11 de julio 2023

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

From exile, different natives of Nicaragua’s Carazo department speak about the protests, government attacks, and the July 8, 2018 massacre

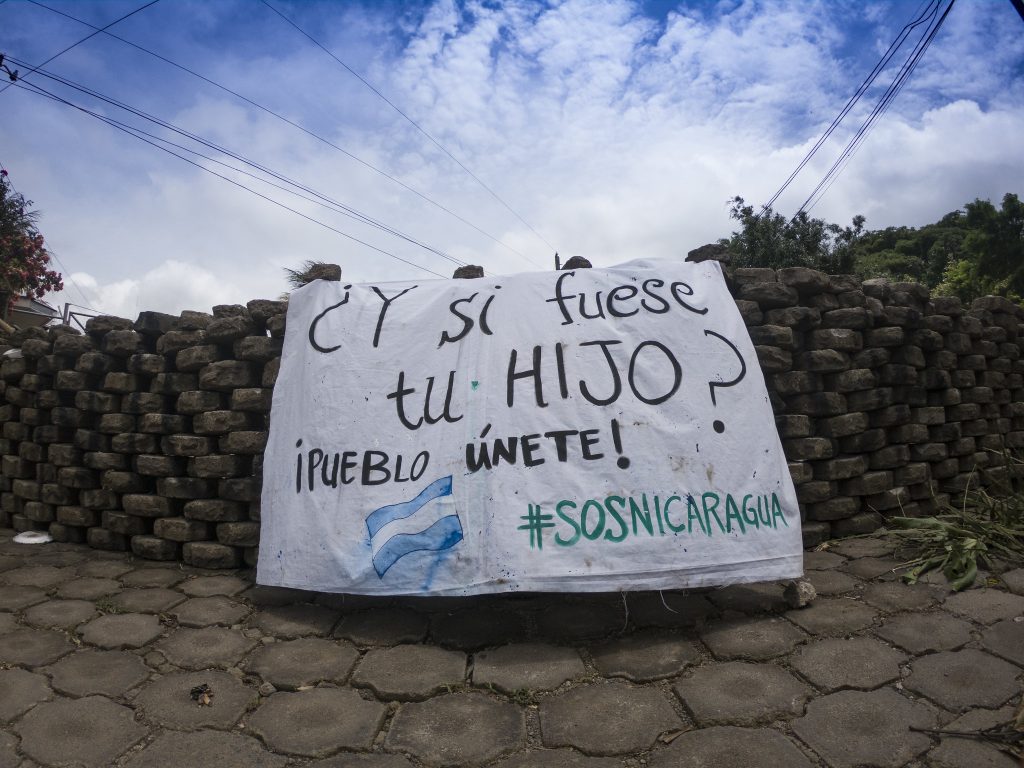

Autoconvocados en uno de los tranques de Carazo, 2018. Foto: gallotronic08.

"Pueblo únete [people unite]," Kevin Roman chorused while leading the first march that was held in Carazo on April 19, 2018. Along with him, dozens of self-organized protesters marched down the main streets of Jinotepe to express their discontent with the reforms Daniel Ortega had announced to Nicaragua’s Social Security system. They were also marching to demonstrate their indignation over the brutal treatment that elders protesting the unfavorable changes had received from the police and the Sandinista mobs in Managua and Leon the day before.

A violent panorama had been unleashed in Nicaragua that Wednesday afternoon of April 18. The police and the mobs had come in swinging against activists who accompanied the protest, and against the journalists covering the events. “When I saw the news clips of what was happening, I cried with indignation,” recalls La China, who took on that nickname in April and asks that her true identity be safeguarded.

La China participated in the Carazo protests from the time of that very first march, without imagining that these demonstrations, too, would be repressed in the same way. “On April 19, I went to the park, because I heard that the university students were gathering there. Some 30 of us began marching, and by the end there were over three blocks of people from Jinotepe marching through the town. However, they attacked us the same way they attacked the demonstrators in Managua,” she states.

“We were fed up with the corruption, the indoctrination, the embezzlement of funds and resources. Days before, university students had also protested against the burning in the Indio Maiz biological reserve,” recalls Moises Silva.

“My participation in the struggle wasn’t born in April; my discontent comes from before. I participated in the ‘Protest Wednesdays’ and supported the farmers’ protests against the canal project,” says Martha Valeria Ortega.

As in Jinotepe, the town of Diriamba also began to protest. Other municipalities in the department of Carazo would soon join in. That day – April 19, 2018 – saw protests, marches and caravans. “People poured out to show their opposition to the government. Most of the inhabitants of Carazo joined in spontaneously, regardless of their political or religious affiliation,” affirms David Conrado.

As the demonstrations became larger, the level of repression increased. The Sandinista mobs and some of the public employees from different institutions began to threaten the Carazo protesters with shovels and mortars. Later, the threats were taken up by the police and paramilitary, this time armed with guns.

On April 21, there were reports from Carazo of a number of protesters wounded by bullets and mortars, as well as fires that broke out in the Sandinista headquarters of Jinotepe y Diriamba.

“We were aware that the government was organized and prepared to dismantle any demonstration by any means possible. We were already seeing bullets used in the repression, and that was one of the reasons we felt the need to organize ourselves,” Moises explains. That’s how the self-organized protesters of Jinotepe, Diriama, Dolores and San Marcos formed the April 19 Movement, he continues. From that moment on, Moises took on the role of activist and territorial leader for the department. La China, Martha Valeria, Kevin and David also formed part of the movement.

“The intention was to coordinate the marches and provide security for the march route,” explains Xaviera Molina, another member. The movement was organized into various groups that carried out specific tasks. One of them was the communication and logistics group, in charge of directing and organizing the different activities that took place during the protests. There was also the medical group, responsible for providing first aid to the protesters in case of any eventuality, and the group for strength and confrontation, whose task it was to protect the marches.

“These groups were present at all times, even when Carazo attended the marches in Managua,” adds Xaviera.

After the massacre that occurred in Managua during the massive “Mothers’ Day” march on May 30th, a group of the independently organized protesters decided to block access to Jinotepe permanently, by barricading the road by the San Jose School, the main route of the Pan-American Highway. “The murders continued, and we didn’t see any intention on the part of the government to stop the repression. We decided to create a roadblock, because we thought it would affect the economy and thus lead the government to cede. However, it was also a form of protection,” Moises clarifies.

On Thursday, May 31, the San Jose barricade completely blocked passage along the highway, impeding the circulation of national and international freightliners and other trucks that used this route. As the days passed, the blockaded vehicles began to pile up.

Now the movement had another task: to provide humanitarian aid to the drivers who were stranded there. “We guaranteed them three meals a day; we coordinated with places where they could clean up and take care of their necessities; they were given medical attention; and we even looked for a way to get medicine for those who had chronic illnesses,” Moises assures.

The San Jose roadblock received the solidarity of the people of Carazo. Day after day, people came with clothing, food and medicine for those who were guarding the barricade or were marooned there. “Not only the parents of the protesters came to help, but also people from the entire town gave support,” Alva Patora Mojica, David’s mother, recounts.

Martha Valeria formed part of the group in charge of preparing the food that was given out daily. “Thank God, right up until the last day of the roadblock, we were able to serve food to the guys [at the barricades], and to the truck drivers,” she comments.

The barricade, which Daniel Ortega accused of slowing the economy and hindering citizens’ free movement, was backed by the townspeople themselves.

The trucks began sounding their horns in the very early hours of June 12, awakening the town and warning of a possible attack. Pick-up trucks full of riot police and paramilitary were heading towards the San Jose School with the aim of dismantling the barricade.

“It was dark and we didn’t know what street they might appear from, but we knew that they were close. The horns wouldn’t stop blaring. When I yelled at the guys not to be too quick to trigger the mortars, the first shots were heard,” Lenin Rojas recalls.

As the bullets came closer, the bells of Jinotepe’s Santiago Apostol Church also began to ring, alerting the townspeople, who immediately went out onto the street to protect the protesters. “As soon as I heard the ruckus, I left my house in pajamas. There were already a lot of mothers in the streets, and we approached the school in a procession, banging hard on some frying pans. At that moment, I had no fear of the paramilitary or the riot police threatening or shooting at me. I thought only about going to protect my daughter,” expresses La China’s mother.

That day, the united population came out onto the streets. The paramilitary and riot police retreated without accomplishing their objective. After that, the inhabitants of Jinotepe used wires, cement blocks, piles of chairs, sacks and any material they could find to blockade each neighborhood and block of the entire city of Jinotepe.

“It felt good, because there was an atmosphere of help, equality and love for your neighbors. Jinotepe had more than 100 barricades – from north to south, from east to west, and after that June 12 people spent over 26 days watching over their corners, in order to sound the alert or bang the pans in the event of another attack,” Moises explains. Similar situations occurred in the streets of Dolores and in Diriamba.

David remarks that at that moment, they felt like they’d won the fight. “The actions and protection of the people filled us with strength. We felt that victory was ours. But we weren’t counting on the fact that the government would go to the extremes of what happened on July 8,” he adds.

In the early morning of July 8, 2018, neither the truck horns, nor the frying pans of the protesters’ mothers could halt the over two thousand paramilitary that entered the Carazo cities fully armed to dismantle the department’s roadblocks. The Ortega-Murillo regime had christened their action “Operation Clean-up,” a massacre that left at least 12 people dead and over 30 tortured and imprisoned.

The paramilitary and the police contingents advanced silently, but with their strategies well laid out, determined to eliminate the roadblocks, along with anything else that got in their way. “I remember that at five in the morning, my oldest son called me. I leaped out of bed with a start, and asked him: ’What happened?’ He said ‘Mother, mother, they’re attacking us, they’re attacking… They’re coming in through all the streets that lead to Jinotepe – streets, bypaths, everywhere, it’s a full sweep,’” Alba Pastora recalls.

After nearly 12 hours under a hail of bullets, silence and uncertainty reigned in Diriamba, Dolores and Jinotepe. “Everyone just locked themselves in. That day, there was neither electricity or internet for a long time. I remained closed into the church with six other people, without any news of my family,” Martha Valeria relates.

The massacre that happened on that Sunday, July 8, left Carazo in mourning. “It was a bitter night. A lot of families were left devastated on that day. Mothers condemned to die without their children there; many wives left widowed; children were orphaned,” Kevin comments.

On the morning of July 9, a committee made up of Catholic Church representatives and human rights advocates traveled from Managua to Diriamba and Jinotepe to mediate in the attacks that had been perpetrated the previous day. When they arrived at the San Sebastian Basilica in Diriamba, they were assaulted by Ortega regime mobs and paramilitary. Independent journalists were also attacked, and some had their equipment stolen.

The protesters who had taken refuge in the Jinotepe parish couldn’t leave, for fear of being trapped by the paramilitary. “We stayed there in the Church, waiting for everything to calm down, without knowing that after the attack suffered by the priests in Diriamba, the mobs were moving on towards Jinotepe, to do the same thing,” states Martha Valeria Ortega.

At eleven in the morning, the paramilitary and the Sandinista mobs broke into the Santiago Apostol Church. “I asked the Vicar to hide us, because I knew that if they trapped us there, they’d kill us. So then, seven of us hid us behind a clothes rack where they hung the capes used to drape Santiago (the patron Saint of Jinotepe). Two of us were wounded, but we remained there in silence for over five hours,” Martha Valeria continues.

While the self-organized protesters stayed hidden, the paramilitary profaned and looted the church. They shot their guns inside the temple to inspire fear, they pulled out and broke the benches, threw boxes of medicine to the ground and later set fire to them, and they struck and threatened the Vicar, Father Edgar Eliseo Vargas and Father Jalder Hernandez.

“We thought we were going to die. We heard the yells and the curses from outside, where they were threatening to burn down the Church,” states Moises, who was among those hiding inside the Church. When night fell that day and the mobs stopped their watch on the church, they managed to get out.

After Operation Cleaning in Carazo, the department remained under a police siege. “There was a lot of harassment of the homes where people had protested. Their houses were tagged with graffiti bearing the notorious word Plomo [literally “lead,” both a Spanish acronym for the FSLN motto and a reference to bullets.] They stalked the victims’ families in the midst of their pain,” says Kevin.

David recalls how Jinotepe filled with patrol cars loaded with police and paramilitaries, looking for people who had participated in the marches and roadblocks. “They went to the houses in search of the protesters. If they found them, they arrested them; if not, they beat the relatives and caused damage,” he adds.

Many of the protesters managed to escape from Carazo along rural roads, while others resisted in safe houses for a while. However, the siege was so strong that in the end many finally opted to go into exile. All the people offering their testimonies in this piece have requested international protection in the United States, Costa Rica and Finland.

“The police siege continues today; military intelligence continues to track anyone who may possibly have returned, or who they suspect could be organizing others. They keep them under watch, take them to the police, take their fingerprints and threaten them. In that way they’re neutralizing the activists who have remained in Nicaragua,” comments Moises.

Between July 8, 2018 and the present, some 60 people from the department have been detained according to Lenin, coordinator of the Blue and White Movement of Carazo. The majority have been released and have fled into exile.

Beginning in 2019, several days before July 8, the regime has mobilized its sympathizers to participate in caravans they call “Here’s Free Carazo”. Despite this intimidation, the people of Carazo continue resisting. The families hold prayer sessions in the Jinotepe parish church of San Antonio, and light white candles in memory of the fallen, notes Martha Valeria. From exile, these dates are commemorated with demonstrations, vigils, or Masses.

“Since we arrived in Costa Rica, those of us from Carazo have always gathered on July 8 to recall our fallen and our brothers and sisters who have been victims of the repression,” states Lenin.

This year won’t be any exception. The Carazo Blue and White Movement in Costa Rica held a vigil at Democracy Plaza in San Jose, Costa Rica.

From Finland, Kevin planned to meet with other exiles from Carazo to offer homage to those killed. “We want it known that Nicaragua is living under a dictatorship, and we also want it known that on July 8, 2018 a massacre took place in the department of Carazo,” he indicates.

“At five years since the massacre, fear persists – inside as well as outside Carazo. The cruelty with which the regime carried out their “Operation Clean-Up” has marked the lives of those of us who lived through it. Time will continue passing, but Carazo won’t forget,” Alba Pastora concluded.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense exiliada en Costa Rica. Se ha especializado en la cobertura de temas de migración, género y salud sexual y reproductiva. También ha trabajado en Marketing y Ventas y ha sido Ejecutiva de Cuentas.

PUBLICIDAD 3D