5 de marzo 2017

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

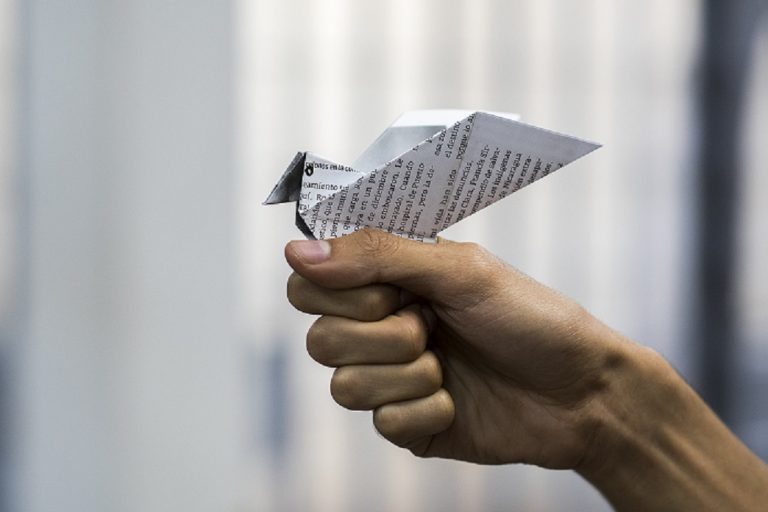

Independent media continues to have credibility, while the TV stations make use of sensational stories of violence and trivial propaganda.

When President Ortega speaks, the independent media must keep quiet. That seems to be the premise for spreading government speeches and news announcements. Last Tuesday, when Ortega was supposed to give his government report in front of Parliament after 8 years of never showing up, independent media outlets and foreign reporters were banned from entering the room where legislators from his Sandinista Front party, and the minority parliament members that collaborate with them, were allowed.

This strategy forms part of a media policy which has been imposed ever since Ortega returned to power in 2007, and this has had a detrimental effect on national transparency. Public information is not made available, independent media outlets aren’t able to ask questions, and presidential press conferences are nil.

“The main problem is the limits on information; we are seeing cases where information should really be public and nobody talks about the Public Information law, which is wet paper, and isn’t complied with. We are reaching nevels where you can follow all of the procedures put into place to gain access and then the official will just ignore you. That shows you the extent of the problems there are in journalism in Nicaragua today,” notes Moises Martinez a journalist from La Prensa newspaper.

The Public Information Access law, which was passed by the National Assembly in 2007, has hardly been implemented at all. Patricia Orozco, the founder of the radio show Onda Local, explains that “you can go onto the City Halls’ websites, search for updated stats on municipal investment and find anything.”

“You’re not on the list”

The order extends to all government offices, where officials have received guidelines not to give information to journalists who “aren’t on the list” of media aligned with the government’s propaganda machine. And when the official identifies a journalist who works for the independent press, that’s reason enough for them to cancel interviews or ask for them to delete statements they have given beforehand.

Public relations officers in every State institution close their doors to journalists, even though what they cover with their reports is in the Nicaraguan people’s public interest, such as in the case of the Health Ministry (MINSA).

Melissa Aguilera, a journalist at Diario Hoy, remembers that on several occasions she hasn’t been allowed to enter public facilities and had been refused interviews.

“When I want to interview people at City Hall, it’s a difficult task. They say yes, that I leave my number and that they will tell me when to come, but they never call me, they never give me any information. The same thing happens with MINSA,” Aguilera said.

Roy Moncada is the journalist in charge of covering the Managua City Hall for the La Prensa newspaper and even though he has been invited to events from time to time, it is normally very hard to ask questions about how the city is managed.

A contagious disease

Journalists think that this disease is spreading to business spokespeople. When investigative reporters ask uncomfortable questions about business leadership, the worse side of government officials comes to light, says journalist Moises Martinez. “They are hostile or annoyed when we ask questions that they don’t like,” he pointed out.

Martinez warns that there is a tendency to discredit the press’ professional role, when they try to carry out an investigation. “They say that we work for a cause or are the spokespeople for a political movement without realizing that what we seek out are the greatest number of viewpoints on one story,” he says.

Luiz Galeano is the director of the TV and radio show Cafe con Voz, and knows firsthand just how difficult it is to keep a program up and running when few businesses want to offer advertising.

“I began in radio and I continue using radio because radio stations have joined up with Cafe con Voz and continue to broadcast it, but it is really hard to get an ad in this present situation. It’s very hard because when you say you talk about politics, there are companies which say that they don’t like to talk about politics,” Galeano tells me. And he adds that “the problem here is that business people have to realize that the only real ally they have once the government begins to humiliate them, is the media. When they knock on the door and don’t find it, then they’re going to say: I made a big mistake. Where are the people who can defend me?” Galeano warned.

Government publicity and family-owned media

Economic suffocation has been one of the pressure points which has affected the media the most over the last decade. Patricia Orozco recalls that you could get publicity ads from municipal governments before, and it was a lot easier to keep shows going. However, every since the Comandante came into power in 2007, the situation has worsened. The Onda Local radio show receives donations from private individuals who give small sums of money so that they can continue to be broadcast and don’t disappear.

Orozco even said that there are times when they are late in paying bills because they don’t have all the money they need, but they always end up paying.

They don’t receive government ads and are mainly funded by NGOs which, allegedly, still believe in the project. “Paying staff is the last priority. We have decided this among us as a team.” Orozco said.

Government advertising is mainly used to support the media owned by the Oretega-Murillo family, and some government media outlets, and completely refuses publicity for press that criticize the powers that be.

The media apparatus which serves the government has grown significantly since 2008, to the point where they now control eight out of the nine TV channels transmitted.

The Impact in the Concentration of TV Ownership

Nicaraguan TV is dominated by two groupings, Mexican businessman Angel Gonzalez, also nick-named “The Ghost”, and the Ortega-Murillo family.

Between them, they own eight out of the nine TV channels. The ruling family manages the frequencies of channels 4, 8 and 13 and over a dozen radio stations as private companies, via five of the presidential couples’ children. They also control channel 6, which belongs to the State, but is managed by Aaron Perarly, the leader of Sandinista Youth.

Meanwhile Gonzalez has control of channels 2, 9, 10 and 11. The director of Media Watch, Professor Guillermo Rothschuh, explains that Gonzalez and the Ortega-Murillo family also have TV licenses on UHF. At least the one we know about is 41 (50 on cable where RT news appears) and Gonzalez has also been authorized to manage RTV on subscription (Nica Dream). With regard to VHF, the channel 7 frequency, previously used to repeat channel 2’s broadcast, was divided into two: one remained an antenna for the country’s interior and the other as a separate frequency for the Pacific coast.”

Alfonso Malespin, an expert in media, said that the concentration of media in the country’s interior regions is even worse, because the government has closed or decided to reassign some frequencies to cable TV channels.

This is due to the fact that the sale of channels has slowed down because they control nearly all of them. “What they’re doing now, is repositioning channels which are related to the local cable company’s grid, especially Claro,” the expert said.

The control of the majority of channels in the hands of two large business and political players has its consequences for the Nicaraguan people. These include the deterioration in the quality of information and public debate. In these media, news coverage of public interest matters have been replaced with an advertising blitz of government propaganda, sensationalist journalism and celebrity or frivolous news.

On the one hand, reporters have seen how spaces for practicing critical reporting have closed, and on the other, how the general population now has less sources of information to inform themselves.

People on the street feel like the media often doesn’t really deal with the problems that affect them, or they are surprised when they hear some government media outlets say that everything is fine when they are experiencing great financial constraints.

Oscar Melendez works as a driver and it’s becoming harder and harder for him to buy basic products, however, he insists on the fact that Ortega and Gonzalez’s media only talk about a Nicaragua where there is a great deal of success. “There are people who say that the country is stable, but that isn’t true,” he complains.

Other citizens realize that journalists today are being constantly harassed and warn that they don’t like this one bit. “I think they are doing a good job, the problem is that a lot of people criticize journalists and the media. People harass them and I don’t get it, because it’s their job to get the news into people’s homes,” Freddy Guzman explained.

Battle for credibility

Alfonso Malespin believes that the information which results from surveys about how people view independent media is contradictory. “Surveys say, on the one hand, that people value freedom of speech and that then they say that don’t see the creation of media monopolies as an important danger. They don’t see the great danger there is in having a family or a small group of people controlling the media, especially TV and radio.

Guillermo Rothschuh warns that in spite of the number of media outlets which share the same discourse, this won’t have any effect on people as they don’t deal with their everyday problems. “They’re committing a mistake and that’s to believe that the media which makes government discourse their own will be effective because there are many of them. But, the handicap that official and quasi-official media has is that they aren’t very credible in the eyes of their readers and viewers,” the journalism professor explains.

Rotsen Lopez, a reporter on Channel 12 also warns that journalists should fight to open up spaces. “We have gotten used to not being invited to the FSLN conferences. We’re used to asking isolated things at the Cosep business council or that a religious leader only talks about what they want to. I believe that we aren’t realizing, as reporters, just how closed these spaces are and we aren’t doing anything to open them.”

The future of journalism over the next five years of Ortega’s rule looks bleak, and the situation doesn’t look like it will change much. Reporters warn that everything will be hard, but they are convinced that people really value quality independent investigative journalism provided by the few media outlets or shows which aren’t subordinated to government discourse.

This has been one of the strengths that Orozco sees in the Onda Local show. “It really depends on the quality of work we do. This situation has helped us to creatively seek out new sources,” she said.

Meanwhile, Martinez predicts that quality journalism won’t disappear, as there will always be professionals who decide to monitor the government. “There will always be people who are intent on making good journalism. It will be harder for us. We always hope that new generations will value the importance of independent media,” the La Prensa reporter said.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D