1 de noviembre 2022

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

The municipal “elections” are designed to certify the FSLN’s control over the population and the territories.

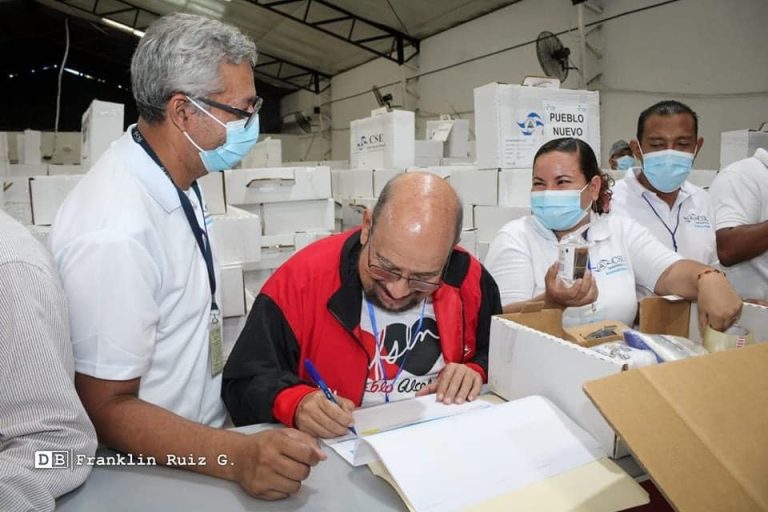

The legal representative of the FSLN, Edwin Castro, signs the approval for the transfer of the electoral material. Photo: Barricada

Five years ago I wrote an article entitled 2017 Municipal Elections, what the coming municipal model hides, for ENVIO magazine. In that article I highlighted two threats to municipal governments: the reduction of their role to mere implementers of the “Master Plan of Love for Nicaragua—Local Governments 2018-2022, Christian, Socialist and in Solidarity;” and the submission to FSLN political bosses.

The perspectives foresaw a worsening of the situation of the municipalities, which by that time were already tied up in the three aspects of their autonomy: the political one by the irrelevance of local elections and the dominance of political commissars; the administrative one by the takeover of their ability to decide their development plans; and the financial one by the invalidation of the laws that guaranteed revenues coming from the national budget.

However, although forecasts already warned of further deterioration, the social outbreak of 2018 made everything that could go wrong worse. From then on the local governments lost importance even more as the state shifted from a recentralizing state to a Police State. In this drift, the municipalities became the last link in the repressive apparatus, first as a source to recruit paramilitaries and later as the domain of the local police commanders.

This bankruptcy of the municipality —that is, its autonomy— has been confirmed by the study Here you obey, analysis of local power, carried out by Urnas Abiertas based on the perceptions of the population of 143 of Nicaragua’s 153 municipalities. The research identified 12 patterns or forms of exercising power at the local level. Among the actors associated with these patterns, political bosses, police chiefs and mayors stand out.

These patterns hide the fact that the policy of repression has been installed as the backbone of the state, a typical characteristic of Police States that confronted with evidence of popular rejection, opt to organize the public apparatus around surveillance and control mechanisms. The dictatorship renounced public policies and programs of universal coverage that could reward them some type of consensus support, such as those put in practice in the first years after its return to power (2007). Instead of that, it has opted for the brutality and bullets, persecution, and prison.

In this logic, the local governments are indispensable operative pieces for the control of the population and the territory. It is well-known that in municipalities “everybody knows each other,” by families, by occupation, by nicknames and, of course, by political affiliation. In each block, in each neighborhood or community it is known who the opponents are, who has a relative in prison or in exile, where suspicious meetings are held and even what is discussed in them. What is essential is no longer the communal problems but the security of the regime and hence of the commander and the “compañera.”

Even for the actions of the thought police, the dictatorship needs the municipalities to identify those who exercising their right to expression, give opinions contrary to the regime in such a non-territorial environment as the social networks. In this case, local governments use the administrative tools at their disposal to punish citizens they consider enemies with tax surcharges, fines, exclusion from municipal services and refusal of ordinary procedures, among others.

The patterns identified by the Urnas Abiertas study also hide the powers that be. The same ones that run the territory in societies trapped by organized crime, by very powerful economic groups or by local strongmen. In the current case, these are the political secretariats and police chiefs. Neither of them has been elected by popular vote nor are they subjected to municipal authorities. Some respond to the FSLN’s top-down structures and others to the hierarchical command of the departmental or national police leadership. They are powers to the extent that, acting outside the range of their legally declared activities and objectives, they exert influence and domination with the objective of subduing elected authorities, in open violation of municipal laws.

In the case of Nicaragua, these are people backed by the power of fear, by the prerogative of striking fear, of imprisoning people, of torturing and killing with absolute impunity before the cruelest helplessness of the citizens.

The fact that the population perceives them as agents of persecution with partisan purposes and not as public servants, above the legitimate authorities, is a regression to the time of Somoza, when the municipalities played roles of control and political information, including the heinous local judges.

Five years ago, the abyss that the City Halls faced was that they would end up reduced to administrative functions, to service tasks such as the maintenance and cleaning of the streets and the management of the markets. All under the guidance of FSLN operatives in charge of enforcing orders emanating from the central power in Managua. Then, after the 2017 local elections, they would become the last echelon of the repressive apparatus of a dictatorial regime that decided to take off its mask.

Through this repressive monstrosity, the Ortega regime wants Nicaraguans go to vote on November 6. Instead of electing a government closest to the people, the one they know and responds to their demands, it wants the repressed to give their consent to introduce the torturers inside their homes. Such shamelessness can only be conceived in the heads of those who knowing themselves rejected by the majority population only have the brutality and surveillance of a Police State to remain in power.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Politólogo y sociólogo nicaragüense, viviendo en España. Es municipalista e investigador en temas relacionados con participación ciudadana y sociedad civil.

PUBLICIDAD 3D