Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

One of a series of recorded interviews, intended to encourage personal memories, and to learn from the exercise of letting out “what hasn’t been said.”

Rosalia is her alias. She is a doctor and 44 years old. Our daughters go to the same school, and one afternoon we began conversing about the current situation in the country. In the course of this, she told me some pieces of her incredible story, a story I wanted to know more about. When months later I described to her my project of collecting memories, she told me she wanted to participate.

She’s one of my generation, and I feel that she represents the feelings of many of my friends who threw their whole selves into the work of the Revolution, from the time we were children. However, her particular story goes back further, beginning slightly after she turned four. Her testimony speaks of cycles of mourning, silence, awakening and emancipation.

“I turned four on May 4, 1979, and my father was killed on May 12. It was a Saturday, I remember…the massacre was at Xiloa [a lake on the outskirts of Managua]. We were living along the Old Leon Highway, and I remember that Sunday becoming aware that something was happening. That’s why I have it so present…

“We had a lot of weapons in the house, and my father was in charge of them. Later, they explained to me… that he was in charge of the insurrection plan for Managua..

“He was collecting arms, and also gathering together Molotov cocktails. We had a ton of bottles – there were bottles and more bottles, some of them full of kerosene – and also the weapons. On that Sunday, the memory that’s clearest was of the horrible noise of those plastic bags, since they were very stiff. I was helping my mother to stash the weapons in them, because my Mama [was alone] with us two little girls and our uncle…. As we put the weapons in the bags, they made a noise like crrack, crrack, and then we’d bury them in a hole behind the house we used for garbage. [We also buried] all the bottles, and anything that would be dangerous.

“After that, we went immediately to the Mexican embassy to ask for asylum: my Mama, my sister and I. From there, I don’t remember anything else except that two days later my grandmother on my father’s side came to say goodbye to us, crying.

“At that moment, no one had told me that my Papa was dead, or that he’d been killed. We children… weren’t taken into account. If you ask me if I have any recall of my Mama sitting down with me and saying ‘Your Papa died’, or something like that – absolutely not. The one who told me when we were already on board the airplane to go to Mexico, is my older sister. My older sister, who was seven, found out that something had happened, and she buttonholed my Mama and said, “My Papa is dead, isn’t he?” and my Mama said yes. So, she came up to me and told me: ‘My Papa’s dead.’

“Then it was the eighties, but instead of being a happy time because the Revolution had triumphed, I felt that I’d lost my mother in that process. She literally became another person, a person who had to show the world or the Sandinista Front or the people [that] she’d made a commitment. Maybe she felt she had a promise to fulfill for her dead husband, so that she had to give everything for the Revolution. When I say everything, I mean everything: after we came back to Nicaragua, we didn’t even see my mother go by.

“She literally left us with our grandparents. So, from there on, the memories I have of the eighties is that now I don’t have a mother or a father, but I do have two incredible grandparents. They were the best grandparents I could ever have had (tearfully), but I thought that it was somehow wrong. At some point, I thought: ‘How can it be that I’m being raised by my grandparents? Why don’t I have a mother and father?’ It’s the only thing that always brings me to tears, remembering how good they were, because they were two incredible people. My grandmother was repeating her own story with us: she had lost her father in the war of the Liberals against the Conservatives…and her own story of being an orphan, and also of living in poverty was terrible.

“I lived with my grandparents from 1980 until 1987, when we began living with my mother. She put us in a different school, since she didn’t want us to live in that bubble. We’d been studying in a private school that my grandparents paid for, but when she came for us she told us: ‘You have to go to a public school’, and ‘you have to belong to and get involved in the Sandinista Youth’ and all the things that were part of the struggles of the eighties. And since I felt that commitment… I said ‘yes, I can do that’, and we joined the Sandinista Youth and studied in the public school.

“Definitely, it was another life. The kids there were intense. We got around on the public bus, or walking; no one came and picked us up from school, no one watched over us. We were part of the Sandinista Youth, of a branch that was pretty strong, and [its members were] often chosen by the regional cadres of the Sandinista Youth to become leaders. So, we received a lot of training, we were often taken to do political work, and we did a lot of neighborhood work…

“Can you imagine how crazy? To have sent us to the neighborhoods, when I was 13, to recruit kids for the Military Service. Me, at 13, trying to convince a boy of 16 to volunteer [for the army]? We didn’t want to see that when we went out onto the streets as members of the Sandinista Youth, no one came out of their houses. Now I remember how the people despised us, but in that moment, I didn’t want to see it.

“As a member of the Sandinista Youth, it fell to me… to tidy up the graves of the Heroes and Martyrs from one of the massacres, I think it was the one that took place in San Jose de las Mulas in 1984, when there were a whole bunch of kids killed.. Seeing how still – in 1988, four years later – the Mothers would lie down on the graves, crying for their sons, had a great impact on me. At that moment, I asked myself many questions: in other words, I wasn’t so blind anymore. They never awarded me the militancy in the Sandinista Youth, although by 1989 I was fourteen, because I was very much a questioner.

“I had grown up with a critical sense, and I discovered that there were things that didn’t seem right to me, even within the leadership of the Sandinista Youth. I saw the sexual harassment from a bunch of old leaders, who would go after the girls of 15 or 16 in the group. One of those girls experienced a horrible level of harassment, so bad that her father and mother had to go to talk to the old guy.”

I asked Rosalia about her process of mourning the death of her father, because he had been one of the heroes of the revolution who represented the ultimate sacrifice for the nation, and it seemed significant to me that it be precisely his daughter the one questioning the Sandinista model of government.

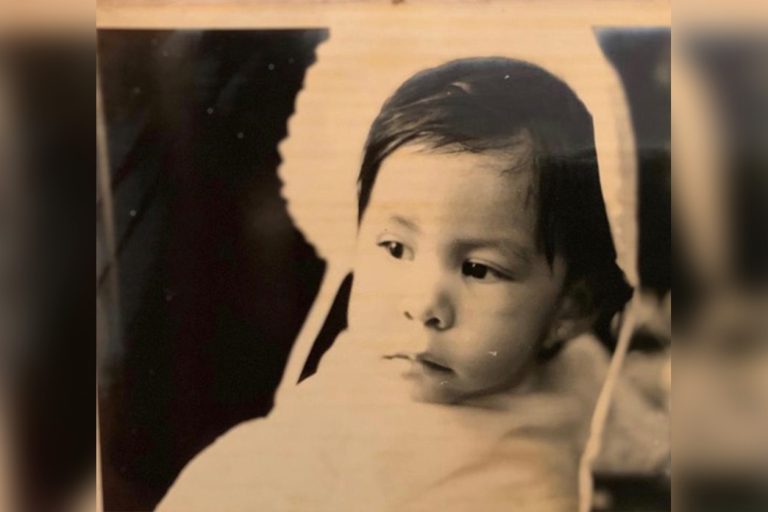

“With my father, I probably don’t have anything more than a sense of his absence… because he was never an important figure in my life. They tell me that when I was a year old, he was thrown in prison. He was imprisoned together with Carlos Fonseca and Tomas Borge and he was there for around 6 months. They tortured him terribly. They got him out of jail, but he could no longer return to normal life, so he never lived with us, he’d only arrive sporadically at night. So, he wasn’t an important figure in my life, he was really a figure of abandonment, of absence, instead. My mother has never told us how everything happened.

“So, speaking about memories, for my mother, the topic of my father became a forbidden theme: she can’t talk about him, ever. She has something like a wall there, and we could never touch on that topic. So, I grew up with the big deal about [him being] a hero and martyr who gave his life for the Revolution, etc., but he really wasn’t a father. He wasn’t a father to us, so it was more like [he was just] a political figure and all the praise, but he wasn’t anything in my life, just the example that had to be followed.

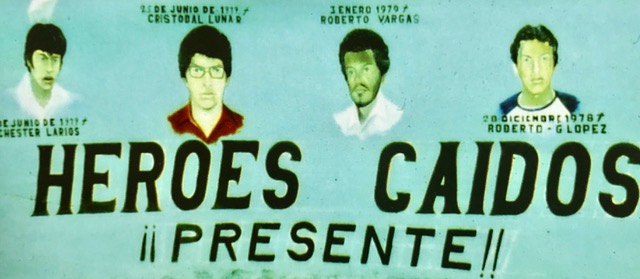

This image of the fallen heroes comes from a mural painted in 1979. The photo was taken from the book “La Revolucion es un Libro y un Hombre Libre” [“The Revolution is a book and a Free Man”], published by the Institute for the History of Nicaragua and Central America of the Central American University.

“Many years passed and one day – I’m talking about 2014 – I discovered that I hadn’t reached any closure with my Papa. At that time, I was 39 and I didn’t know who my father was, we had never had any closure with him. So I told my older sister: ‘Lets’ hold a memorial gathering for him…’. We made out the invitations between us, and we collected photos, collected his history from the time he was a child; we spoke with his brothers and sisters, with his friends. And on May 12, 2014, when he had been dead for 35 years, we held this memorial gathering.

“People came who had known him during the struggle of course – the theme of his participation in the struggle had to come out – but also memories about his life as such came out: as a child, as a son, as a brother as a husband. At the end, I spoke. And I finally, took my leave of him, and it gave me peace and serenity. It’s like I was finally able to bury him. I knew who he was, and I was left feeling at peace with that.”

Disillusionment with the FSLN

Rosalia suffered disappointments that began to erode her affiliation with the Sandinistas. One came in the year 2000, when she wanted to study for a specialty in dermatology. She came up against the mediocrity of the doctors who were in the party, who blocked the opportunities for her [for political reasons] even though she had excellent grades and reports.

A group of protestors destroy a billboard of President Daniel Ortega and Vice President Rosario Murillo. Photo: Carlos Herrera

Other disappointments included Zoilamerica Narvaez’ [1998] denunciation of the sexual abuse she had suffered from childhood at the hands of Daniel Ortega; the candidacy of now Vice President Rosario Murillo; and the Ortega’s very evident squandering of resources.

“So it was, that when this moment (the April 2018 rebellion) arrived, my eyes weren’t so blindfolded…

“In a decisive moment of the repression, we had blue and white flags and balloons in the house. Then a very particular situation arose, in which we issued a communique as parents of the children at school. The next day, there were six pick-ups full of hooded paramilitary and all that…

“Suddenly, I thought – ‘What do I have here that could be compromising?’ My husband had four guns in the house, all with permits – because on the farm they had arms. Can you believe it?! I went to hide the pistols, I went to grab the balloons and the flags, and go to bury them in a garbage dump behind the house. All of a sudden, the memory flooded back to me of helping my Mama the day after they killed my Dad, of going to bury the arms.

“I said to myself: ‘What craziness is this? What am I burying – my flaaaggg, my blue and white flag. I’m going to bury the flag of my country, so that these demons don’t find it.’ Suddenly, a tear dripped down, because I said: ‘This is the last straw… We’re burying balloons and flags.’ And those who were my mother and father were burying pistols and Molotov cocktails. What kind of a contradiction is that?…

“My mother has cried terribly. I see how terribly this has struck her, because she knows that there’s no logical argument with which you can defend this.”

—–

This testimony is part of a series of interviews that open a window onto the memories related to the Sandinista Revolution, as well as on the things we’ve lived through in Nicaragua since April 2018. The only objective is to help encourage personal memories, and to learn from the past through the exercise of letting out “what hasn’t been said.” The interviews were realized as part of the final project presented for a post-graduate course in Memory and Communication, offered by the Central American University in 2019. You are invited to draw your own conclusions.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D