10 de septiembre 2018

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Cellphone in hand, Nicaraguans have led and documented an unprecedented civic insurrection.

An image with the tag “#SOSINSS” circulated over the social networks, inviting people to a citizen protest on Wednesday, April 18 against a Social Security reform. A time and place had still not been agreed upon, or at least not been disclosed. The protest’s organizers, a group of young university students and professionals, wanted to avoid having the riot squad and the shock forces be the first to arrive.

On Wednesday afternoon, the self-organized youth revealed the place and the time: the Camino de Oriente area on the Masaya highway, at 5 pm. The social networks entered into action and the information was effectively circulated. A group of citizens of diverse ages arrived at the place agreed upon.

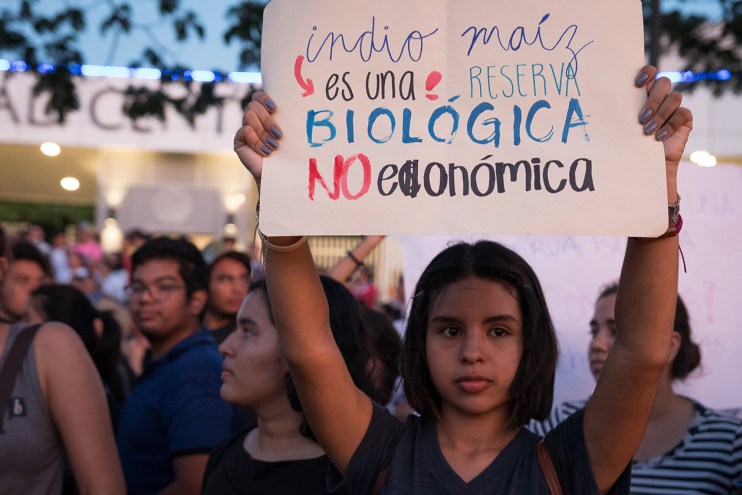

Images of the protest began to be distributed, showing dozens of passers-by honking their horns in the heavy rush-hour traffic along one of the busiest roads of the capital. Some of the faces in the protest were familiar: the same young people who days before were protesting the forest fire that had devoured over five thousand hectares of the Indio Maiz Biological Reserve. Young professionals could also be seen, some still sporting their company ID badges. The protest was growing, and the riot squad and shock forces also arrived at the site.

An hour later, the first images of the wounded, people fleeing the government mobs and of police attacking the citizens and journalists were circulating on social media. The aggression was filmed live, and in addition to the images in the media, dozens of participants were sharing what they were seeing and living through.

The self-organized movement in April didn’t just appear out of nowhere. There are indications that since 2013, at least three generations of students have utilized digital media to change the way of doing politics and have an impact on the national reality. But the massive mobilizations are the “new phenomenon” that has characterized the civic struggle in the last four months plus of the citizen rebellion.

What was the formula that caused the protest called on April 18th to give way to massive mobilizations? Some attribute it to the reach of social media. Although sociologists and experts in social networking insist that not everything depends on Facebook, Twitter or YouTube, they do agree that these networks have been the best channels to convoke, communicate and denounce.

The tag #OcupaINSS, that appeared on the social networks in June 2013 during a prior wave of protest against pension reductions is considered an important precedent in terms of using digital technologies to mobilize and organize the citizens. The digital conversation was transformed into “offline actions.” This was the first demonstration of the “mobilization of conscience,” according to Yassir Chavarria, specialist in communications and digital strategies.

The rural movement against the proposed Canal, led by the group known as The National Council for the Defense of the Land, Lake and Sovereignty, has also used the digital media to disseminate their demands, call for marches and motivate its leaders. However, the location of the farmers’ actions limited the participation of the urban areas that were far away from the centers of protests against Law #840. “In April, the scene of the social actions moved from the rural zones to the urban centers, and that’s a very important difference,” notes Elvira Cuadra, sociologist and director of the Center for Communications Research.

Guillermo Rothschuh, media specialist, feels that the socio-political conditions seven years ago weren’t strong enough to unleash a massive mobilization like that of the recent civic uprising in Nicaragua. Adding to this context, has been the increasing use of social networks to transmit information in real time.

One of the groups with the longest experience in the digital world is the feminist movement. Elvira Cuadra identifies a large cohort of young feminist activists who’ve been in different places and have utilized digital activism most consistently. They’ve carried out both online and offline actions to demand changes in the system and defend the rights of women, who are also part of the collective demands of the self-organized movements.

“For those who say that we youth are wrapped up in the social networks, here we are,” they affirmed. Photo: Carlos Herrera

Madelaine Caracas of the University Coordinator for Democracy and Justice, recalls the beginning of the April protests with the demand for action to stop the spread of the forest fire in the Indio-Maiz Biological Reserve.

“The digital platforms helped to bring together the street protest. It was totally unanticipated, but the networks served not only as a way to broadcast information, but also for articulating and uniting different groups of people,” Caracas relates.

The communications strategies and the call for the Indio-Maiz protests were all carried out via group chats. That first April demonstration ended in repression while the group of young people were marching towards the monument to Nicaraguan boxer Alexis Arguello.

On the afternoon of April 16, Roberto Lopez, president of the Nicaraguan Social Security Institute, made the surprising announcement of a substantial increase in the Social Security quotas. The next day, the social networks again went into action, and the groups that had coordinated the Indio-Maiz mobilization came up with the idea for a civic action against the proposed reforms.

“The repressive acts registered live on April 18, were captured in real time. They revealed the aggression unleashed against the peaceful demonstration and helped create empathy for the realities of that moment,” declares Yaser Morazan, a political activist in social networking.

“This was a trial by fire for the social networks,” assures Guillermo Rothschuh. Proof of their effectiveness lay in the massive mobilizations that sprung up all over the country. These were not only a reaction to the immediate repression, but also reflected a tipping point in events.

The precedents included the repression of different civic demonstrations, the cases of corruption, nepotism, control over the media, and the messianic build-up of the figures of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo. These frustrations all contributed to a “snowball effect”, that awakened the population.

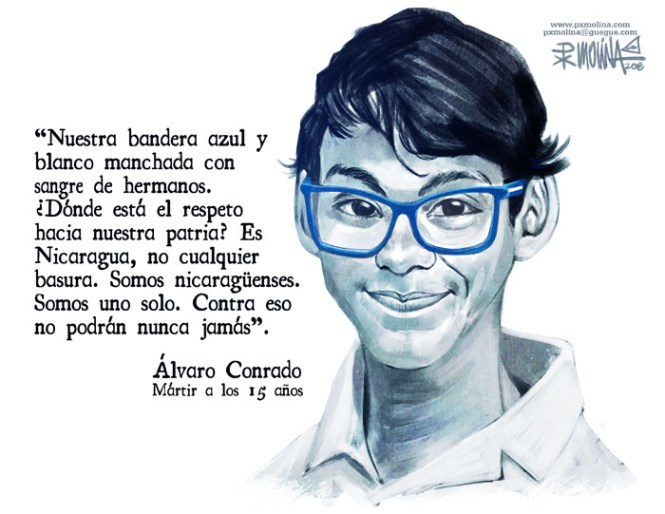

“I watched the death of Alvarito Conrado in real time. How many other people saw it? I don’t know, but I was watching the live transmission and some of those videos had 10,000 people watching,” recalls Elvira Cuadra. These transmissions showing events as they are, arrive more quickly and immediately than reading them in the newspapers, listening to them on the radio or watching them on television five hours later.

“Facebook Live” videos have become a determining factor in getting people out on the streets. Cuadra remembers that on April 18, after watching live the aggression unleashed against the demonstration on the Eastern Road, many people immediately went out to join in. That couldn’t have been achieved without the social networks. “What happened in April and what’s been happening in the country is like those stories where you open a door to a new dimension. In this case, we’re opening the doors to a new dimension of social reality with a potential for change and for new communications processes, via the use of digital technologies,” Cuadra says.

The citizens have taken maximum advantage of their cellphones and internet connections, principally the youth who find new ways of expression every day though the digital platforms. “The youth on the social networks post concrete events, and these events generate information that the rest of us process. From them, we form our criteria that later become our positions. In other words, I become conscious of a situation even if I wasn’t there but I witnessed it on social media. Then I make my decision. I see the problem, I don’t agree with what’s happening, and I want to demand change. Such demands to power are principally carried out on the streets,” explains Yassir Chavarria.

“Live sharing was fundamental in encouraging, mobilizing and awakening more people to what was happening,” Madelaine Caracas states. “The social networks and the new communications media have been the eyes for many who don’t live in Managua, Leon, Masaya, Matagalpa or the other places where there’ve been protests, because the government controls at least 70% of the communications media. So, the networks have been those eyes,” the university leader reflects.

According to digital activist Yaser Morazan, the government knows very well the power that the social networks wield, to the extent that they’ve been desperately trying to control these spaces in different ways. “The internet has become the oracle that the population consults. They believe ever less in vertical opinions and social media has become an alternative for the exchange of ideas and information,” Morazan points out.

The citizens aren’t the only ones who’ve taken advantage of the digital tools to transmit relevant events. Reporters and the traditional communications media have had to step to the rhythm of the protests and make maximum use of live transmissions. “In Facebook Live, you’re clear that they can’t lie to you, because there’s no possible way of editing them. The impact of this is so great that it’s a highly valued medium of communication,” points out Guillermo Rothchuh.

“The government contributed to reactivating the networks and energizing the other media. Their mistake in censoring the”100% news” television channel and for a short time Channels 12, 51 and 99, immediately converted the online networks used by these media outlets into valued and privileged corners of information,” Rothschuh indicates.

There’s also a phenomenon that Rothschuh has observed in these four months. “Those journalists who not only publish their pieces in the traditional media, but also post them on social media have a greater impact. This indicates that the massive use of the social networks is a relevant historical and political fact that won’t be undone.”

Protests in Nicaragua. Photo: Carlos Herrera

In 2011, during the “Arab Spring” in Egypt, internet connections and cellphones were prohibited. Similar policies were instituted in Tunisia, Libya, Yemen and other Arab countries in conflict. As in Nicaragua, the use of cellphones and social media played an important role in transmitting and disseminating the demonstrators’ demands. The images and transmissions produced by the citizens and reproduced on the social networks functioned as an echo chamber.

Yaser Morazan believes that there’s a latent risk of an attempt to control these networks in Nicaragua. “However, I firmly believe that human freedom, by its nature, will always find ways to express itself. The young people demonstrated this at the end of the 70s when they defeated a dictatorship without social media,” Morazan said.

Young Nicaraguans get their information though the social networks more than through the digital media. “The main motor that regulates the dynamics of social media is credibility and emotional empathy. An outworn regime like this one lacks both credibility and human empathy for communicating its ideas, especially because it uses a language of hate that attacks those they feel are bad,” Yaser analyzes.

For Elvira Cuadra, however, the government no longer has the capability for such control over the social media. She feels that the government lost the hegemony of discourse and control of the messages right from the beginning of April. “Every government speech or attempt to stigmatize the movement has ended up completely boomeranging; I refer specifically to Rosario Murillo and her descriptions of the movement. There hasn’t been one expression of those she’s used, that in the end hasn’t been converted into a counter-discourse and backfired on them,” Cuadra reflects.

Yassir Chavarria thinks it’s more important to point out the changes in the government’s strategy. “They’re going to create more effective platforms for their messages and communications, but I don’t have any evidence to tell you that we’re going to have a kind of Venezuelan approach that limits access to technology. Also, the internet service providers would have to be coopted. Would they be open to having their own businesses affected?” Chavarria questioned.

There’s an accumulation of experience that tells us what to do in the face of scenarios like that of Turkey, Egypt or Venezuela. Information specialists are always evolving new ways of getting around the censorship imposed by authoritarian governments.

Guillermo Rothschuh believes that the Nicaraguan government is weak in the face of these media players. He believes that control of the social networks and other digital platforms is impossible to achieve. “The battle is also waging via the social networks, and I consider them the first battle front. The citizens have discovered that their cellphones are their arms in this political struggle; in the battle to win hearts, it’s precisely the social media that’s in first place for winning over the people,” notes Rothschuh.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D