29 de enero 2020

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Charles Call, international expert on matters of peace, speaks about the challenges that Nicaragua will face in the struggle against corruption

Charles Call

On Sunday, January 26, the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras, abbreviated as Maccih, concluded its four years of work. The government of Juan Orlando Hernandez refused to extend the mandate of this international commission of the OAS.

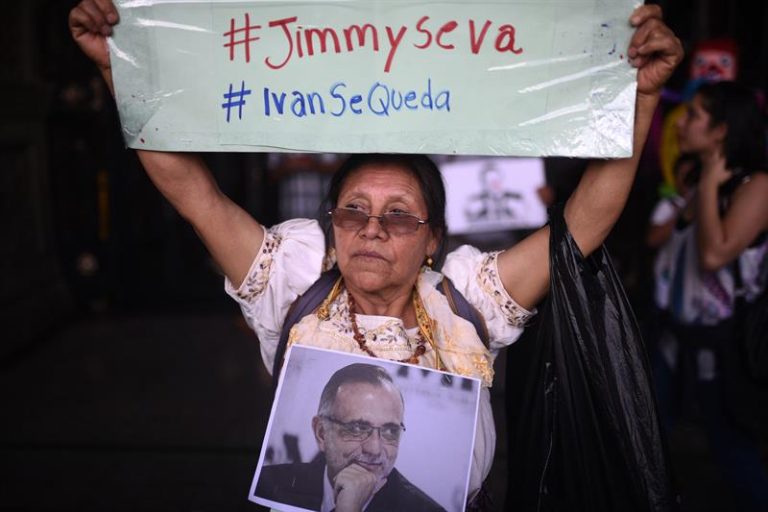

Similarly, four months ago the outgoing government of Jimmy Morales in Guatemala ended the United Nations International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (Cicig) after its 12 years of work, and declared its commissioner, Ivan Velazquez, persona non grata.

The balance sheet of the Cicig in Guatemala and the Maccih in Honduras have been the subject of analysis and public debate, especially in El Salvador where President Nayib Bukele has promoted an agreement with the OAS for assistance in creating an International Commission against Impunity in El Salvador (CCIES).

After the current regime in Nicaragua finally ends, what can the post-Ortega Nicaragua learn from these experiences in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador that will help them in the fight against impunity? What kind of international assistance might the country need in order to reconstruct the Attorney General’s office, reform the justice system and create a new National Police?

I asked these questions of Charles Call, a professor at the American University, and an international expert in the field of peace and conflict resolution, with vast experience in the Central American transitions. Call is the author of: “International Anti-Impunity Missions in Guatemala and Honduras: What Lessons for El Salvador?” In January of this year, he just published the working paper: “Too Much Success? The Legacy and Lessons of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala.”

The legacy of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala

The Cicig worked for over a decade in Guatemala, until last year when the commissioner, Ivan Velasquez, was declared persona non grata by the government of Jimmy Morales, who also cancelled the agreement with the United Nations. What did the Cicig bequeath Guatemala in terms of the fight against corruption and impunity?

During its twelve years of functioning, up until September of last year, the Cicig had a number of successes. In quantitative terms, it implicated 1,540 individuals in 120 filed cases. So, of these 120 cases there are more than 600 persons who are currently facing charges or another type of legal process. Two thirds of those tried were declared guilty, so in terms of numbers, that’s already a lot.

But the most important thing, I think was symbolic, the mission demonstrated to the Guatemalan population that any person in the country can be subject to the Rule of Law: ministers, members of the economic elite, elected officials. A president and vice president in power were forced to resign because they were under investigation, and both of them are detained. Other ex-presidents were investigated and tried. So this showed the people that it is possible to make the rule of law be applicable to everyone.

Ivan Velasquez, head of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, at a press conference at the site of the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Could the Guatemalan national institutions, the Guatemalan Attorney General, or the justice system, have carried out the investigations you’ve mentioned, without the Cicig?

No. Everyone concurs, that they’d never have been able to prosecute a president without the presence of an international mission. That’s not to say that they don’t have the technical capacity, but the presence of an international mission gave them the political backing and the coverage to be able to realize those investigations and bring them to Court.

Was the main objective and mandate of the Cicig to investigate impunity for the war crimes in Guatemala, or to combat the current corruption?

In fact, the mandate was neither of these. The mandate came out of a peace process and was to follow up on some illegal groups and bodies, and on the clandestine security apparatus. These illegal bodies had their origins in the military intelligence forces. They had hidden powers, and functioned as organs parallel to the state; during the war, they carried out actions of political violence linked to the counter insurgency.

However, when the war concluded, they began to transform themselves into criminal outfits. They became illegal bodies involved in robbery and corruption. The Cicig mandate was to focus on these groups, evaluating them and their relations, because they forged relations with civilians, with the democratization, with the peace process; they broadened their circle to the economic elite and also the political parties. So the Cicig was charged with analyzing these illegal groups and dismantling them, as well as proposing legal reforms to assure that they not reappear.

The criticisms that have been leveled against the Cicig, emphasize that it’s a body beyond the national scope. In the balance sheet you’ve published, you refer to this model as a hybrid institution. Did the Cicig allow Guatemala to strengthen its national institutions?

I believe so. Cicig began at the petition of the Guatemalan government, it wasn’t imposed by either the UN or the United States, nor by the donor countries. It was a strong support offered by the United States and other donor countries, but the mission itself stemmed from a government request and functioned under an international treaty.

It was a hybrid in the sense that it combined national and international authorities and capacities, and the cases were brought before the national courts, exclusively through the national prosecutors.

Some people say: “Look, this displaced the national capacity.” But in this case, the ones we spoke with in our study, including two of the nation’s general prosecutors, affirmed that it did greatly support the capabilities of the Public Prosecutor and of the Guatemalan Attorney General’s Office, as much through the training courses as through the joint work with very well trained international experts, who showed them how to do the things they didn’t know. In addition, they introduced them to some technical means that they could use: for example, the use of wiretapping was minimal before the presence of the Cicig, but when the Commission arrived, it became a much more prevalent practice in the Guatemalan Prosecutor’s office.

The Maccih in Honduras and the CCIES in El Salvador

In the case of Honduras, the mission against impunity (Maccih) was created under OAS auspices at the request of the Honduran government. However, its four-year duration was much shorter than that of the Cicig. What impact did the Maccih have in Honduras?

The success of the Maccih, like that of the Cicig, rests more on the creation of some special units that they accompanied in this fight against corruption. In both Guatemala and Honduras they established courtrooms that specialized in cases involving corruption or impunity. These had much better results than the normal courts in the two countries.

A specialized unit against impunity and corruption was also created in the two countries, and they’re still functioning right now. In Honduras, we’ll see what happens to it, but these were certified by the international missions as well as the prosecutors, for their credibility and their training – they were people whose hands were clean. So, these people were keys to the mission’s success.

The legacy of the Maccih is that it left some prosecutors who were much better trained. They only processed around a dozen penal cases in four years – ten times less that the Cicig – but these cases touched on some powerful people: one former first lady has already been sentenced to 58 years for her corrupt acts. Many deputies are under investigation, and some have already been processed in these cases. This also impacted the Honduran population by demonstrating that, yes, you can touch very powerful people. It didn’t reach as high a level as the Cicig, nor did it touch the economic elites in Honduras as it had touched them in Guatemala. The mandate was also more limited in Honduras, but a way was found to be able to accompany the national Honduran authorities.

Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele at a press conference. Photo: EFE

In El Salvador, a commission against impunity, the CICIES, is being born under an agreement with the OAS. However, it’s been questioned because it really lacks investigative faculties.

Yes, I agree with that. The novelty of the Cicig and the Maccih was that they had more teeth to participate in the investigations, and some authority. This gave them more power.

As far as the CICIES mission, the head of the mission stated in an interview in December that this is really technical advice, not a mission with power to carry out investigations. It can only provide technical assistance and advice. So, it’s not something outside what has existed in El Salvador since the eighties. The president wants to color it as if it were a Cicig [like in Guatemala], but really, it’s not.

Lessons for a post-Ortega Nicaragua

What can Nicaragua learn from the experiences of the Cicig and the Maccih? I’m not referring to the Ortega government, but to the post-Ortega Nicaragua, when there’ll be a demand to establish justice without corruption or impunity.

What would be important in a post-Ortega situation is that any process must adhere strictly to the law in carrying out its functions, and not be perceived as political vengeance. The lesson is that an international mission can lend more strength to efforts to end impunity; this has been the case in Guatemala and Honduras. It’s very possible that an international mission could help clarify things within a post-Ortega reality, so that the national authorities can realize sensitive investigations, with this warning: that it would have a negative impact if it were perceived as an instrument for political vengeance.

But in Nicaragua, all of the state institutions have collapsed. If an international entity with no investigative faculties were called upon to assist, how could a police force, a public prosecutor, and a total reform of the justice system be constructed at the same time? Can the two things be done simultaneously?

Yes, of course, that’s unusual. The only opportunities to study this kind of experiences are usually in post-war situations, where a war has ended and the UN or international donors come in, as in Haiti or in Panama, to reconstruct the national institutions, whose legitimacy – if not their capability – has been destroyed.

One of various lessons is the selection of relevant personnel, especially in the judicial function, because the judicial organ is independent of the Executive. It’s very difficult to have international personnel intervening in legal processes: in Courts decisions, for example, you don’t want that. Hence, the selection of the judges and their training are the most critical functions for these institutions. An international entity can aid in capacity-building, in legitimacy, a true legal process, by helping with the process of selecting judges.

Riot Police form a human fence around the San Miguel Archangel Church in Masaya in November of 2019. Photo: Carlos Herrera.

As far as the Police goes, that’s something else. Selection is also vital; one of the lessons is that [if you’re going to] to wipe out the police and put in new ones, it can be a good thing to include people who have experience despite having acquired it under the old regime. This is a very sensitive thing, because you don’t want to preserve the practices of politization, of excluding the police functions from the law. Nonetheless, you also don’t want, as happened in El Salvador, to erase everything and put in new people, when these new people don’t have the capacity, the experience, to be able to confront a wave of crime or delinquency as happens following political transitions.

In order to install an international entity in a future Nicaragua, be it with the collaboration of the UN or the OAS, would it require a national accord born out of an electoral mandate? Can a project of this type be sustained only by one sector or political party, or does it require a national agreement?

I sympathize with this position, because you don’t want it to be just one political actor that enters into an agreement with an international entity. On the other hand, though, it doesn’t require a national consensus. The most general way of affirming an agreement like this is through the approval of the legislative branch. It doesn’t require a one hundred percent consensus, it merely requires Congressional approval; in some countries, a qualified majority is required to ratify an international treaty, and in others it’s a simple majority.

There will always be enemies of an international mission. But you don’t want to give those corrupt people who might hold some vestiges of power a veto. On the other hand, you don’t want one political actor to be able to enter into such an agreement without any more general accord from the country’s important political factions.

Following the experience of the Cicig and the Maccih, would the international community be eventually inclined to support a new entity of this sort in the case of Nicaragua? The United States invested a lot of resources in Guatemala. Does the current government of Donald Trump have a commitment to this type of democratic reforms?

The experience in El Salvador and the experiences in Ecuador and other countries indicates that yes, these international institutions – the OAS as well as the UN and the donor countries – do have the disposition to support such an initiative.

Key to the Cicig and the Maccih initiatives were the government’s initial petitions. When there’s a petition from the government, these institutions generally want to help, and the experiences of the Cicig hasn’t damaged that disposition. However, they don’t want the mission head to have as much autonomy as the chief commissioner of the Cicig had; that figure was named by the [UN] Secretary General and no one else. The UN won’t want to enter into that sort of arrangement in the future. It is going to want it to be a more formal UN mission, like the OAS sponsored Maccih.

In terms of the United States, the Trump government isn’t generally in favor of multilateral mechanisms, but it’s been very much in support of the Maccih. But we don’t know what attitude the United States is going to have in the future. The only thing we do know is that their priority is immigration, and not the fight against corruption.

In the Nicaraguan crisis there are two topics at the center of the national concerns: one is the dismantling of the paramilitary groups and the mafias that are encrusted in power; the other is to effect justice for the crimes against humanity that have been documented by the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts. However, in today’s Nicaragua there isn’t a Special Prosecutor or a Justice system that could try them. Could an international entity take on those problems?

I believe so. There have been similar mechanisms in countries within other regions, such as Africa or the Middle East. What’s needed is the Government’s request and a mandate that is agreed upon with the international community.

As far as dismantling the paramilitary groups, this is more complicated than legal procedures against cases involving human rights, which is a more familiar field. There are few successful experiences in this. Generally, a new government that seeks to reestablish control and end the monopoly of violence in their territory and seeks to dismantle the paramilitary.

In the case of Colombia, there was an effort to demobilize the paramilitary, roughly from 2003 – 2006, with support from the OAS. Many criticize the fact that those groups weren’t sufficiently sanctioned, but these paramilitary groups did demobilize. There are some lessons there, that it’s possible.

Ortega “celebrates” together with his paramilitary in Masaya, while the Monimbo neighborhood is being attacked. Photo: Rodrigo Sura / Confidencial, EFE

In the experiences of Guatemala and Honduras, who were the principal allies of the Cicig and the Maccih against impunity?

First, in order to maintain their independence, these missions weren’t financed by the national governments. They depended exclusively on donations from other countries, and international bodies. Such support is vital. Second, in the two cases of Guatemala and Honduras the missions were created at the request of civil society. The support of civil society was vital for their genesis and also for their preservation. Perhaps in the case of Honduras, they would have survived a little longer with more support from civil society.

The corporate sector, in the beginning at least, didn’t veto the existence of these missions, and this was important in these cases. When the [Guatemalan] large business sector changed its position to oppose the Cicig, more or less about four years ago, that did complicate things, and abetted the mission’s termination.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D