Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Nicaraguan cartoonist Pedro Molina says the country’s paramilitary groups are like ISIS.

La cacería-PxMolinA

Pedro Molina wants you to know that what’s happening in Nicaragua is not a civil war.

“There aren’t two armed groups facing each other,” he wrote in an email exchange earlier this month. “This is a massacre of an armed state against unarmed people.”

More than 300 people have died in the Central American country since protests broke out in April, according to human rights groups (some organizations put the figure closer to 450). Since then, hundreds have been kidnapped or imprisonedand hundreds more have fled the country.

The protests started after President Daniel Ortega proposed reducing pension benefits. The government responded with a swift crackdown, and police and pro-government mobs attacked protesters, which prompted additional marches. Ortega eventually withdrew the proposal, but rallies calling for his removal had already spread across the country.

Pro-Ortega paramilitaries have been accused of killing and abducting hundreds of civilians in recent months.

Ortega and his vice president—and wife—Rosario Murillo have accused protesters of trying to stage a coup.

Ortega has been in office since 2007, and he has tightened his grip during that time: his party controls all branches of government, he has eliminated term limits, and in 2016, his wife, Rosario Murillo, became vice president. Ortega denies having ties to violent paramilitary groups and has accused protesters of trying to stage a coup.

Molina, 41, is one of Nicaragua’s best-known illustrators. He’s been in the trade for over 20 years, and said his first-ever caricature was of Ortega, back in 1990. Ortega, 72, rose to prominence in the 1970s as a leader of the Marxist Sandinistas, a revolutionary group known by its Spanish acronym FSLN, that ruled the country from 1979 to 1990.

“I have never trusted him,” said Molina. “He always seemed to me like a cold manipulating liar capable of doing [any]thing to obtain and retain power.”

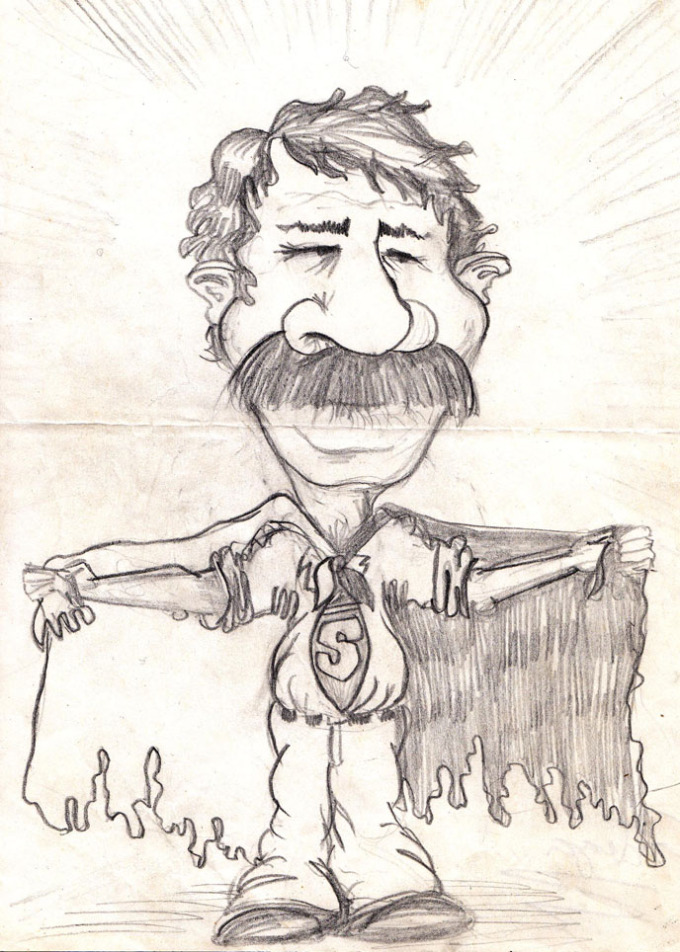

In a sketch he drew in 1990, Molina depicts Ortega wearing a tattered Sandinista flag.

In that early cartoon, Ortega is depicted as a superhero donning the red and black Sandinista flag as a cape, which is in tatters. “Somehow at that time, a part of me already felt he was going to destroy FSLN legacy,” he said.

The Nicaraguan cartoonist has published his work depicting international figures like Nelson Mandela and Pope Francis in publications like the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post, but today his main focus is on his native country.

Molina often compares pro-Sandinista with ISIS.

“As a citizen, I also feel the anger, the frustration, the pain of every Nicaraguan, and that shows up in my work too.”

He often depicts pro-government paramilitary forces as terrorists, even invoking ISIS. In one cartoon, a group of masked men travel in a pickup truck, wielding AK-47s and Sandinista flag transformed to resemble ISIS’. “Both are illegal militias based on hate toward those who don’t think like them,” he said, adding that, like ISIS, many of the pro-Ortega paramilitaries are heavily armed, cover their faces, travel in flag-adorned pickup trucks, and target civilians.

In another sketch, he writes about the normalization of state violence. “Is it normal,” he asks, to be unable to leave the house “for fear that you could be kidnapped or killed by paramilitaries?” Or, “to label priests, doctors, and students as ‘terrorists’?” He references a widely circulated video that depicts police officers dancing and singing “Daniel se queda” (Daniel stays) following clashes that reportedly left at least two children dead as well as the firing of around 100 doctors from public hospitals after they treated civilians injured in protests.

The cartoon series ends with a deranged-looking Ortega, drooling and wrapped in a straight-jacket. “You would have to be abnormal to consider all this ‘normal’,” the caption reads.

Molinas said as a cartoonist, his job is to make people think, and maybe laugh. “We often draw situations that look hard, crazy, irrational, unbelievable,” he said. With each day that goes by, he said, even his most outlandish cartoons are beginning to look like the reality in Nicaragua.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D