21 de enero 2019

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

“The majority of those within the Sandinista Front want there to be a dialogue, but there’s a fear of talking about it…”

“The majority of those within the Sandinista Front want there to be a dialogue

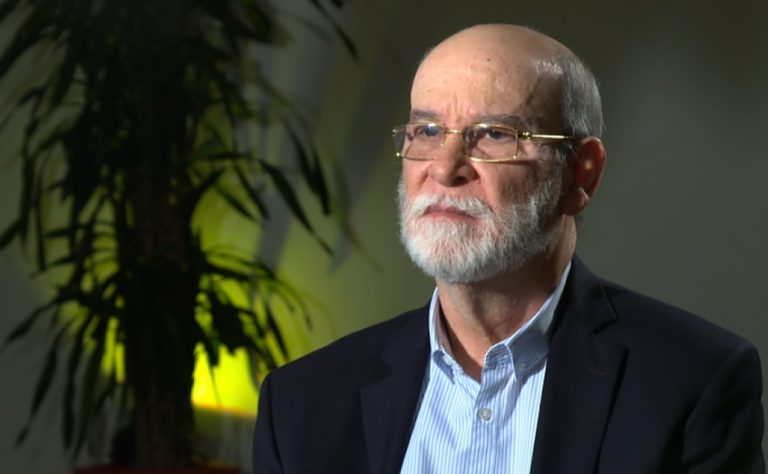

Former Supreme Court judge Rafael Solis spoke for 54 minutes before the cameras of the weekly television news show Esta Semana, giving the reasons behind his political rupture with the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo.

Having renounced his public and FSLN party positions, Solis now advocates for the annulment of the ongoing trials against more than 500 political prisoners and called for the creation of a “Truth Commission. He maintains that if a National Dialogue resumes the topic of justice can’t be left out.

Ten days after resigning from the Supreme Court and the FSLN, Solis insists that Ortega “has no will to negotiate.” He warns that within the FSLN there’s no movement that would openly pressure him to do so, although he says the majority of the Sandinistas favor a dialogue.

The ideologue behind Ortega’s unconstitutional reelection in 2011, acknowledges his “political responsibilities” as magistrate on the Nicaraguan Supreme Court and a political operator of the FSLN. Solis denies having negotiated with any foreign government, and argued that his resignation is “a personal decision ” He also called for a dialogue to avert a civil war.

This is a fragment of my interview with him in Costa Rica.

Some functionaries have resigned from the government citing their health conditions or personal problems. In your case, you announced publicly a political rupture with President Ortega and the FSLN. What was your objective in doing this?

I did consider the possibility of doing it in another way. However, seeing the position over the last few months, and especially the latest one – the President’s New Year’s speech [where it was apparent] that there wasn’t going to be any dialogue and that the doors were practically closed to any type of negotiation – I made the decision to take the political road instead via a public letter contemplating a series of situations with which I didn’t agree. Also, I wanted to sound a warning that resuming the dialogue was important or the country could find itself engulfed in violence. It seemed to me that a call for reflection would generate a greater effect than a simple resignation for health reasons.

In your resignation, you state that on at least two occasions you proposed to President Ortega alternatives or solutions to negotiate a political way out, but that these proposals weren’t considered. What were those alternatives?

There were more or less five alternative proposals that I made upon returning from Mexico at the beginning of the Dialogue [in May]. I called him [Ortega] on the phone and he told me: “Send them to me, of course I will [take a look].” I spoke with Rosario, I spoke with both of them. Then I proposed a variety of possibilities that involved constitutional reforms as an alternative to explore.

Obviously, if early elections were to occur, they’d have to be accompanied by constitutional reforms, but I suggested taking advantage of that opportunity and broadening them to include topics that were on the table, having to do with the concentration of power, and to go back and expand the faculties of each of the state powers a bit.

I also laid before them the possibilities that they would have to begin with an electoral reform, and that we should opt for the route of electoral reforms, including a new Electoral Council, taking advantage of the fact that the current [magistrates] term periods were almost up.

Another thing I proposed was the possibility of a referendum on whether or not to move up the elections. That would be a sounding board, because a referendum is a consultation on the same topic. If you lost the referendum, then, clearly, you’d have to move next towards early elections.

Rafael Solis being interviewed by Carlos F. Chamorro on the Esta Semana (This Week) TV program. Photo: Elmer Rivas | Confidencial

What were President Ortega’s considerations?

He did call me back, and he told me that he was aware of the document, that he approved of it, that he was going to call me later to discuss it. Rosario also said that she had seen it. “It seems fine to me,” she said. “The most important thing is that we stay firm in the decisions that we’re making. Later we’ll discuss all the proposals that you presented.” The reality is that throughout the whole time that the crisis lasted, there wasn’t any opportunity to converse about these matters.

Was that before or after the encounter they had with Caleb McCarry, the emissary from the United States Senate, and the one that they later had with the bishops?

That was at the end of May, before those meetings. The information that I had was that he’d told the emissary that, yes, they might be willing to move up the elections, but he later made the opposite decision, not to move them up. The bishops also proposed advancing the elections and even set the date for the last Sunday in March. By then I believe he’d already made the decision not to continue with the Dialogue.

To what do you attribute the hardening attitude of Ortega and Murillo that you mention in your letter, and which later led to “Operation Clean-Up,” the attack on the bishops as mediators, and finally the imposition of the state of terror that you describe?

It’s very hard to know what goes on inside someone. Maybe the Dialogue also began in such a violent manner that it caused them to react very defensively. If you recall, in the first session of the Dialogue, some of those that spoke, especially the students, stated that they weren’t going to talk about alternatives but about his departure from power, how it was going to be, etcetera.

It was, I believe, a manner of tackling things that perhaps hardened their position. They probably thought: “What these people want is to get rid of us, for us to leave. They’re not thinking about a negotiation.” In the face of that situation, despite the fact that the Police were being asked to hold back, as they were for a time, another possibility then began developing: that of putting an end to the roadblocks in another way.

To be objective, looking at things in retrospect, I also believe there was some intransigence on the part of those who were in favor of the roadblocks. Although publicly the private sector and the bishops stated that they didn’t control the people at the roadblocks, yes, there was a relationship there, and they felt that through the pressure of maintaining the barricades and keeping the country paralyzed – because there came to be almost three hundred of them all over the country – they were going to get rid of Daniel. They were wrong there, because, obviously, that wasn’t the way.

Perhaps there was a lack of vision, in the sense that the problem of the roadblocks could have been dealt with more flexibly. because in several meetings the government and the government delegation insisted that the roadblocks had to be lifted in order to advance with the dialogue.

But what came next was “Operation Clean-Up” and the paramilitary bands…

I agree with you.

And hundreds of political prisoners,

Yes

The curtailment of all public freedoms…

Yes. That’s what I’m pointing out – the excessive use of force. Their position hardened, and they didn’t go back to the Dialogue. But I believe that the prevailing perception was that they [the demonstrators] wanted was to get rid of them. That’s how the thesis developed within the government and the ranks of the Sandinista Front that what was behind all this was a Coup d’etat, instead of a protest begun in a spontaneous way that later gained strength because of the accumulation of a series of factors from previous years.

Maybe they actually believed that what lay behind it all was an attempt to defeat them, rather than opening a possibility for negotiation. It could be that they exaggerated the arms that the others had, their capacity to organize people, and, well, they opted for the hard way, and that’s how it happened.

But it was the government that unleashed the repression and terror against the population and that in the end established a de facto state of emergency.

In the end it came to that, but that thesis [of a coup d’état attempt] is what the government has invariably maintained in the international forums and within the country. It could be that deep within some of those in the Frente there’s doubt about whether or not there was really a failed coup. I’m convinced, analyzing things carefully, that there wasn’t, but others might think, “Yes, there was.” These weren’t things that we discussed in political circles or in the Court. Sincerely, I believe that there was no such coup d’état.

In your letter of resignation, you point out that the trials of the political prisoners are predetermined in the El Carmen presidential residence and that the Judicial Power has been practically eliminated. How are those trials conducted?

They have the characteristics of political trials because, independent of the crimes committed, they all took place within the framework of a political rebellion against the government. Political decisions are made there in El Carmen. What the judges do is to look at the facts in the file: if they have to do with a homicide that might have been committed, the obstruction of a public roadway, or all the classifications around the category of terrorism, and these are broad in the Penal Code. They then pass judgement without political considerations, because they’re limited to the legal area. But the possibilities are slight that a judge could rule against the accusation that the Prosecution is presenting in any of these cases, and say that there’s no support for the accusation and that the person is innocent. There have been some cases where the accused have gone free, where no proof has been presented.

And there’s even one where the defendant was declared not guilty but is still in jail: the case of Alex Vanegas.

There are some others who have gotten out, who were mostly irrelevant to the events that transpired, or, let’s say, there was no evidence to sustain the accusations. But, yes, I maintain that they’re political trials because they fall within that framework of the international criteria established to classify political trials.

How do you see the future of all these people who are being tried and condemned, while over three hundred murders remain unpunished? Are these trials going to continue, or could they be annulled?

In my opinion, they should be annulled. Although I didn’t put that expressly into the letter, I’ve said so in other interviews. I believe that they should be declared null and void, and a way should be sought to set the majority of these people – if not all – free, and to promote a true reconciliation in the country.

Obviously, I don’t see that really happening. It’s would be very difficult for the magistrates on the Appeals Court or the judges of the Penal Court to declare the trials annulled, or to revoke the guilty verdicts of the lower courts. It seems to me that this is going to have to wait for an agreement of a political nature, for there to be a political decision to declare the annulment of the trials and the release of all of the prisoners. Such a political agreement should be the product of a dialogue, as it would be very difficult for the Judicial Power to revoke the decisions that the judges have made in the case of the prison sentences.

The reports presented by the OAS Inter-American Commission for Human Rights and of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts regarding the repression and the deaths that occurred in these months, and which you cite in your letter, also state that they didn’t receive any collaboration from the government, nor were they allowed access to the legal files. How can the truth and justice of this massacre be established?

I believe that the first report that came out, the preliminary one, could have created the perception of a bias on the part of the government. Perhaps the Foreign Minister, the President, the Vice President and other people felt that they’d only considered the versions that they’d received from the human rights organizations. That’s why there was this closing of doors.

During the first meetings, to be honest, there was a large commission of us from different institutions with them, and yes, I felt that there existed the flexibility and the opportunity to review each case, on a case by case basis. An agreement was even signed to allow the integration of the Interdisciplinary Group of International Experts, the group that put out that very strong report this December.

It could be that the top government authorities felt there was already an established decision to attack them, and so they closed themselves off to giving more information.

The government expelled the three international human rights organizations: first the UN, then the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts, and later the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights as well. In Nicaragua, there are hundreds of families wondering – How can we find truth and justice in these killings, for these dead?

It’s obvious that this matter is pending. No in-depth investigation has been conducted to determine responsibilities, determine what happened. I believe that there was an excessive use of force. It could have been avoided from the beginning, it grieved many of us greatly, and I take advantage of this public opportunity to express to the mothers of so many dead Nicaraguans my deepest condolences and pain for the loss of their children.

There were also deaths in lesser numbers within the Police and of some members of the Frente, but it’s true that the majority came from the blue and white bloc [those who were protesting]. No in-depth investigation has been carried out.

It’s obvious that this is a matter that has to be dealt with by the National Dialogue, if resumed. It could also follow another path, that of international action, if the Commission later sends the case on to other instances of the United Nations, or of the OAS, or to the Inter-American Court. The Nicaraguan Penal Court is not a signatory of the International Penal Court, and as such they don’t have jurisdiction over it.

But the Inter-American Court of Human Rights does have jurisdiction.

Yes, and we’ve had a great number of cases in the Inter-American Court. Many cases are passed on from the [Human Rights] Commission to the Court. In other words, that’s a possibility that could occur in 2019. Nicaragua would then have to appear before the Inter-American Court, which by coincidence has its seat in San Jose [Costa Rica]. I agree with you that it’s an investigation that must be carried out. I don’t know if it should be handled by the same groups that have been in Nicaragua – by the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts, by the Inter-American Commission or by a group from the United Nations – or if a truth commission will have to be created, as has been done in other countries.

The Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts says that crimes against humanity have been committed and demands that President Ortega and the national Police authorities and other instances be investigated.

Yes, and at the hour that a truth commission is created – I don’t know if it would be national, international or mixed – the investigations would have to be carried out. We must take care not to begin with the end result. I believe that the Dialogue, if it begins, should include the original topics, but by this time you can’t ignore the topic of justice. It’s not only going to be about democratization, or about reconciliation, or about peace in Nicaragua, but it also has to touch on the topic of justice. It’s there that you must proceed to determining responsibilities.

In your letter you point out that President Ortega authorized arming with weapons of war the young people and retired Sandinistas who participated in the repression together with the police. These groups continue to be armed today, although according to the law there can’t be two armies in Nicaragua. Should the Nicaraguan Army disarm the paramilitary? Why haven’t they done so?

Yes, they should. And that’s the million-dollar question, because not only did I put that idea out now, when leaving the Frente, but there’s also a series of people who had previously proposed it: Humberto Ortega, Jaime Wheelock – who’ve been Sandinistas and even members of the Frente’s National Directorate – and other important figures within and outside the country have brought this up.

The Constitution establishes that the Army is the military body authorized to use war weapons. The other force that can also be armed is the Police, for situations of public order. But to go on from there and arm other groups was a barbarity. It was a mistake that could have provoked a civil war, if the others [the protestors] had been as well-armed; because they were armed, but not with weapons of the same nature as those held by the [paramilitary and police] forces who came to dislodge them [from the roadblocks].

However, the Army has maintained its neutrality. In general terms, I’d say that they’ve remained on the margins of the conflict, and they’ve made this public in several communiques. So, disarming the armed groups is a task that still pending.

In the arguments you offer at the end of your letter, you warn that President Ortega and Vice President Murillo could be leading the country down the road to civil war. Why?

That’s a warning that’s phrased a bit strongly, in order to try and trigger a discussion and a reflection on the need to resume the National Dialogue. No one wants war in Nicaragua. Nicaragua has had so many wars; war has been a cyclical event in the history of our country. No one wants it, not even those who are in the opposition groups speak of moving towards a situation of civil war.

I believe that if there’s no National Dialogue, and if it’s not resumed soon, in the coming weeks, and the economy continues deteriorating at an accelerated rate, the population could then begin expressing themselves violently in the streets, even though marches are prohibited. So, if last year’s repression should be repeated, we could arrive at a situation where people say: “Well, there’s nothing left here but the other route. If there’s no way out via the civic road, let’s look for a way to use the armed route.” That would bring the country to a civil war. That’s not something we’re seeing in the short term. Hopefully, God willing, it won’t happen, and they’ll manage to resume the Dialogue, because a war would end with the country’s destruction and no one wants that.

President Ortega has said that the country is going to enter a “subsistence economy” based on “gallopinto” [the national rice-and-beans dish]. Do you feel the same as other economic and business analysts that the economy is on the verge of collapse? Do the high government officials, the ministers of the economic area, share this concern over the economic situation, or do they believe that everything is going normally?

I think that there’s a perception that, indeed, not everything is normal from an economic point of view. I participated in bilateral talks with some members of the economic cabinet. Nevertheless, there’s not an accurate perception of the dimension of the economic crisis, or of what’s coming in the next months. Nor do I believe that they’ve made this felt to the President and the Vice President.

I think there are cabinet members who feel that the situation is manageable, that you can live with the situation by taking economic measures of one kind or another to confront the lack of direct foreign investment, the flight of capital out of the country, and a budget for 2019 that isn’t financed. They feel that by cutting back to a subsistence economy the country can continue to function without a catastrophe.

It’s something that could be argued, because there are others who tell you no, that obviously when tourism, construction, commerce and everything that has to do with the normal purchase of goods plummets, there’s going to be a strong reaction from the people themselves, apart from what it will mean in terms of unemployment and layoffs in the public sector and in the private one throughout 2019.

The main reason why you resigned is because Ortega and Murillo are not willing to seek a political solution. Under what circumstances do you think that Ortega would agree to negotiate? Is there any pressure that could force him to facilitate that step?

Right now I don’t see it [happening]. That’s why I resigned. Well, apart from the other reasons that I pointed out, of circumstances that occurred in these nine months that I didn’t agree with. I have the perception, to this day, still, that a will [to negotiate] does not exist.

If what is at stake is the future of Nicaragua, peace, reconciliation and reconstruction, can a political negotiation be conceived without Ortega and without Murillo? That’s to say, that after being separated from their positions, other figures of the regime facilitate a political negotiation?

Well, that would first mean a separation of them from their positions, which is something that is linked to the above. If they don’t want to go to a negotiation, much less are they considering their resignation, or a mechanism in which they are left out of a negotiation.

But if they can’t govern the country either, and there is a situation …

Well, that is something that remains to be seen, to what extent in the ranks of the Sandinista party there is that current, which I do not see either. I tell you sincerely, the resignations are going to be given one by one. I don’t see a future of mass resignations within the Front (FSLN) in the short term, or even in the medium term.

I think there is still a lot of fear to discuss these things within Sandinismo. Although the vast majority of the people, even within the Frente itself, want peace to return to the country and for there to be a National Dialogue, and even make concessions if you have to, so that the employment that has been lost by tens of thousands also returns. However, it is very difficult for you to say it within the party, because they may think that you’re bailing out, that you’re a traitor. The ability to discuss within the ranks of the Front at any level was lost a long time ago. The power is concentrated, and the decisions are only taken by the two of them.

How do you see the future of the FSLN if there is no political solution?

Bleak. It is obvious that, if there is no political solution, the Front itself will deteriorate in a very accelerated manner. The people in Nicaragua and Sandinistas themselves, their families, all Sandinistas, want this to be resolved. Although the polls still present you 70-30, more or less, the Front is still a strong party that has a base, and a national organization, throughout Nicaragua. But over time, if they feel that their leaders do not want a solution, they can become disillusioned and start leaving [the Party] in different ways. Some by public renunciation, others by way of not participating in activities, while some go into exile, or others stop voting, as was the [large] abstention in the last two elections. There are thousands of ways in which the message can be sent to Daniel and Rosario so that they sit down to a National Dialogue again and look for ways to stop this situation in Nicaragua, that’s what everybody wants.

How do you dismantle such a concentration of power? How can Nicaragua’s institutions be reconstructed?

That is going to be a process. Obviously, that will require a new Government and a Constituent Assembly to draft a new Constitution.

Do we have to reform everything?

I would go for a total reform rather than a partial reform, but this is a process that must be done throughout the State. It will require a lot of time and will also require a national agreement. It is not an easy task, but you have to start at the beginning, not at the end.

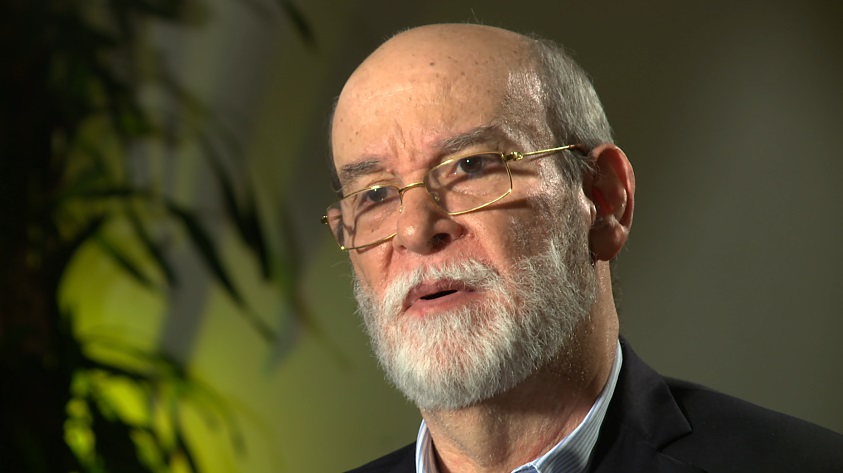

Rafael Solís resigned from his post as a Justice of the Nicaraguan Supreme Court as well as his militancy for over 40 years in the FSLN. Photo: Elmer Rivas | Confidencial

The indefinite reelection had its origin in the consecutive re-election, the Court ruled politically.

Regardless of your resignation and the reasons you have expressed about this political rupture, many sectors believe that you are one of those responsible for the design and consolidation of an institutional dictatorship that now led to a bloody dictatorship. What responsibilities do you assume?

I have said it clearly, I do assume my responsibilities, I don’t deny them. When the issue of re-election was raised that could be considered a big part of the problem, and the Court ruled that the article that had prohibited it was unconstitutional, we, and I personally did not see it as a bad thing.

It seemed to me that one term was limiting to an economic relationship with the private sector and to the growth of the country that had been taking place in the first five years [of the Ortega government], and that it was too little time to fulfill a government program, and that reelection was normal, as other countries have. We even looked at similar cases, although not continuous, but alternate, like the one in Costa Rica.

What no one foresaw was that after the constitutional reform was made, the Front (FSLN) would obtain an absolute majority of more than sixty percent, two thirds in the National Assembly, allowing for another constitutional reform that would allow indefinite re-election. But of course, the origin of the indefinite reelection was [the initial reform that allowed for] the reelection for a consecutive term.

Reelection is the core point of the enthronement in power and continuity of Commander Ortega.

Exactly.

But there was also the electoral fraud of 2008, the corruption of the Supreme Electoral Council, the law of the interoceanic canal that the Supreme Court denied its unconstitutionality, the lawsuits that have amassed in the Court, and the expulsion of the PLI deputies [from the National Assembly] in 2016. There is an accumulation of actions and responsibilities of the Court in the process of building this concentration of power.

That’s true, on political issues the Court ruled politically. On the strictly political issues there was that criterion. This Supreme Court must be seen over time. In 1990 it was totally changed, and a new Supreme Court emerged where only one of the magistrates of the FSLN remained after the negotiations. Later that was increased by two more, and then three. Then came the constitutional reforms, which led to that so-called Framework Law, and the number of justices rose to twelve. There the FSLN managed four, and eight were either Liberals or anti-Sandinista parties.

Then came the agreement with Alemán [and Ortega] and the court rose to sixteen justices. There were new magistrates, but the balance was still unfavorable in the political sense, therefore these rulings were political rulings. In many countries, when dealing with political matters, the judicial powers, depending on the origin [party loyalties] of their magistrates, also take into account these considerations at the time of issuing a ruling.

But this Court ended up in a monopoly of the FSLN, now directly subordinated to the person of Daniel Ortega.

In the end. But in its evolution, it was not that way, but it evolved from an anti-Sandinista Court, so to speak, for a period of almost fifteen years, to a Court effectively with a broad Sandinista majority, which guaranteed that on political issues judicial rulings were issued consistent with political decisions.

However, none of those situations could shed light on events that occurred after April 18th.

Before one would say, “Well, that’s fine, let’s say that the canal law was constitutional, or that in the case of the PLI, the group that is recognized is this, and the other group is not recognized.” But to foresee that in the middle of a national political agreement the government had with the private sector and with numerous unions, associations, and political organizations, that existed before April 18th, it was very difficult that the Court as such adopted another type of decisions.

This political Court, as you have described it, has also been identified as influence peddling, and there are magistrates who have also been accused of illicit enrichment, corruption, although there has never been an independent entity that could carry out an investigation. In your personal case, would you submit to an independent investigation?

Yes, yes I would. I believe that public opinion and the corresponding instances of the Government or of another nature, have the possibility of investigating the Court. We have been accused because a lot of lawyers also say: “I’m protected by such and such magistrate, and I did business with that magistrate.”

There has also been a lot of political backdrop in some of these accusations. However the scrutiny that can be done of the Judicial Power is something that covers past and present actions of all of us who have been magistrates. I think that as a public official, we are even subject to it, that is something that is open.

Does your resignation and your political break with the Government and the Sandinista Front imply any risk for you? Have you negotiated with any entity, a foreign government, any protection measure, in exchange for information?

No, not that. The decision was strictly personal. That is, the decision was made by me. I did not discuss it with any magistrate, with any member of my family. I felt it was time to do it. And I said: “That’s all for me” and I wrote the letter after arriving in San Jose [Costa Rica] and I sent it. You notice that there is a difference between the [date January] 8th, which was the day I wrote it, and the 10th, which was the day I sent it.

The Government of Costa Rica has welcomed me in a positive way, and I believe that it also obeys a tradition that Costa Rica has had regarding political asylum, although [thus far] I have not requested that possibility, I have not considered it. I am still within the ninety days of normal permission given by the Costa Rican authorities, and I entered by a normal route, from the airport, on January 7. However, it is a possibility that could occur. There are thousands of Nicaraguans here who have entered through other routes, not necessarily legal, who have refugee status and are living in this country.

But it is totally false that I negotiated in advance with the government of Costa Rica, as they say on some social networks, trying to dirty me, or with the government of the United States or with another government. There were no such negotiations. I felt that it was time now, to do it, because if I didn’t do it and I returned to Nicaragua, I was never going to do it and the country would continue on this same course, which was the wrong direction. And that’s why I said: “I have to do it, even if I have to stay in exile.”

Some top government and FSLN officials, like National Assembly deputy Jacinto Suarez and Foreign Minister Denis Moncada, have accused you of being a traitor. How do you respond to the grassroots members of the FSLN and to your ex-colleagues in the Government?

Those who know me, are aware that its not true. That it wasn’t a betrayal, there were no elements that could be considered betrayal. When you aren’t in agreement with something you can resign, even if they accuse you of being a traitor.

You saw Eden [Pastora] accused by Tomas [Borge] [back in 1982 when he left the government and formed a contra army] and later he rejoined the FSLN for many years now. Eden resigned for political reasons in that period, because he thought the Government was on an authoritarian course. However, later he returned [to the Party].

I was serious in the sense that I resigned from both the FSLN and the Supreme Court, and it makes no sense for me to join some other political group or party. It’s not in my personality either. I assume my responsibility and my history over the years. I have no interest in having space in opposition groups. This is a personal decision, with the hope that it would serve as an alert to see if the situation that Nicaragua is living could take another path.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D