13 de febrero 2021

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

“The new administration will accompany the individual sanctions with other strategies. However, “the ball is in Nicaragua’s court.”

Según la VOA

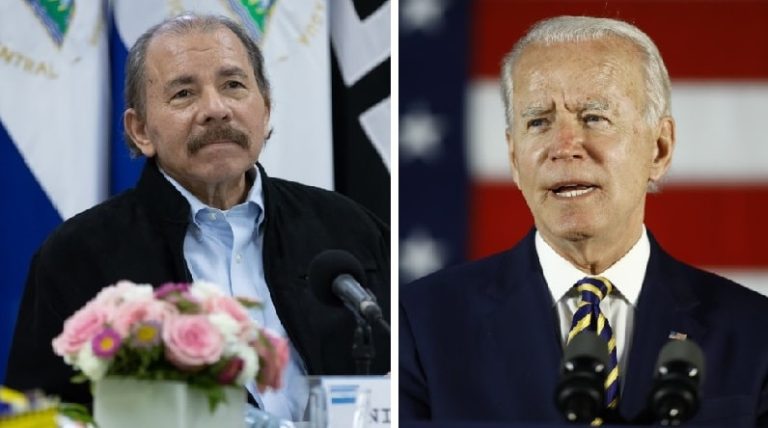

Daniel Ortega’s hopes of a softer US foreign policy towards Nicaragua were dampened by a recent press release. The statement, released February 8th by the US State Department, accused the Ortega regime of leading Nicaragua towards “dictatorship”.

Mateo Jarquin, historian and professor at Chapman College, researches US- Latin American relations. To him, the statement had one key message. “No one in the Biden Administration nor in Washington doubts the authoritarian nature of the Nicaraguan government.”

Mateo Jarquin appeared in a February 10th interview, broadcast on the internet television news program Esta Noche. He emphasized: “there’s total bipartisan support in the US Congress for the policy of sanctions.”

From 2018 to the present, the US has sanctioned 24 high-level functionaries of the Nicaraguan government. They include Rosario Murillo, Nicaragua’s vice president and first lady, and three of the presidential couple’s sons: Laureano, Rafael and Juan Carlos.

What’s your reading of this statement about the Ortega regime from the US State Department? It’s their first declaration since Joe Biden assumed office.

More than anything else, it signals continuity. In the press release, Tony Blinken [new US Secretary of State] states that Ortega is leading the country towards dictatorship. What we perceive in that phrase is a certain unease within the Biden administration with the former “policy of extreme pressure”. That’s the policy the outgoing administration implemented in Iran, Venezuela, Cuba.

Nonetheless, there’s no reason to believe that the sanctions leveled on Nicaragua are going to be revoked. No one in the Biden administration, nor in Washington, doubts the authoritarian nature of the Nicaraguan government.

The choice of language – telling Ortega that he’s leading the country towards dictatorship. Does it in any way suggest an opening towards the regime?

I don’t know if the term “opening” is the most appropriate. I believe it does show evidence of greater flexibility. At the least, it represents the new administration’s conviction that individual sanctions must be accompanied by other strategies. Possibly, some strategies that are a little more realistic for achieving a democratic opening in the region.

In that sense, I think the press release on Nicaragua reflects the general changes that we’re going to see. We’ll be seeing these general changes in United States policies towards Latin America under the new regime.

The press release clearly notes that there’s repression and human rights violations in Nicaragua, with no perspective for free elections. That’s not good news for Nicaragua.

Administrations change, figures change, maybe the rhetoric changes. Nonetheless, Ortega has to understand that there’s total, bipartisan support for the policy of sanctions within the US Congress.

Do you think this State Department message surprised Ortega? Was he hoping for some rapprochement on the part of Democrats? During the 80s, some personalities who are today very influential opposed the Republican policy of backing the Contra.

To clarify – in the 80s, there wasn’t really much sympathy within the Democratic party for the Sandinista government’s revolutionary project. There were a few exceptions, notably Senator Bernie Sanders. What there was, above all, was opposition to the Reagan government’s policy of intervention.

Today in Latin America, there’ll be new diplomacy on the part of Biden’s team. They’re going to have less tendency to act unilaterally in the region. I expect less emphasis on sanctions and pressure tactics to effect changes in the region. They’re going to be a little more flexible, in general. They’re going to look for different tools to go along with the pressure tactics.

Speaking of Congress, there’s a new bipartisan initiative from Senators Ben Cardin and Roger Wicker. They propose broadening the reach of the sanctions leveled under the Global Magnitsky Law. They’d like it extended to the direct family members of those sanctioned for human rights violations and corruption. What are the possibilities of this bill becoming law?

It seems very probable. I believe it forms part of a broader tendency. In the US as well as the EU and Canada, there’s greater appetite for broadening the use of individual sanctions. They want to extend the use of this tool in countries that are in the process of undermining democracy. There will, in fact, be changes in Central American policy under Biden. However, these are going to be felt much more in the countries of the northern triangle than in Nicaragua.

Nayib Bukele, president of El Salvador, recently visited Washington. However, none of the important officials in the Biden administration wanted to meet with him. Meanwhile, spokespersons for the Biden administration are emphasizing the topic of combatting corruption in Guatemala and Honduras. Does this signify a change, compared with the Trump administration?

Yes. People in Latin America can expect to see two fundamental changes from the Biden administration. One is a shift back to multilateralism, whereas the outgoing administration emphasized unilateral and bilateral strategies. The other change is more emphasis on building stable institutions in Latin America. That means focusing on democratic institutions, human rights, the topic of corruption. Obviously, this was something that the Trump Administration had stopped paying attention to.

What does that mean for Central America? [Honduran president] Juan Orlando Hernandez, for example, whose family has been implicated in drug trafficking, will feel a difference. He’s going to have a more uncomfortable relationship with the Biden administration. The government of Bukele is also going to have slightly more uncomfortable relations. His authoritarian tactics have raised concern in the US and Europe.

But although the emphasis changes, the fundamental interests of the US in the region aren’t going to change. They’re still going to emphasize the geopolitical competition with China, developing trade relations, managing the Venezuelan crisis. Above all – and this is the most relevant thing for Central America – they’re interested in controlling the flow of migrants towards the United States.

During the electoral campaign, the Democrats announced they’d be effecting changes in Trump’s policies towards Cuba. Do we know what these changes are?

Tony Blinken played a very important role in the Obama administration’s process of normalizing relations with Cuba. It’s to be expected that the new administration will resume that path. This policy of normalization is based on two key ideas.

One: that five decades of sanctions and blockade in Cuba have failed to produce regime change. Nor has it produced a democratic opening in Cuba. Two: that the policy of isolating Cuba has generated a lot of friction in the Latin American region. Again, changes in US policy towards Cuba will reflect a Latin American strategy based on more multilateralism.

President Trump’s strategy put Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela all in the same bag, the so-called “Troika of tyranny”. Will that notion continue under this administration, or will we see policies that differentiate between the three countries?

We won’t be seeing that discourse on the “Troika of tyranny”. The Trump administration’s policy was based on an electoral logic that is no longer relevant. To the Republican party, the Cuban and Venezuelan emigrants in South Florida represent a very important political base. This new administration no longer has that base, so they won’t emphasize policies based on that electoral incentive.

What does this mean for Nicaragua? The Biden plan for Central America doesn’t even mention Nicaragua. The $4 billion dollar package is aimed at attacking the roots of migration from the Northern Triangle to the US. Those roots, as we know, are violence and corruption. The Biden plan is really a continuity of the Trump and Obama administrations. In both, controlling migration has been the fundamental interest of the United States in Central America.

In Nicaragua, when we think about the international sociopolitical crisis, Venezuela immediately comes to mind. However, we should understand that the United States and a good part of the international community look at it differently. They see it through the Central American lens of insecurity and migration.

Does the Biden administration have the tools to pressure for a political way out in Nicaragua? Either directly through the OAS or through the opposition?

They’re going to make a greater effort to work through the OAS and the inter-American community. But we have to understand that the impact of international policy on Nicaragua, depends on what’s happening inside Nicaragua. The possibility that the EU or the US could produce a change is very limited. They can’t immediately resolve the problem of weak institutions in Nicaragua, or the problem of a divided opposition.

I expect a greater emphasis on denouncing the undermining of democracy and violations of human rights. But the international community has a relatively limited scope of influence. The outcome depends on the Nicaraguans.

In other words, the ball is in the Nicaraguans’ court – the court of the opposition, of civil society. It’s up to them to confront this crisis caused by the police state and the lack of electoral reforms.

Definitely it’s in Nicaragua’s home court. I really believe that the role of US foreign policy in the day-to-day isn’t going to change. They understand the need for a unified opposition, and they’re going to continue promoting it.

Archivado como:

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Confidencial es un diario digital nicaragüense, de formato multimedia, fundado por Carlos F. Chamorro en junio de 1996.

PUBLICIDAD 3D