18 de febrero 2022

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Interviews taken out of context, Twitter posts and police “witnesses” who contradict each other comprise the “proof of guilt” of the political prisoner

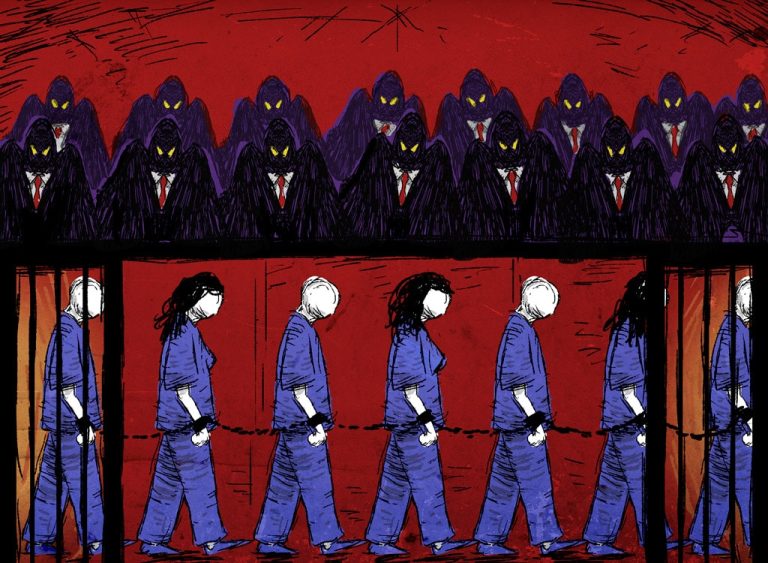

On February 1st, Yader Parajon and Yaser Vado became the first of the recent political prisoners to be found guilty in the Ortega regime’s courtrooms. That was the beginning of a series of political trials that are still ongoing in the El Chipote jail complex. Attorneys and criminal law specialists catalogue these trials as “mockeries” of justice, given the multiple violations to the rights and guarantees of the accused, not to mention the “quality” of the evidence presented against them. The latter, they say, “borders on parody.”

“They’ve condemned and sentenced the political prisoners based on ridiculous evidence that doesn’t prove anything except the regime’s thirst for revenge. It’s evidence that in any real trial would cause the case to crumble in two seconds; what they’re doing borders on caricature,” affirmed an attorney, who asked to remain anonymous for his protection.

Twitter posts; retweets of messages from other people or international organizations; interviews in independent media in which they advocate for international sanctions; police witnesses who contradict each other; cellphone messages: these are all examples of the spurious evidence presented by Ortega’s Prosecution during the trials of the political prisoners.

“None of the evidence presented confirms the accusations. It’s that simple. These are merely political trials, aimed at silencing critical voices,” the lawyer added.

In the cases of Parajon and Vado, declared guilty of the supposed crimes of “conspiracy to undermine the national integrity,” as well as “spreading false news,” the evidence and statements presented against them “are a mockery of justice”, the attorney commented.

Boanerges Fornos formerly a departmental prosecutor for the District Attorney’s office, currently directs the organization Accion Penal [Criminal Action]. He stated: “the Prosecution uses police agents who say whatever the regime wants them to say.” That’s why no civilian witnesses appear in the political trials.

“On the other hand, [they present as evidence] Twitter posts, Facebook pages, interviews they’ve offered. That’s the evidence. If I were on trial there, one more proof of my guilt would be this interview I’m giving Confidencial right now. This – they’d say – is inciting hatred. That’s the quality of evidence they’re using,” argued the former prosecutor, who’s no longer in Nicaragua.

In Fornos’ view, what’s being presented at the trials “can’t even be called evidence,” because “it doesn’t fit in that category.” Given that, he refuses even to call these court processes “trials”: “They’re stage shows, they’re a disgrace.”

A spokesperson from the US State Department also accused Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega of mounting trials plagued with irregularities. “Behind closed doors and with innumerable irregularities, these trials are a mockery of justice and due process,” stated the functionary in an interview with the Voice of America.

“These trials seem to have the intention of terrorizing and discouraging other Nicaraguans from exercising their rights,” he added.

In the trial of youthful political prisoners Yader Parajon and Yaser Vado, the Prosecution’s witnesses were seven police from District Station One who were in charge of the criminal investigation. Three of them offered contradictory testimony, while one responded with seeming reluctance.

Yaser Vado was accused of “propagating fake news”. However, when asked how his posts had harmed the public, one of the police officials responded: “They affected the party”. He didn’t offer any details as to what organization he was referring to, although he clearly alluded to the Sandinista Party.

Among the evidence the Prosecution offered against Suyen Barahona, president of the Democratic Renewal Party (UNAMOS), (formerly the Sandinista Renewal Movement), was the testimony of three police agents. One of them participated in the raid of Barahona’s home on June 13, 2021, when she was arrested without a warrant. Among the supposed evidence these police witnesses offered were books having to do with processes of mediation from the “Office of Alternative Conflict Resolution (DIRAC), a branch of Nicaragua’s own Justice System. These books weren’t even Barahona’s property, but were seized during the illegal raid on her home.

When the defense questioned the book’s relevance to the case, their objections were declared “impertinent” by Judge Ulisa Yahoska Tapia Silva. This, states Barahona’s husband Cesar Dubois, was a partial sample of the “farcical” nature of the trial.

The Prosecution once again relied on police witnesses in the trial against sports chronicler and blogger Miguel Mendoza. One of the seven officials testified that he had participated in the arrest; another declared he had carried out an act of detention; a third mentioned that he searched the journalist’s house and found some electronic devices. “These facts don’t demonstrate the commission of the crime of conspiring to undermine the national integrity,” declared defense lawyer Mynor Curtis.

Four police served as witnesses in the trial against political scientist Jose Antonio Peraza,. They presented as evidence a cellphone, a computer, flash drives, hard discs and a series of documents, but didn’t know how to respond when asked what damaging evidence these items had contained.

In the trial of rural leaders Medardo Mairena and Pedro Mena, the police official called as witness for the Prosecution had supposedly carried out the undercover investigation. He attended the trial covered in a hood, and was referred to as “Code One”.

That police agent affirmed that Pedro Mena was receiving foreign financing for the Farm Movement, but he couldn’t establish the amount of money, the date it was received, nor the exact source of this supposed financing. The undercover official declared that the money came from an NGO, but he didn’t know which. In addition, he declared that they [the police] had been watching the Farm Movement since 2019, without offering any more details.

In the trial of Dora Maria Tellez, former guerrilla leader and founder of the Sandinista Renewal Movement (MRS), now the Democratic Renewal Movement, the District Attorney’s office relied on the testimony of four police. One of them, identified as an information systems specialist, revealed that the police were using web-monitoring software to spy on people’s communications on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Among the evidence the Prosecution cited in the case against Tellez were retweets she had shared of posts by Jose Miguel Vivanco, former head of Human Rights Watch. In addition, there was a retweet from an individual sharing the letter that US Senators had sent in June 2021 to President Joe Biden, urging him to take additional measures in response to the worsening repression in Nicaragua.

The Prosecution also cited an alleged letter from the MRS they claimed was circulating on Twitter, where Tellez’ name appears but not her signature.

Four Twitter posts were also presented as important evidence in the trial of Miguel Mora, journalist and former aspiring presidential candidate for the Democratic Restoration Party [now outlawed]. Three of these posts shared articles from 100% Noticias, the news channel he owned. The items presented referred to sanctions imposed on Nicaragua by the United States and the United Kingdom.

Another Tweet used as evidence against Mora thanked Luis Almagro, Secretary General of the Organization of American States, for speaking out against the aggression that Mora’s wife, Veronica Chavez, suffered in October 2020.

“I thank you for your words, Mr. Almagro, in the name of my wife. Nicaragua hopes that the declaration of illegitimacy of this criminal Sandinista dictatorship won’t fail us,” stated the Tweet the Prosecution presented as criminal evidence.

Paulo Abrao, Brazilian attorney and former executive secretary of the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights, noted that using as proof expressions that form part of the freedom of thought that every citizen has the right to, clearly demonstrates the lack of legitimacy of the supposed evidence being used to convict the prisoners of conscience.

“That’s an example of the great fragility of these trials, which have no legal materiality, nor probatory substance. They have to sift through expressed attitudes that are well within freedom of thought in order to make them square with the idea of actions that risk the nation, the State or the national security,” Abrao declared.

Part of the evidence submitted to prove the case against sports columnist Miguel Mendoza also included some thirty Twitter posts and a few on Facebook. In these posts, Mendoza exercised his right to free expression. Nonetheless, in the trial, an official identified as an expert witness in information technology assured with no documentation that the journalist’s posts “caused anxiety”.

During Dora Maria Tellez’ trial, the Prosecution cited two interviews she had given to independent media sources, and two different occasions when she participated in talks with members of the European Parliament.

According to the Prosecution, the former guerrilla leader: “called for a boycott against Nicaragua and for sanctions” during the interventions mentioned. However, Confidencial has learned that Tellez referred to individual sanctions in these interviews, without affecting the territorial integrity.

In the case of Suyen Barahona, the Prosecution submitted as evidence declarations she’d made to different media sources, expressing her views of the individual – not country-wide – sanctions. As in the other trials, the Prosecutors also presented as evidence her posts on social media and some chats where the opposition leader affirmed her conviction about the need for struggle.

Similarly, in the trial of political scientist Jose Antonio Peraza, the main proof of his “crime” were three videos of interviews he’d given: two to the media outlet Mesa Redonda [Round Table], and the third to Confidencial.

Peraza took part in the first interviews in November 2020, before Nicaragua’s National Assembly approved Law 1055, the so-called “Sovereignty Law”, passed in December 2020. Nonetheless, this same law was used to justify the political scientist’s investigation and arrest. Attorneys point out that the Prosecution was applying a law retroactively, submitting as evidence events that took place at a time when the actions taken didn’t constitute crimes, because there weren’t yet any laws against them.

In the interview the political scientist offered Confidencial, he spoke about the elections, the arrest of the seven aspiring presidential candidates, and the lack of conditions for free and transparent elections with full guarantees. At no time did he applaud or urge sanctions or foreign intervention, as the District Attorney’s Office claimed.

The Nicaraguan University Alliance issued a statement that the evidence submitted in the trial of student leader Lesther Aleman was “fabricated”. During this process, the Prosecution presented as evidence “a false Facebook profile, two videos, and photographs that in no way constitute evidence of crimes.”

Beginning months before his capture, Aleman was denouncing the appearance of false social media profiles using his name, principally on Facebook and Twitter.

Finally, there was the case of farmer Santos Camilo Bellorin, who was found guilty of “spreading fake news” on social media. On February 10th, the 56-year-old farmer was sentenced to 11 years in prison for this supposed crime. At his trial, Bellorin declared that he didn’t even know how to use a cellphone well.

Bellorin’s family members called his conviction “mind boggling”, since the farmer didn’t even own a smartphone and didn’t know how to use a computer. “I believe he’s not even familiar with computers,” declared his brother, Francisco Bellorin.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996. Inició como un semanario impreso y hoy es un medio de referencia regional con información, análisis, entrevistas, perfiles, reportajes e investigaciones sobre Nicaragua, informando desde el exilio por la persecución política de la dictadura de Daniel Ortega y Rosario Murillo.

PUBLICIDAD 3D