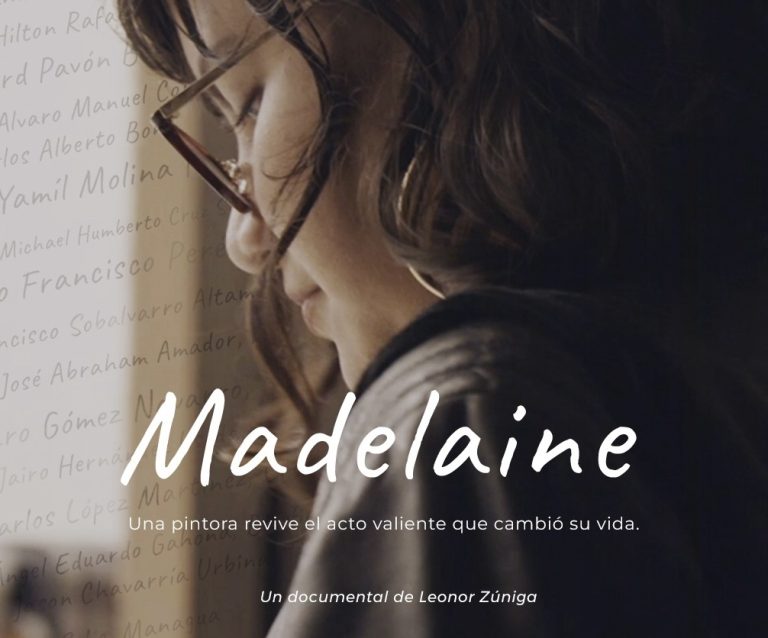

The film explores the story of the young woman who read the names of those killed by state repression in front of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo

Nicaraguan filmmaker Leonor Zuniga’s new documentary puts the existential dilemma of exile at the center.

Having experienced it first-hand, like tens of thousands of Nicaraguans who have been expelled by the regime’s political persecution in Nicaragua over the past five years, Zuniga looks in the mirror as she tells the story of a young university student and artist whose life changed forever after joining the student protests against the government of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo during the April Rebellion of 2018.

She is Madelaine Caracas, one of the voices that resounded throughout the country in the first televised attempt at national dialogue in May 2018, when President Ortega and Vice President Rosario Murillo showed up after the massive protests against them and the brutal repression that had already claimed dozens of lives. Caracas replied to Ortega, who asked for a list of the victims of state repression. One by one, she read the names of the dead in a historic moment that changed her life forever.

From exile in Costa Rica, after death threats and imprisonment, the young woman reflects in front of the lens about what happened, revealing her grief, fears, uncertainties, and hopes. Filmmaker Zuniga, director of the documentary, tells us in this interview the purpose of this short film, which she titled after its protagonist, Madelaine, and invites those who are in Costa Rica to attend the premiere this Saturday, August 12, at Sala Garbo in San Jose.

Your documentary follows Madelaine Caracas. She is one of several young people who became protagonists during the April Rebellion in Nicaragua in 2018 when they were part of the national dialogue which sought a way out of the crisis that erupted due to state repression. Why Madelaine? How did you decide to make a documentary about her?

This initiative is part of a series of documentaries being made by the production company Tres Felices Tigres, headed by Roberto Guillen, about artists in exile. That is a facet of Madeleine that people perhaps don’t know. She is a great painter, besides also being a performer.

Roberto asked me if I was interested in being the director of this project. I only knew Madeleine as a student leader, but I was very interested in making a documentary about her from a different perspective, more intimate. My quest is always to make documentaries that defy a little the external image that we project and, instead, look for the intimate level of these people.

Exile is a recurring theme in your work, and women are the main subject. We saw that in 2019 in the documentary Exiliada (Exiled), which narrates the story of Daniel Ortega’s stepdaughter, Zoilamerica Ortega Murillo, who denounced him for sexual abuse. Is it a coincidence or is there an intentionality in this choice?

There is an intentionality. In this case, I was invited to be the director, but I was asked precisely for my viewpoint and because the subject is of interest to me. I am very interested in the emotional side of injustice, and female characters are the ones I primarily identify with; above all, I am very interested in the duality women present: as outsiders, as leaders, as spokespersons for themselves or for a cause. And that image is generally powerful and relatively rigid because they must protect themselves from the violence in Nicaragua against women. But when you enter the private sphere, many things flourish, contradictions, a more vulnerable part of who we are, and I like that because it is precisely what I am interested in exploring.

Someone could make a documentary about what happened to students on a public level. That is fine, but for me, Madeleine (the documentary) deals with being young, being 20 years old in Nicaragua.

And there is the issue of today where exile marks tens of thousands of people that have left Nicaragua since 2018, including you.

Exactly. Yes. When I made Exiliada, I was not in exile, but I knew that making that documentary could put me in a vulnerable position, which could cause me to end up in exile.

In the case of Madeleine, it was like a kind of mirror in which I was exploring the central theme of who you are when you have lost everything, which was also a doubt I had. I lost my country; I could not see my family; I lost my company; I had to begin anew here (in Costa Rica). Many things that I thought were fundamental to my identity were lost, I had to restore them, and when that happens, you wonder who you are.

For me, Madelaine, through the documentary, is what is being asked the most, who is she? She is the girl everyone thinks they know, but this woman is also a painter, and she is in a sort of quicksand where her identity is being transformed.

There are already several documentaries on the outbreak of the April Rebellion in Nicaragua. Is that the purpose of this work? Is this a way of exploring that event through the personal experience of one of the young people?

In everything I’ve worked on recently —including the documentary Exiliada, I was also the cinematographer of Los Minusculos, and Patrullaje which has just come out— has to do with the current reality of Nicaragua, with injustice and questioning the development model.

You cannot discuss Nicaragua’s present without passing through the April Rebellion. It is a central focus in so many aspects of our lives that, whether you want it to be or not, it is there, and you must explore it. What I try to do, and also from our film production company (Juli Films), is to find places that are not so informative or that deal only with the public plane or of known figures, but the intimate shots or the peripherical places which are generally not spoken about.

How do you expect the documentary to be received by Nicaraguans inside and outside the country?

I don’t know what to expect, honestly. Sometimes I make documentaries that do not necessarily meet the expectations of what a documentary should be. For example, about Zoilamerica or Madelaine, because usually, I don’t emphasize explaining the context too much. I put more emphasis on understanding the emotional space they inhabit.

Some people identify with those spaces and others would like me to do another type of work that is more forceful about (for example) the role of Daniel Ortega, but it’s always interesting to see people’s reactions to this work that goes in another direction.

Tell us about the premiere of this short film in Costa Rica.

It will premiere in the Festival Shorts Costa Rica, exclusively reserved for short documentaries. It will be in the Competencia Centroamericana (Central American Competition) category and will be presented August 12th at Sala Garbo at 4:00 p.m. This is our premiere in Costa Rica because we have already shown it in two festivals in the United States: the San Diego Latino Film Festival and the Philadelphia Latino Film Festival. It was also presented in Mexico, in Queretaro, at the Doqumenta Festival.

Will it be available online, eventually?

Yes, it will be available online. I hope it does not go beyond the end of this year. And we will also make Exiliada available to the public, even if only for a limited time.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense desde 2007, con experiencia en prensa escrita, televisión y medios digitales. Tiene una especialización en producción audiovisual y una maestría en Medios de Comunicación, Estudios de Paz y Conflicto de la Universidad para la Paz de las Naciones Unidas. Fundadora y editora de Nicas Migrantes, proyecto por el cual ganó el Impact Award 2022 del Departamento de Estado de EE. UU. Ha realizado coberturas in situ en Los Ángeles (Estados Unidos), México, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua y Costa Rica. También ha colaborado con France 24, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, BBC World Service. Ha sido finalista y ganadora de varios premios nacionales e internacionales, entre ellos el Premio Latinoamericano de Periodismo de Investigación Javier Valdez, del Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS), 2022.

PUBLICIDAD 3D