22 de marzo 2023

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Relative of ex-political prisoner: "We will keep reliving the anguish. Not until all the families are reunited will we be able to get back to living.”

More than a year and a half of anguish for my family. For others, two years, four, six or even more. Those were terrible days. Days of fear and uncertainty. At first we knew nothing: not where they were, nor how they were, nor what they needed. The jail didn’t accept anything from us. Then later, did they even get what we brought them?

We, the family members –full of pain, fear, uncertainty, doubts-- went every day to El Chipote to ask for news, to try to get some food and drinks to them. Many times we left crying, feeling assaulted, fearful for them and for ourselves. Little by little we discovered what they would accept and what they wouldn’t. We would try new things and when they were accepted, we shared those things with the other families so they could take them, too. Part of the torture for us was the lack of routines and norms, that everything was at their discretion. One day they would accept something, the next day they wouldn’t. They would tell us yes, but when we arrived with enthusiasm to deliver it, they would say no. Perhaps it was all to unnerve us and deepen our suffering, to make sure we knew that we were totally in their hands.

We suffered when at the beginning we weren’t allowed to leave more than water. Then we were allowed to leave protein drinks or yogurt. It wasn’t until much later –September of last year—that we could start leaving cookies and nuts and seeds. We suffered because we weren’t allowed to give them a blanket, a sheet, a sleeping mat. They spent nine, ten, eleven months or even longer, having to sleep without having anything to cover themselves with. We were finally allowed to get them mattresses in December 2022. That was two months before their departure.

In the prisons of the penitentiary system, visits would also be cancelled or packages from the families refused at the officials’ discretion. Each time it was an odyssey to get permission.

But I don't want to talk about all these hardships. Enough has already been said about them. The family members’ statements, the campaigns by human rights organizations, Sé Humano, and other groups committed to freedom, and the statements by the released prisoners themselves have documented all this in their own voices.

Today I want to talk about the love stories that were woven in the midst of those horrors, without mentioning names so as not to put anyone at risk.

I want to talk about the wife who went every single day at 6 a.m. to drop off water and nutritional drinks even though she could have gone only every other day, because going every day allowed her to feel close to her husband for a little while.

Or the wife who went three times a day with the hope that the drinks she brought would be given to her husband ice cold.

I want to talk about the partners, spouses, sons, daughters, mothers and fathers who traveled nine hours, or more, every week to drop off nutritional beverages.

Of the families who went without eating so they could pay for and bring the medicines their loved one needed.

I want to talk about the families who subjected themselves to the strict isolation measures so that their loved one could serve their sentence at home and not in the cells of El Chipote.

Of the sisters who would put their niece’s hair conditioner in their own hair, so that their imprisoned sister or brother could smell it and remember the daughter they couldn’t see.

I want to talk about the families who didn’t tell their loved one any bad news, but instead lived with those things in silence, because they felt their loved one had enough to deal with with what they were experiencing inside.

Of those of us who had to swallow our fear in order to publicly denounce hunger strikes, serious health conditions, prolonged isolation, or alleged aggressions so that the world would know what was happening and some action would be taken, and doing so at the risk of something happening to us.

I want to talk about the love of the family members who had to leave Nicaragua. Who had to live through all this from afar. Who were always present, even if they did not have the consolation of bringing their loved one a bottle of water, of going to visit them and hugging them in the most difficult moments, of feeling how their bodies were shrinking due to the lack of food. Of the love they expressed daily in their interviews, in their work and all their efforts to achieve freedom for all the prisoners. So much daily love in spite of living with the anguish of not being close and at the same time facing the grief that results from migrating or living in exile.

Of families who went into debt in order to bring a box of provisions (the jail only accepted industrially packaged foods) to mitigate the hunger of their loved one, even though they knew that they did not always receive everything they brought.

Of the joy of the two-hour visit. Of keeping an eye on the phone because we never knew when they would call us to tell us a visit was scheduled. Of planning our lives around calls that came at unexpected times. Of scouring supermarkets and sales to see what new protein-rich products we could bring them, and sharing the information with the other families.

Of the solidarity among families. Of sharing what we had. Of accompanying those who in different moments were suffering even more than usual. Of supporting each other with advice, information and resources.

Of the incredible miracle we felt when we were informed of the four-hour visits, with children included and with several family members, and when we discovered (testing the waters, because as usual they did not inform us) that we could hand what we had brought directly to our loved ones and that we could even bring them homemade food. Of the video calls, the reading of letters, looking at photos.

The love that was behind the decision to not put out a family members statement in December 2022 so as not to jeopardize those visits that were so important for both the political prisoners and for us, their families.

I want to talk about the children whose rights were violated at such tender ages. And when they were able to see their mothers and fathers after more than a year of total absence, they told them about their lives, filled them with joy and gave them comfort and love, a string of kisses and hugs. They showed them the gaps where their teeth had fallen out, their school report cards, and the drawings they had made for them. And in the terrible moments when they had to say goodbye, they would tell them "This is going to pass, mommy, today we got to see each other", "When you come back we will never be separated again", "I'm fine, dad, don't worry about me". Although at the exit they sobbed, and their crying would last days and even weeks. They should never have had to carry that weight, never have to live through that pain.

It was hard, it was terrible. We still live with a level of anguish that has not left our bodies. It will leave a permanent scar. We still talk in whispers, we look over our shoulders, we wake up startled in the early morning thinking that maybe today is the day it’s our turn to go to El Chipote to take the nutritional drinks and maybe we missed the time slot.

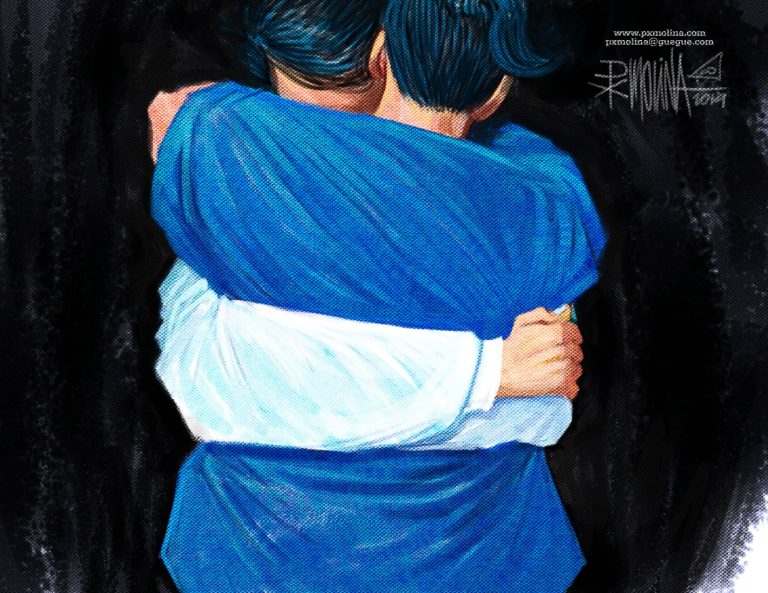

It still seems like a dream that they are free. And until we can see them and give them a hug without anyone limiting our time, we will continue to relive the trauma, the fear, the anguish. Not until all the families are reunited will we be able to get back to living.

There are still more than 38 political prisoners in Nicaragua and 38 families living that same horror and holding on to that same love. We yearn for their release, that it will soon become a reality.

This experience taught us how much we love each other and how love both takes on and overcomes all the fears and risks, and finds the cracks to show the other person that they are not alone, that we are with them, that they can always count on us. It is this love, which now blooms in full sunlight, that gives us strength in this new stage, even if it has to be in another country, even if, because of all the existing limitations, we are still uncertain whether we’ll able to be together as a family.

Even with all this, it is now up to all of us --the banished exprisoners and us, their families -- to allow ourselves to flourish, to reinvent ourselves,and to relearn how to live, free from those terrible four walls that separated us for so long.

Now it is time to recover time, heal the wounds --especially those of the soul-- and with the love that accompanied us this whole time, reaffirm our commitment to make sure that in Nicaragua it will never again be possible for people full of hatred to do so much harm to the nation.

The author of this testimony is a relative of a former political prisoner.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996. Inició como un semanario impreso y hoy es un medio de referencia regional con información, análisis, entrevistas, perfiles, reportajes e investigaciones sobre Nicaragua, informando desde el exilio por la persecución política de la dictadura de Daniel Ortega y Rosario Murillo.

PUBLICIDAD 3D