20 de julio 2021

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

Like King Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, the presidential couple work together to betray a nation

Today's news report: a proposal for electoral reforms

One of the nine-member Sandinista directorate following the victory over Somoza in 1979, Daniel Ortega has followed a deliberate path to dictatorship. In 1990, when he conceded presidential victory to Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, pundits commented on how graciously and “democratically” he’d relinquished power. That may have been what it looked like. Now we can see how that moment and others have been part of a calculated design which included a pact with ultra-right forces, including the hierarchy of the Catholic church, to make Nicaragua his family fiefdom.

As a people, Nicaraguans are creative, courageous, and battle worn. They have struggled against the 19th century imposition of a US American as president of their country, a ruthless generational dictatorship, civil war, devasting hurricanes, volcanos, hunger, disease, and cultural appropriation. They were the only people in Latin America to expel the US Marines from their land. And in 1979, they gave us an example of a youthful and brilliant revolution that created a new society that inspired so many.

Thousands of activists in the international solidarity movement traveled to Nicaragua in the 1980s to participate in that extraordinary experiment. We found agrarian reform, newly taught near universal literacy, poetry, art, and widespread exuberance. We also saw evidence of the United States’ increasing attempts to destroy the young revolution, and weaknesses on the part of some Sandinista leaders that compounded those attempts. An opposition force, funded and trained by the US but drawing on homegrown dissatisfaction as well, was soon fighting the FSLN. The country descended into what was known as the Contra war, setting brothers and sisters against brothers and sisters.

I was one of many foreigners who went to Nicaragua during the early 1980s. I worked mainly in the area of culture. I marveled at Ernesto Cardenal’s network of poetry workshops—in factories and schools, on collective farms and in neighborhoods. I spoke with brilliant feminists determined to eradicate sexism in the public sphere and also doing their individual best to deal with it in their own lives. I was inspired by the innovative ways in which the Nicaraguan people turned their dreams into art.

I also worked for close to a year with the poet who chaired the Association of Sandinista Cultural Workers (ASTC). Her name was Rosario Murillo. In sharp contrast with most of the political leaders I knew, Murillo was a disturbing personality. I came to regard her as mentally ill. A competent poet, she was smart and creative. But she put her intelligence and creativity to Machiavellian use. I watched her humiliate co-workers, vilify those of whom she was jealous, and distort reality until I could no longer bear to be in her presence.

Like so many, I was blind to Ortega’s and Murillo’s deviousness. Most of the Sandinista leaders were honest men and women, creating a new society at great personal sacrifice. Many conservatives and even some members of today’s Blue and White movement for Nicaraguan democracy have accused those of us who supported the Sandinista revolution in its early years of having been fooled into a sort of acritical belief in the Sandinistas of the 1970s and 1980s. Untrue. Speaking for myself, I was exuberant but also questioning. After all, I had lived the previous decade in Cuba and had witnessed firsthand that revolution’s errors as well as its magnificent achievements. I knew that revolutions are made by humans of all stripes.

I remember that Daniel Ortega’s stepdaughter, Zoilamerica, was in a female militia battalion with my youngest daughter, Ana. In those difficult years, young as well as older people were being trained to defend their country. Another mother and I noticed a discomfort on Zoilamerica’s part. Something about the young woman wasn’t right. We wondered if she might be facing problems at home. We couldn’t have imagined that she was being victimized by her stepfather with her mother’s tacit permission. We didn’t have the words for that kind of abuse back then. Now, so many years later, I realize what we were seeing. But what could we have done at the time?

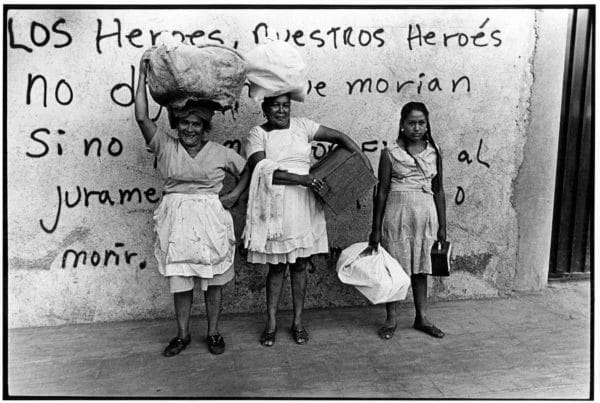

“Women with wash in front of a wall with lines from a Lionel Rugama poem, Tipitapa, 1979.”

I am proud of having given my all to that and other projects of social change. I continue to revere those men and women who exchanged comfortable lives for love of country and collective creation of future. I also know how important it is to the possibility of ongoing change that we tell it as we see it. This means being willing to analyze information as it becomes available. It means having the courage to speak out, not just about some of the failures but about all of them.

In 1998 Zoilamerica held a press conference at which she denounced the fact that her stepfather had raped her for nineteen years beginning when she was eleven. He responded to her resistance by telling her it was her “revolutionary duty” to satisfy his needs. Needless to say, Ortega denied her charges. And Murillo abandoned her daughter in defense of her husband. This isn’t that unusual in such cases. Many mothers, economically dependent on their spouses, take the man’s side. Murillo did so out of her voracious quest for power.

Ortega and Murillo contested and shaped the narrative of his abuse to suit their political needs. He went so far as to tell the Nicaraguan people that his wife wanted to apologize to the nation for having given birth to a treasonous daughter. Zoilamerica then courageously tried to bring her stepfather to court. In a country where the entire legal system was against her, her efforts were unsuccessful. The wounds of sexual abuse never heal. She now lives in another country. She recently described how she finally realized that Rosario Murillo gave up being her mother the day she sided publicly with her abuser.

There are those in the historic solidarity movement as well as in today’s Blue and White movement who resist mentioning Ortega’s incest. They say it is “a private matter.” They don’t believe the crime of long-term sexual abuse compares with the more public crimes of violation o civic norms: getting rich by stealing public funds, making draconian laws to justify eradicating all opposition, unilaterally changing the Constitution so as to be able to be president for life, or kidnapping, imprisoning, torturing and exiling thousands of citizens of all ages, degrees of involvement and oppositional impact.

Some of these members of the solidarity community even call themselves feminists. They dishonor the term. They also display a lack of understanding about power itself. Ortega and Murillo’s betrayal of Nicaragua is simply another type of crime, involving the same betrayal of power. No matter how uncomfortable it may make some to talk about the issue, what the duo has done to their daughter cannot be separated from what it has done to the nation as a whole.

I am reminded of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the archetypal drama about a fearful but power-hungry king and his wife, Lady Macbeth, with all her ambition, strength of will, cruelty and dissimulation. In the western world and for several centuries, those protagonists have exemplified a certain sort of royal malevolence. Perhaps Ortega and Murillo are present day archetypes of this evil. Each needs the other, and as a woman, Murillo especially has opted for achieving power through her allegiance to her husband. Like Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, the couple works in tandem to betray a nation.

Archetypes represent groups. This is why they are called archetypes. Ortega and Murillo are examples of one-time revolutionaries who hide behind their rhetoric as they abandon service to achieve personal gain. They are tragic archetypes for a new age.

***

Margaret Randall’s books on Nicaragua are: Doris Tijerino: Inside the Nicaraguan Revolution, Sandino’s Daughters, Risking a Somersault in the Air, Christians in the Nicaraguan Revolution, and Sandino’s Daughters Revisited. Her 2020 memoir, I Never Left Home: Poet, Feminist, Revolutionary, includes a chapter on her time in Nicaragua.

This article was originally published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

PUBLICIDAD 3D