21 de septiembre 2021

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

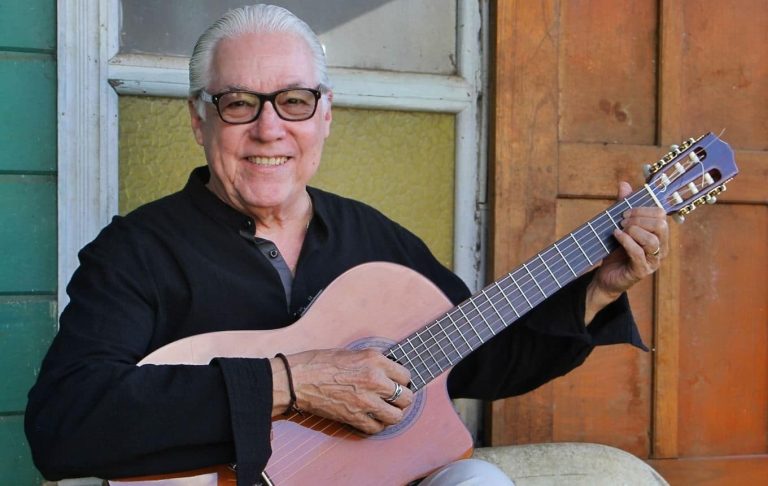

Legendary singer-songwriter Luis Mejia Godoy speaks about two very different epochs he spent in Costa Rica

Legendary singer-songwriter Luis Mejia Godoy speaks about two very different epochs he spent in Costa Rica

At age 22, a young man from Somoto, in northern Nicaragua, travelled to Costa Rica with plans to study medicine at the well known university of Costa Rica. It was 1967, a time when few Nicaraguans lived in the neighboring country, so much so that his classmates nicknamed him “the Nica”, because he was the only one they knew. He recalls the change he felt upon leaving Nicaragua under the dictatorship of Somoza, and coming to the serene Costa Rica, a democracy with conditions for making music, writing poetry, and growing culturally. That nagging “little worm” that had been inside him since he was a child was encouraged to grow.

It wasn’t long before the aspiring doctor was left behind and a musician was born. His experience as a migrant marked him in such a way that he turned his professional plans upside down, making way for his career as the fruitful and much-admired singer-songwriter, whose socially conscious songs have been enjoyed by a vast public. “The Nica” is Luis Enrique Mejia Godoy.

The artist tells us about his ties to Costa Rica and his experiences there. Today, he finds himself living in the country for a second time. This time, he arrived at the age of 74, in mid 2019. Once again, he left behind a country under a dictatorship.The citizens’ rebellion of April 2018 in Nicaragua enjoyed the artistic accompaniment and soundtrack it deserved. The Mejia Godoy brothers – Carlos and Luis Enrique – were on the frontlines, adding their voices and powerful lyrics to the historic moment. That greatly disgusted the Ortega Murillo regime, which then began to persecute them. That’s how the artist found himself once again in the land that had fostered his emergence as a musician. It’s his second homeland, he says. The first, of course, is Nicaragua, a land he claims as his own. Finally, he states, he has a third country: music. These are his three homes.

“Before, I traveled to Costa Rica a lot: three or four times yearly, as part of my foreign tours. Now Costa Rica is a place to live in, to survive in. It’s difficult, because this is a different Costa Rica from the one I lived in during the 70s.” Luis Enrique offered these comments in San Jose, the Costa Rican capital, where he now lives, and where he continues making music. He’s finding his way, despite the difficulties the pandemic has created for a performer who needs the applause and contact with his public.

Mejia Godoy shares his stories of that original migration amid laughter and thoughtful reflection. The nickname “the Nica” never bothered him, but it did make him uncomfortable to be told, “you don’t seem Nicaraguan”. He speaks of the ups and downs he had in his youth, when seeking work like all migrants. While dedicating his spare time to music, the young Mejia sold audio equipment, worked in a record shop and as a disk jockey at a discotheque. He was also a founder member of the National University of Costa Rica in Heredia, where he served as head of the Cultural Activities department.

The musician formed part of the popular Costa Rican band Los Rufos, which played cover songs of international Spanish-language hits. He also began to write his own songs for the group, together with the other group members.

The young singer-songwriter spent twelve intense years in Costa Rica, where he found his niche in protest songs that reflected social issues. “I began writing my first songs with social messages, not political ones. They spoke about the landlords, the abuse of the landless rural people,” he explains. Luis Enrique is considered a founder of the Costa Rican New Song Movement.

The era of social effervescence of the Vietnam War, the Cuban revolution, the movement that sought to defeat the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua, combined with the presence of exile groups in Costa Rica, nurtured the political vision of the young artist. He eventually became a committed member of the leftist party known as Vanguardia Popular, he adds.

During that time, he never lost his ties to Nicaragua. He travelled back and forth constantly to see his family. In one of those trips, he discovered the enormous coincidence that while he was in Costa Rica, falling in love with protest music, his brother Carlos Mejia Godoy, who had remained in Nicaragua, was also composing and singing political and social songs. This similarity would define the music of the two brothers for decades.

“From that moment on, I began to attend political activities with my brother Carlos. He had been invited by a group called Gradas (meaning Steps) to perform on the steps of churches, at demonstrations to free the political prisoners – at that time imprisoned members of the Sandinista Front,” Luis Enrique recounts. He notes the paradox in all this, since currently those who claim to represent the Sandinista Front are the ones holding political prisoners in the Nicaraguan jail cells. These political prisoners have also inspired both brothers’ recent songs of protest.

Back then, Luis Enrique had begun to sing about Nicaragua, and amid the wave of international solidarity towards the country suffering under a dictatorship, his songs began receiving widespread attention. In February 1979, five months before Somoza was defeated, his album Amando en Tiempo de Guerra [“Love in Wartime”] was released. “It was almost a premonition,” he says, “because then, what had seemed impossible, occurred.”

He was engulfed in the fervor to build a new Nicaragua, and made the decision to return to live there. First, though, he wanted to offer Costa Rica the farewell it deserved. “I did a tour called ‘Thank you, Costa Rica’. I said farewell with a huge concert in the National Theater with all my friends: the poets, the musicians, the theatrical performers. It was very emotional. That concert was titled ‘Volvere a mi Pueblo’ [‘I’ll return home’].”

After returning to Nicaragua in 1979 and living there for the next four decades, the singer-songwriter had to leave once again, unplanned. Initially, it was very difficult. Like every other migrant, he faced the hurdles of immigration paperwork in order to receive permission to work.

“I didn’t have a residency permit. I had to apply for permanent residency in the country in order to work. Even when I began working, I discovered a new difficulty: most of my repertory is original, or songs written by my brother Carlos. Either way, it’s all Nicaraguan material. I wondered: “Are the Costa Ricans interested in listening to a Nicaraguan talk, and - worse yet - one talking about problems?” he comments with a laugh.

Fortunately, he found there was a lot to harvest from what he had planted there during the decade of the seventies. He encountered warm acceptance from the Costa Rican public. They asked for his best-known songs, even some of the ones he wrote in Costa Rica so long ago - songs that capture some features of that country’s identity.

“I couldn’t believe that people knew my songs so well,” he remarks with pleasure. “I wrote Congoli Chango here. I wrote Zona Bananera (meaning ‘Banana-tree Zone’), dedicated to life in the Costa Rican region of Limon, on the Caribbean coast. I wrote a song called Muñeca, about an old lady who used to wander around downtown San Jose, and who everybody knew. My song ‘Poor Maria’, had its first success in Costa Rica, then became a rebound hit in Nicaragua – Can you imagine that?” he adds.

Now in his second stay in the country, he continues composing, painting and writing. During this era of pandemic lockdowns, he’s learned to present virtual concerts. A short while ago, he held his first in-person concert, following months of public health restrictions on mass gatherings. He even wrote a song about the COVID-19 quarantine called Tendra que florecer la Primavera (“Spring must bloom again”), which he recorded with a group of Costa Rican musicians. A music video of the song and its official release is coming soon, under the sponsorship of the San Jose city government.

“My brother Carlos says we’re like the birds that never retire, until God says, ‘Click. That’s as far as you go’”, Luis Enrique reflects.

“Pablo Antonio Cuadra said that Nicaraguans are in a permanent exodus for some reason, even just within Nicaragua. The earthquake displaces, a volcanic eruption displaces, a hurricane’s passing displaces,” that was the way the musician describes the way that migration marks the Nicaraguan identity.

It’s a harsh reality, he notes. “I think Nicaragua is one of the countries with the most emigration and the greatest number of dismembered families.”

Given this reality, he believes what’s important for migrants is to “earn their bread honestly, with their individual talent, conditions and capacities, and, above all, to maintain solidarity amongst ourselves. That’s very important. It’s a struggle, and the solidarity of the country you end up living in also has a big effect,” he says.

“Another important thing about exile and migration is that we Nicaraguans always want to return. It doesn’t matter how many years pass. We always keep our suitcases packed. That homesickness, that nostalgia for the homeland: you could call it either the homeland disease, or the homeland blessing, I don’t know which.”

Despite this, the singer-songwriter is convinced that now isn’t the time for him to go back. “While there are political prisoners, I believe that I shouldn’t return to Nicaragua. We can start there in enumerating the barriers: while there’s no freedom of expression; while they don’t return what they’ve stolen; until there’s a government that allows us to have justice done for everything that’s happened…” He continues the list: while the crisis and repression in Nicaragua only worsen in the advent of the scheduled November elections. These elections have been preceded by a wave of arrests and legal accusations against presidential aspiring candidates, opposition leaders, journalists, human rights advocates, business leaders and writers, sparked by Ortega-Murillo’s obsession to stay in power.

“I don’t want to set up false expectations for myself. I know we’ll be returning. Soon? I don’t know. I doubt it. How long will it take? I don’t know, but I can’t sit with folded arms,” Luis Enrique Mejia asserts. So, he continues creating, singing, making art for and about Nicaragua, about Costa Rica and social topics, about hope.

“There’s a beautiful stubbornness we Nicaraguans share,” he affirms. “To believe there can be a better future.” In this belief, of course, he’s no exception.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense desde 2007, con experiencia en prensa escrita, televisión y medios digitales. Tiene una especialización en producción audiovisual y una maestría en Medios de Comunicación, Estudios de Paz y Conflicto de la Universidad para la Paz de las Naciones Unidas. Fundadora y editora de Nicas Migrantes, proyecto por el cual ganó el Impact Award 2022 del Departamento de Estado de EE. UU. Ha realizado coberturas in situ en Los Ángeles (Estados Unidos), México, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua y Costa Rica. También ha colaborado con France 24, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, BBC World Service. Ha sido finalista y ganadora de varios premios nacionales e internacionales, entre ellos el Premio Latinoamericano de Periodismo de Investigación Javier Valdez, del Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS), 2022.

PUBLICIDAD 3D