6 de noviembre 2024

Children of Exile: The Births “Sowing Hope” in the Camp of Nicaraguan Farmers

PUBLICIDAD 1M

PUBLICIDAD 4D

PUBLICIDAD 5D

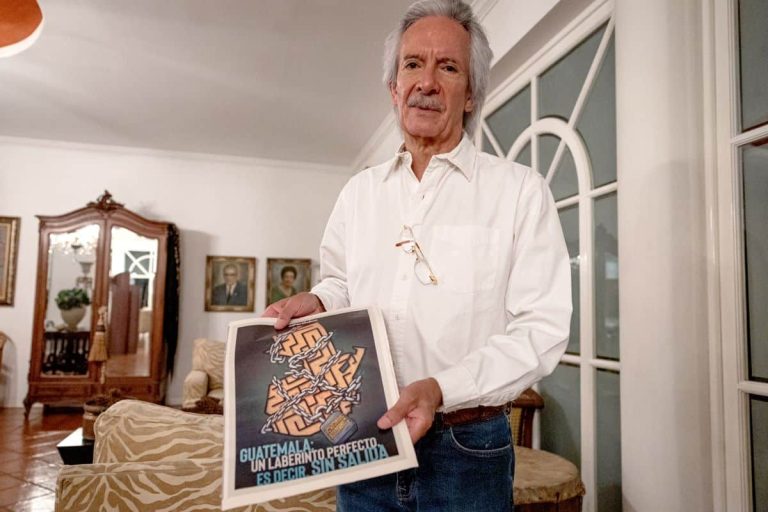

"My arbitrary detention exposed the corrupt dictatorship in Guatemala, which we had been trying to show for 30 years at my newspaper ‘ElPeriodico”

Jose Ruben Zamora, industrial engineer, journalist, businessman, and pioneer of the modernization of the independent press in Guatemala and Central America, is back home. The house he returned to is still empty following his family’s choice to go into exile. He says he’s lived his first two weeks in conditional freedom “with great intensity, overwhelmed and grateful for the solidarity, and still without time to rationally absorb my new normality.” Zamora spent 813 days in a cell in the isolation wing of Guatemala’s “Mariscal Zavala” jail.

The Attorney General’s office headed by Consuelo Porras, the iron lady of Guatemala’s “pact of the corrupt,” accused Zamora of “asset laundering and obstruction of justice.” The implacable political persecution he’d been the object of culminated in the forced closure of ElPeriodico, the media outlet he founded 26 years ago, after having led Siglo 21, another emblematic media outlet, during the Guatemalan political transition at the beginning of the 90s.

His imprisonment also brought him large economic losses and debt, not to mention the exile of his wife and children, to avoid being criminalized themselves. It also caused visible physical and emotional scars. He recalls the metallic sound of the solitary cell door closing, the constant vigilance and nightly searches of the guards during his first days in prison and the furtive invasion for months of hundreds of worms and insects, whose bites made bloody welts everywhere.

Nonetheless, Zamora also describes his “isolation and solitude as an indispensable contribution to a greater cause. My arbitrary detention exposed better than ever the fascist regime and the dictatorship of corruption in Guatemala, something we at ElPeriodico had been trying to show for 30 years.” That was the summary of this journalist who in 2024 was awarded the Gabo prize in Recognition of Excellence.

In this interview for the weekly news program Esta Semana – transmitted via the Confidencial YouTube channel due to the ongoing television censorship in Nicaragua – Zamora outlined the legal battle he continues waging to regain his innocence. He also analyzed the political crisis current Guatemalan President Bernardo Arevalo, himself under constant harassment from the Attorney General’s office, is facing. Finally, Zamora spoke about the future of journalism in Guatemala: “Although my arbitrary detention was a direct attack on press freedom and a message intended to terrify journalists, it’s encouraging to see that they continued their efforts despite the climate of fear and repression.”

How did you survive those 813 days in a solitary prison cell?

With humility, patience and faith. Learning to be happy with that was within my reach and with the conviction that my isolation and solitude was an indispensable contribution to a greater cause.

It exposed our political systems and showed they are variations of fascist dictatorships at the service of the Narcos, corruption and impunity.

My arbitrary detention exposed better than ever the fascist regime and the dictatorship of corruption in Guatemala, something that we at ElPeriodico had been trying to show for 30 years.

What impact has this persecution of independent journalism had on Guatemalan society and Central America?

The most relevant thing is that it revealed the abuses of power in Guatemala and brought worldwide attention to the country. Citizens, journalists, and free and democratic nations demand respect for freedom, democracy and justice. Although my arbitrary arrest was a direct attack on press freedom and a message of terror to journalists, it is encouraging to see that they continued their work despite the climate of fear and repression. They continued denouncing corruption and the abuse of power, showing more collaboration and solidarity in our profession than ever before.

You have now spent two weeks at home on conditional liberty, a type of house arrest. How have you experienced these days?

With great intensity. Ever since I entered the house, there’ve been a large number of visitors, neighbors who have come with great respect to leave me carnations, food, a thousand courtesies and kindnesses. I don’t know them, but they’ve manifested great joy at seeing me out of jail. I’ve had days when five or six different groups of people come to see how I am. I haven’t had time to be able to rationally process my new normal. When I’ve had to go out to do some business at the Public Prosecutor’s Office, or I’ve gone to a coffee shop, or gone out to walk my ten kilometers a day, people stop me, ask me for a hug as if I were a hugely important figure. That has me a little overwhelmed and scared – it’s not something that normally happens to us journalists. But I have to be grateful and learn to live with it.

When you were detained over two years ago, there were already a lot of signals that the Attorney General’s office had made the decision to begin legal actions against you. Could you have chosen exile at that point to avoid arrest?

The witch-hunt became more dangerous and risky during the final seven months [before his arrest]. I went to Miami to have 47% of the meniscus extracted from my knee. There, I received a message from an informant, saying: “Señor Engineer, good evening. I want you to read the following screenshot.” The screen he forwarded said: “We’re going to put the screws to Zamora. We’re heading to look for an inevitable finding.” I understood what that was about, and that the following Monday a concept would take place that I had no notion had ever existed, which is a “unilateral hearing.” An audience involving only a judge, at the request of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, in which the person supposedly accused of having committed some crime doesn’t participate.

That next Monday, I returned [to Guatemala], and ElPeriodico blasted the news on the first page that a criminal persecution had been initiated, to take place at 9 a.m. that day. They then cancelled it, and that’s where it all began.

For about seven months, Monday through Friday, I’d been sending my lawyers to various agencies of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, asking if there was anything we needed to dispel, or anything to clarify. At first, they wanted to get me for a case that had been filed and abandoned in 2013, in which the ones they were actually pursuing were some Social Security executives who had nothing to do with my case. Then, in January, they went after me for having published an “effective collaboration” which made it evident how the corruption mechanisms functioned in the Attorney General’s office. That “effective collaboration” was leaked, and I published it. So, they wanted to take me away for having done that, as well as for publishing the contract for the purchase of Russian vaccines, a deal arranged via a confidential contract between the State of Guatemala and the Russians, something that is theoretically illegal.

I had continuous calls from people saying: “Hey, they’re coming for you today, and it’s urgent that you leave for El Salvador. We can take you in a convoy of Suburbans.” They offered this possibility the day before they came to arrest me. But I believed, and I’m still convinced, that I must be here, to show my face, and establish that anything they ask me has an explanation. I never thought of leaving.

They accused you of asset laundering and obstruction of justice. Two years later, you’ve had several hearings as part of this legal process. Has the Prosecution presented any valid evidence?

I’m going to share the ruling that was suspended from the tribunal before they accused me. Their conclusion, read by the presiding judge, stated: “The Public Prosecutor’s office has been unable to prove that the origin of the money was illicit. However, Jose Ruben Zamora was also unable to demonstrate that the money was licit.” I must tell you that the burden of proof belonged to the Prosecutor’s office, not to me. They couldn’t prove that it had any illicit origin.

Despite that interchange of proof you’re pointing out, the accusation against you remains standing. Do you trust the mechanisms for justice in Guatemala?

I was acquitted of influence peddling. I was acquitted of blackmail. They presented an individual who declared that in 1994, I published an interview about irregularities in a state bank. That it was two pages long, and on a third page the bank manager categorically states: when we became aware of the irregularities that were real, we started to address those problems, and we resolved them.

Next, an individual was presented as a witness who said that he made a complaint with me that never went forward, but it wasn’t for blackmail, but for religious discrimination nothing to do with blackmail.

The most important part was what the judge told the prosecutor at the end, explaining to her why a charge of influence peddling was impossible. And as for blackmail, she told her: “look, you accused Zamora of blackmail between July 16, 2022 and July 28, 2022, but you are bringing me witnesses that not only aren’t talking about blackmail, but are from events that occurred between eight and twenty years before. There is no blackmail.” And as for the money, she told the prosecutor: “you failed to prove that it was money laundering.”

They wanted to give me a total of 116 years – 20 years for eight opinion columns I wrote criticizing the Attorney General. Then they wanted another 20 years for aggravating circumstances, and another 20 years for abuse of power. Abuse of power is something you can only accuse public officials of, not journalists or the rest of society.

The Attorney General’s office alleges that they’re not going after you as a journalist, but as a businessman, or for a different type of actions. However, you’re describing accusations based on publications in the news media. Who’s behind these accusations from the Attorney General’s office, and what’s the deeper motive of this persecution or this accusation?

We printed some 210 different journalistic investigations on [former Guatemalan president] Giammattei and some opinion columns about him and his companion.

The prosecutor expelled Juan Francisco Sandoval [Special Prosecutor against Impunity] from Guatemala and sent him running for the border, and I criticized her very severely. It was a firing that resulted from an illegal persecution. Later came the election of the Attorney General, in which she was reelected through a process full of coercion and threats.

So they had to elect the woman, and they included her among the six candidates that were then to pass to the President for the final selection. And they, after voting, they gave the reasons for their vote, but that entire election was irregular, and I pointed this out in a report and also expressed it as my personal opinion.

What’s been the impact on El Periodico, the news site you direct, of this persecution and imprisonment?

They eliminated 200 jobs of 200 colleagues. They destroyed our patrimony. My accounts are still seized. I can’t respond to the banks that are expecting me to honor the money they lent me prior to the pandemic.

ElPeriodico wasn’t in debt, we had to go into debt to survive the pandemic, but we almost had all our financial commitments covered. However, now these debts have grown and the accounts of ElPeriodico are also still frozen. That added greatly to the difficulties for the few months after I ended up in jail. I still have some of those creditors pending.

Your imprisonment galvanized the press in Guatemala, in Latin America, in the world, who saw it as a symbol of press resistance in the struggle against power. Can Guatemala’s independent press continue investigating corruption and abuses of power today?

It’s complicated. The country has been on a roller coaster, with periods of great freedom. The journalists themselves and each and every media outlet are pushing to expand the frontiers.

Now we’re in a moment where it’s possible to put out some journalistic publication based on facts about corruption and depending on who you’re talking about, they can take you to jail. There’s justifiable fears and a lot of carefulness to see which things are essential to publish. People are afraid.

In Guatemala, there are a number of journalists and also former functionaries of the Justice Department in exile. Can they return to the country?

While the Attorney General remains in power, they can’t return to Guatemala. It’s impossible. This will have to wait, since there’s still something like a year and five months before she leaves office. During that time, they can come, but they’ll face arbitrary legal accusations, and face violations of their rights, that they run all over them and that they have to go to prison, and be left isolated and incommunicado.

This article was published in Spanish in Confidencial and translated by Havana Times. To get the most relevant news from our English coverage delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to The Dispatch.

PUBLICIDAD 3M

Periodista nicaragüense, exiliado en Costa Rica. Fundador y director de Confidencial y Esta Semana. Miembro del Consejo Rector de la Fundación Gabo. Ha sido Knight Fellow en la Universidad de Stanford (1997-1998) y profesor visitante en la Maestría de Periodismo de la Universidad de Berkeley, California (1998-1999). En mayo 2009, obtuvo el Premio a la Libertad de Expresión en Iberoamérica, de Casa América Cataluña (España). En octubre de 2010 recibió el Premio Maria Moors Cabot de la Escuela de Periodismo de la Universidad de Columbia en Nueva York. En 2021 obtuvo el Premio Ortega y Gasset por su trayectoria periodística.

PUBLICIDAD 3D